Having a Word

Bewitchment and confusion in analytic dialogue

By Darren Haberstillness in blue by Prachie Narain Jackson

“So,” he said at the top of the analytic hour, “where should we start?” He looked at me expectantly, with a bit of a chuckle. Anxiety, perhaps, or bemusement?

He’s holding out, I thought, determined to upend this tediously persistent chess match, which had us stalemated.

This was a recurring theme with Jeremy, a pleasant but rigidly organized patient in his mid-30s, who sought my help in finding a partner. He was stuck at the starting line, as were we.

Jeremy had trouble starting new ventures; he wanted a new job but feared it (or he) would not measure up. Same with finding a boyfriend. Identifying as bisexual, he had decided to pursue men, though anything beyond a fling was difficult. What if he were rejected by someone he really liked, or ended up stuck with someone he hated?

Jeremy grew up an only child in a Midwestern suburb that was tolerant yet still heteronormative. He found sexuality confusing and shameful, as with so many of his developmental desires, including in his social life with his straight-edge friends who were viewed skeptically by his helicoptering mother. His mother endlessly overstepped, with Dad uninterested in anything besides his work. Jeremy related this to me with a bemused detachment, with flashes of a simmering cauldron he dared not express.

His parents constantly, bitterly fought, divorcing when Jeremy hit puberty (“ten years too late,” he quipped). His workaholic dad left the house and his son’s life, Jeremy now coerced into a surrogate partner/caregiver role for a mother often bedridden due to a variety of illnesses, including a growing dependence on painkillers. When her prescriptions ran out early, she became rageful. He told me how hard this was … for her.

Jeremy’s mother kept him on a tight leash well into his teen years. Yet I too soon chafed against the constraints of Jeremy’s silences, as if he were awaiting me to fill the gaps, as if I could peer into his own mind. He often apologized for being “a difficult patient.”

I observed flashes of Jeremy’s wounded anger towards his mother’s rage and father’s absence, followed by a crippling guilt, at which point the conversation ended.

The atmosphere was suffocating at times. Affectivity of almost any kind was intolerable for him, intensity fast neutered by jokes or diversions. He once asked if he won the award for most difficult patient. “I imagine what you’ve lived through is difficult,” I said. “That’s the self-centered view,” he responded, as if it would be immoral to recognize his own suffering.

Affectivity became akin to original sin, fruit from the poisonous tree. Was I the snake in his Garden of Dissociative Eden? Either way I couldn’t win; he heard my curiosity as criticism.

Forget being on the same page; we weren’t even in the same book.

Accommodation and Dissociation

Jeremy, like many patients, initially arrived at therapy with the hope of being more accommodative at work, less irritated with inept superiors and his mother especially, banishing the anger that fast-tracked him into guilt. He still walked on eggshells with her.

He also admitted he was well defended with me: “I’m a black belt, you’ve met your match,” he said, again with a chuckle that annoyed me, as if he took pride in the self-defense that kept him imprisoned (it was safe there).

“Do I want to change?” he would ask at times, followed by long pauses. It almost seemed at such moments that it was up to me to persuade him of the benefits of change (of my efficacy?), with him on the sidelines, arms crossed with skepticism. My attempts to understand this dynamic were ineffective, given his reactive self-blame, which alternated with a subtle, intellectualized superiority.

Often at the start of sessions, he would ask what threads to pull on that day; he was accustomed to accommodating, and now I was to accommodate the pattern. Curiosity about my part in this, after nearly a year of treatment, again sent us in circles. “I don’t know why I don’t know what to talk about,” he’d say, grinning nervously. “I was hoping you could tell me, though I suppose that’s ‘against the rules.’ I guess nothing feels all that … urgent?”

Then, silence.

Yet when I tried introducing a previous theme, he became impatient: “This feels like a dead end.” While my goal was to open emotional windows for ventilation, his was to keep them locked while complaining less.

Jeremy was extremely bright and often humorously engaging, while also organizing nearly all life activity (including therapy) into “checklists.” “Just gimme the boxes to check and I’m a happy camper,” he would say.

He managed a local chain of juice shops and “ran a tight ship.” He was kind to employees but very hard working. Even a drop of frustration towards a fumbling employee or clueless supervisor, sounding mild to me, resulted in surges of guilt.

I observed that his agentic moves were framed mechanically, ever calculated; he agreed with that observation but couldn’t imagine an alternative. When he said he hoped to “nail down the dating issues,” this too was ticking a box, while recognizing this was “probably the wrong approach.”

