Corporations in the Consulting Room

What do we stand for, and what stands in our way?

By Linda MichaelsIllustrations by Austin Hughes

Thinking back to the early days of the pandemic, I remember the pervasive fears of death, contamination by the other, the lack of ICU beds and ventilators. Not knowing better, we wore bandanas, cleaned our mail, excessively laundered our clothes, and banged pots out the window at 8 p.m. each night. With time, we learned to don N95 masks, social distance, and take the vaccine.

One thing that didn’t require waiting was the switch to teletherapy. After New York locked down and lockdown was imminent in Chicago, where I live, I went to my office on a Sunday, picked up my plants, packed a few beloved books as my transitional objects, and started seeing my regular schedule of patients Monday morning on my computer at the dining room table. Online therapy options were, quite literally, a lifesaver. I didn’t skip a beat or miss a session with a patient, and at least that regular rhythm of our work was spared from the long list of losses inflicted by the pandemic.

Therapists did have reservations about seeing patients online, wondering how the mediating technology would impact the relationship, the transference, and the ability to connect emotionally. But telehealth technology was also hailed as a new form of access to care for marginalized and disenfranchised communities. Although telehealth options had been around for decades, finally this widespread adoption of teletherapy would open up access to rural communities and those who couldn’t afford to travel to therapists’ offices, whether due to lack of funds or inability to take time off work or more debilitating fears of leaving the house.

What a shock to learn that the shift to teletherapy has done nothing to move the needle on access. If anything, it’s reinforced existing disparities. Online therapy has mainly offered one more option or convenience for wealthy, white, educated, employed individuals to access therapy. Low-income families, people of color, and adults in serious distress did not benefit. Sadly, as published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, “during the years of the pandemic, the use of mental health services by Black children and adolescents decreased … In the same period, the use of mental health care among white children rose.”

Private Equity Playbook

What happened? How did this technology solution fail so many so profoundly? While there are likely many ways to approach this question, one is to look at the companies providing the technology and selling the “teletherapy solutions.” We can look at their business models and their corporate values. In my estimation, it’s these corporate values that derive from profit-seeking motives that are most significant—driving growth for these companies at the expense of access and quality care, and in direct opposition to many important psychoanalytic values (spelled out below).

Regarding business models, technology and software developers are often financed by private equity and venture capital funds. Private equity and venture capital investors seek out industries, companies, or a constellation of market conditions where they can make money—and not just money from selling their products and services, but exponentially more money from buying and selling companies. During the pandemic, the imbalance between supply and demand in mental health care—low supply of therapists at a time of high demand for therapy—caught the attention of the financiers. They had previously been making profitable inroads into medical/surgical health care, buying up outpatient surgical sites, MRI centers, and physician practices. They then turned their attention to mental health, buoyed by the supply/demand imbalance and the presence of government and insurance monies that paid for therapy—an exploitation of the parity law and the Affordable Care Act’s inclusion of mental health care that we so often applaud. Where we hoped for improved access and greater equity, these companies saw an opportunity to put their playbook into action.

The classic private equity playbook entails buying distressed companies or individual companies, often in a fragmented industry, and combining them to gain economies of scale. Then the new owners amplify profits by reducing costs and increasing revenues. Cost reductions are often achieved by laying off workers, increasing workloads, limiting benefits or training opportunities, and reducing compensation (despite initial promises not to). Increased revenues come from investing in marketing to sell more. They load up the companies with debt to finance these activities, and then sell the entire investment off to another owner within 5–7 years. Then, like sharks that never rest, they move onto another target company, rinse and repeat.

Instead of feeling like an extended family where therapists felt proud to work, the therapists wait in fear of the next memo outlining a pay cut, benefit reduction, or demand for higher productivity. The spirit, the culture, and the values of the original small group practice have been crushed.

These new entrants have not only supplied the technology platforms for conducting online therapy, but they have introduced new products/services for consumers, for businesses, and for therapists themselves. New consumer products include apps to find therapists, treat symptoms (self-help guides and exercises), learn skills (mindfulness, meditation), and even bypass therapy altogether with substitutes (coaching, wellness). The global market for mental health apps was valued at $7.4 billion in 2024, and is projected to continue to grow. Notably, these apps mainly target the worried well, not to mention those who can afford to pay. Those with serious emotional or psychological problems and those from under-resourced or marginalized communities continue to be left further behind. Traditional psychoanalysis has also been criticized for not helping those with serious problems, such as psychosis, or those from marginalized communities. Some of our colleagues work productively with individuals with psychosis, however, while others are working to develop community psychoanalysis or challenge the historical neglect of sociocultural issues while addressing the importance of using psychodynamic approaches with racial and ethnic minorities. By contrast, the apps avoid such complexities, market themselves optimistically as “the #1 app … that works for everyone,” even while selling simplified self-help tools.

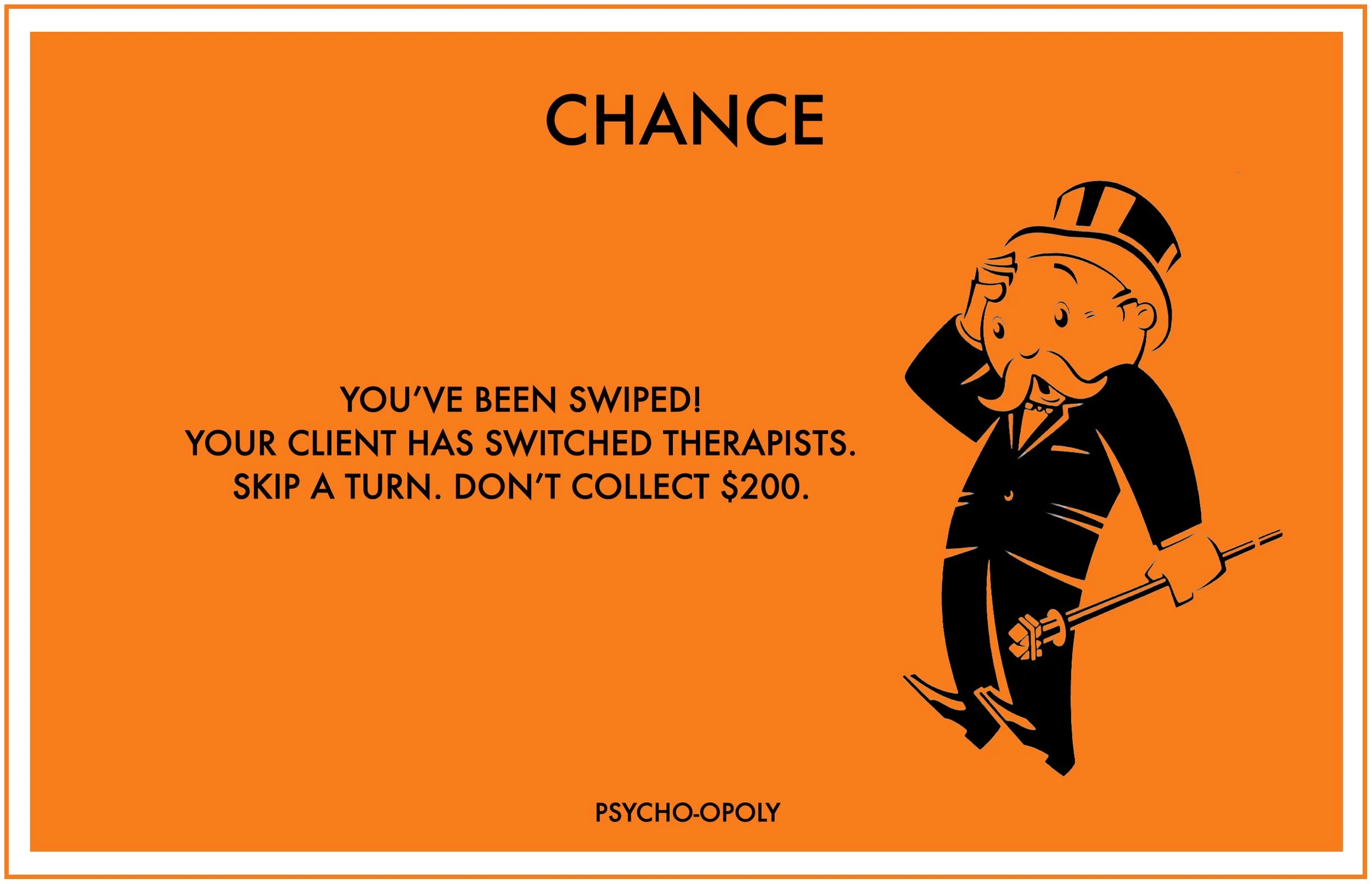

Importantly, many apps are selling what the technology affords and what the market allows—not necessarily what’s effective mental health care. For example, therapist-matching apps, such as BetterHelp and Talkspace, are selling features that let customers text their therapist at any time of day or night, 24/7, and switch therapists with just a swipe on the screen. These features are not evidence-based or necessarily useful; dropping a relationship with one’s therapist without discussion or exploration can even be counter-therapeutic. Further, these features aren’t even ones that the public desires. In a new market research study conducted by my colleague Santiago Delboy and I on behalf of Psychotherapy Action Network (“The Therapy World Has Changed: Where are we now?” which updates and expands our 2021 study), the public clearly stated that they were not interested in these features. What they cared most about was privacy, perhaps knowing that many tech companies routinely sell private customer data for their own benefit, such as to improve their advertising targeting on social media sites. (See the FTC action and fines against BetterHelp.)

With their concerns about privacy, the public also is aligned with Yuval Harari, who claims we now live in a “post-privacy world,” in his latest book on AI and information technology, Nexus. He cites the surveillance of CCTV systems that follow us as we move around cities, as well as the formerly private information we now willingly give away to companies for free—from hotel reviews to Google searches on anxiety. In these ways, we are helping the tech companies and their AI algorithms gain more information, more leverage, more control over our choices, thoughts, feelings, and minds.

Beyond new products for consumers, private equity is also executing its playbook with therapists and group practices by amassing them into ever-larger groups that span the nation. I recently interviewed a therapist whose small regional group practice was purchased by company that’s publicly traded on the NASDAQ fueled by venture capital funds, with over 500 clinics around the country, staffed by over 7,000 clinicians, accepting 160 insurance plans. Their sales pitch to the small group practice owner? At first, they said, “Things are tough with this pandemic, your small business might be adversely affected, and we have more resources and capacity to ensure stability and security for your therapists.” When that didn’t close the deal, their pitch became, “You should sell to us now, because if not, we’ll just lure your therapists away by paying them more than you can.”

The owner sold, and within a year, the group practice is barely recognizable. There was a mass exodus of therapists, especially after the 1.5-year term of the original agreement. Therapists’ salaries were maintained for 1.5 years, and after that, the new company started renegotiating, lowering salaries while increasing caseloads. The local support staff was let go, and support services, such as intake and billing, were moved to a call center on the other side of the country. The senior leadership quit. Their postdoc training program disintegrated, and they found themselves unable to keep postdocs or hire new psychologists because the pay was too low and the caseloads too high. Instead of feeling like an extended family where therapists felt proud to work, the therapists wait in fear of the next memo outlining a pay cut, benefit reduction, or demand for higher productivity. The spirit, the culture, and the values of the original small group practice have been crushed.

For-profit ventures are also insinuating their way into our educational pipeline and threatening the formation of new clinicians entering our field. In a strange example that hits close to home, my graduate school was obliterated by a for-profit company and a private equity fund, with a little help from an evangelical church. The Illinois School of Professional Psychology (ISPP) opened in 1976 and was one of the first schools to focus on deep clinical training following the practitioner-scholar model. It was well-known and highly respected, having trained a number of clinicians in the Chicago area, and had a strong psychoanalytic department. All of this drew me to ISPP, which I chose when I changed careers, matriculating in 2005.

Several years into my grad school experience, ISPP was rebranded as Argosy University, a move that many students and faculty protested. Argosy was owned by Educational Management Corporation (EDMC), a for-profit company, which also owned law schools, art schools, colleges, and more throughout the US. Massive marketing expenditures and false promises of employment lured students to its schools, and soon allegations of fraud, a 99.9% drop in the value of its stock, junk bond status, and a nearly $1 billion settlement to resolve a whistleblower case became part of my school’s history.

In 2017, EDMC sold Argosy to the Dream Center, an evangelical Pentecostal organization, which funded the purchase in partnership with a private equity group. The Dream Center had no experience in higher education. In March 2019, all Argosy schools closed abruptly, mid-semester, with virtually no notice. Students, some mere months from graduating, faced the prospect of taking on more debt to repeat classes at a new university, and faculty were left hanging, unemployed and unpaid. Everyone was shocked, although had we followed the money, we wouldn’t have been. Students with federal loans had not received their stipends for months prior, as the Dream Center funneled the government money to their own operating budget. (ISPP did manage to reconstitute itself and now operates as a small program within a local university.)

Corporate Values vs. Psychoanalytic Values

If the annihilation of successful group practices or educational institutions isn’t harmful enough, it’s the values that undergird the private equity business model that are most alarming and potentially destructive. Here’s my gloss on these new values that we’ll see entering our field more and more, through new products, services, apps, ownership structures, business models, therapist incentive structures, and more. These values are taking corporate America and capitalism to extremes.

Disrupt! Move fast and break things! Investing and building for the long-term are not important. Most of corporate America generally cares about building assets and relationships with customers for the long-term. For example, Coca-Cola advertises to kids and teens and wants them to remain with Coke products throughout their lives. Ford Motor, prizing customer loyalty, wants each of your new vehicles to be a Ford. In contrast, private equity cares mainly about extracting money from the businesses it owns today.

Bigger is better. The goal is maximum growth, often measured by number of downloads or users. These numbers are then characterized as “improving access to therapy,” when in fact there is little connection between the two.

Just make it look good. Marketing is key: high production values, glossy ads, top-notch app design. It’s much more important to make things look good than to provide evidence-based care, have well-trained and qualified therapists, ensure therapists’ working conditions, or protect ethical boundaries.

Optimize user experience. Make it convenient, easy to download and use, gamify your mental health by rewarding users for completing modules or checklists. Gear the user experience towards maximizing “customer satisfaction,” which therapists know has no correlation with quality of care or therapy outcome.

Your data is ours… to collect and mine, to improve our advertising targeting, product development, and customer retention. Privacy and confidentiality are not of interest; venture capitalists aren’t licensed nor bound by any code of ethics. Algorithms will match you with therapists based on variables that may be irrelevant, but they can be captured. As so many of us have learned with our free social media and Gmail accounts, we are the product—and a commodity at that.

Allegiance is for losers. Investing in the long term, whether it’s a geographical region or product category, or developing partnerships with other companies or suppliers, or building long-term relationships with customers (the stuff of branding and emotional associations) are viewed as inefficient and costly things to be avoided. Efficiency is king, and ruthlessness is often the means. Going for maximum financial gain is the most important thing, more important than human needs, moral codes of conduct, trampling on the needy and the vulnerable.

The market knows best and is more important than fairness, equitable income distribution, the environment, individual health, self-determination and wellbeing—let alone healing.

These values are not just antitherapeutic, but they are contrary to much of what we stand for, what we’ve learned in training, what informs the settings and conditions necessary for doing our work, and how we try to help our patients heal and grow. They certainly reside in a universe far removed from a psychoanalytic one, and the fundamental difference separating these universes is that we truly and deeply value people. We center the relationship between the patient and clinician. We aim to understand and care for our patients in all of their emotional complexity and ambiguity. We respect and honor differences, explore beneath the surface layer of symptoms and defenses, know that therapy is not always an easy experience and value the courage of our patients in facing themselves, their histories, and their issues. The hope of healing sustains us and guides the treatment, and we aim for things you just can’t put a price tag on—freedom from suffering and personal growth and transformation.

As a field, we must stand up for these values and fight against the values of private equity. This doesn’t mean we should push away technology or paint tools such as AI with a broad black brush. I hope that smart, innovative individuals who also are guided by care, empathy and respect for others, and a thorough understanding of the evidence base will figure out ways to use technology so that it helps therapists work more effectively and reduce suffering more quickly. It would also be useful to leverage technology to reduce or remove the administrative burdens imposed by insurance companies and middlemen, such as the increasingly popular practice management companies that place themselves in between the therapist and patient, or take the bolder step of replacing insurance companies altogether with AI systems, as proposed by Todd Essig. Those are gains and efficiencies that would be worth investing in. We need to raise awareness of the losses and hidden costs associated with the financiers’ new values, business models, and products, and refuse the financialization of our inner lives and human relationships. We must also educate the public, policymakers, and other mental health professionals about the value, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of psychoanalytic treatment.

Remaining True to Ourselves

The problem of encroaching corporate business models and values is not limited to crises such as the pandemic. It is a general problem for clinicians and the public moving forward, especially when we confront the private equity playbook and values which put capitalism on steroids. I see psychoanalytic values as not just infusing our work and our theories, but also our advocacy, our communications, our connections with the public. We should speak to them with the same respect and regard we feel with our patients, honor their ambivalences about therapy and their all-too-human desires for a quick fix, acknowledge the shortcomings or overreaching of our field, speak plainly about the benefits of our work and navigate, with curiosity and humility, this increasingly technological world which impacts us all.

From PsiAN’s research studies, a majority of people stated they want to get to the root of themselves and their issues. They also view therapy as an inherently valuable undertaking—one that’s worthwhile and which they themselves are worthy of. They value the relational aspects of therapy and doubt that healing will come from an app. Thus, the public’s preferences and the evidence base align. If we remain true to our values and invest where it really counts, we should be able to solve problems of access, sustain our profession, and show the public that healing is possible and available to them.

Linda Michaels, PsyD, MBA, is a psychologist in Chicago. She is chair and cofounder of the Psychotherapy Action Network (PsiAN), consulting Editor of Psychoanalytic Inquiry, clinical associate faculty at the Chicago Center for Psychoanalysis, and fellow of the Lauder Institute Global MBA program.

Issue 59.1, Spring 2025