He was loath to discuss his binge drinking and overeating, but he did reluctantly acknowledge these occasionally. To me it made sense, given that so much of his emotionality was on lockdown; these binges were like prison escapes. Yet this topic too was foreclosed, as these shameful binges (the spirit escaping from its cell) should have ended long ago. “What’s the fix?” he asked, with an ironic smile, like a riddle whose answer confounded me.

Bewitchment by Language

I noticed we repeated the same phrases and rituals week to week, at the start especially. How was the week, Jeremy? Did they replace that inept delivery guy yet? I found myself hoping the right remark or comment from me might shake things loose. “Your boss sounds a bit Mom-ish,” I would say. “It all comes back to Mom, eh?” he would say, with a small laugh. I explained why I made that connection, arguing for more visceral statements given the futility of intellectualizing—although this was just more intellectual explanation.

We both somehow believed that the “correct words” would set us free, a symptom of what philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein called the “bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

Wittgenstein understood that words are powerful. It is easy to forget that our familiar, day-to-day speech does not directly represent our reality or experience (like photorealism) but rather paints a perspective on how we feel about and view that experience. We take for granted how we think and talk with others, as the distinctiveness of our viewpoint—the frame through which we view the world—goes unnoticed.

What we reveal in speech is not how “reality” is, but how we are. Many dissociated patients see things concretely, as if their words directly portray how the world is: language-is rather than language-as (concretization versus metaphor). Such use of words bypasses any notion of framing, of personalized speech, or (most pertinently) the value of such personalization, of speaking a world of one’s own.

Therapy helps make the frame visible by developing a common language between participants for reflecting on the language of everyday experience and how the patient has come to see things in a certain way, the unseen perspective that in Jeremy’s case tightened his life’s possibilities like a noose.

This is a nuanced idea, difficult for those desubjectivized in traumatizing early surrounds. By this I mean the destruction of a personal viewpoint, of the ability to speak spontaneously, from and not of one’s centered presence.

When Jeremy spoke of his “failures” at dating (without much sustained effort), he described his being a failure, a direct equivalence, bypassing the poetry of existence, deadening his experience, the hangman’s verdict ever hovering nearby (like his mother’s skepticism and father’s nonpresence). The strangling viewpoint remained unseen: a dimly befogged yet permanent lens through which he viewed his existence; caught in this frame, this ironic, precocious child (now man) never stood a chance.

When underlying affectivity is deflected or avoided (and Jeremy and I both contributed), reflective space collapses. Participants end up awaiting the Godot of some magical statement or insight, as if words alone are transformative, rather than an expanded dynamic allowing the patient to take the risk of a more freely expressed emotionality.

The main vehicle for change, in my perspective, is the relationship itself and how it manifests in the consulting room. I sensed I was an (unacknowledged) authority figure both tempting and risky for Jeremy, liberating and intrusive (like Mom) or indifferent (like Dad).

How did we end up at such a dead end?

We both somehow believed that the “correct words” would set us free, a symptom of what philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein called the “bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

Mutual Anxiety

We tend to underestimate the power of the unspoken affect organizing our viewpoint; we are driven by unseen feelings, fears, and hunger that appear irrational, threatening to the conscious status quo, both perseverant and shameful. Our dreams reveal to us our demands and terrors, as do our sudden rages, longings, reveries, bursts of laughter, or quietly unsettling angst; a key analytic idea starting with Freud.

Anxieties especially befog our perspective and provoke binaries, either/or scenarios leading to obscuring speech, rather than a transparency of feeling; words too become thing-like, pawns on the board, as we search for certainty, something to grab onto.

A transactional relatedness emerges, drained of pulse and blood.

As for Jeremy, his anxiety led to a pensive silence I had trouble tolerating, occasionally falling into the trap of explanation. Our dialogue could show but not directly explain or illuminate psychic dynamics—not revealed like something hidden behind the couch (or “in” the unconscious).

Jeremy remained in the dark bewitchment of rational safety, using the right idea or phrase to detour pain. But such arid safety carries its own risks, such as searing isolation and self-doubt: an imprisoned subjectivity devalued by his mother’s criticisms and demands. This became the unseen backdrop of his world, painful and brutish. Rational speech enforces rationality, an endless chain of words: labyrinths leading nowhere. I missed a chance to grab the golden thread when I heard Jeremy’s complaints about “dead-end topics,” as he was protesting longstanding neglect on my part (transferentially, though I missed it at first).

Such was the game that had us stalemated. Language game, incidentally, is Wittgenstein’s metaphor for the contextualized meaning of our words and ways of speaking, embedded in specific eras, idioms, identities, genres, and so on. Hip-hop lyrics, internet memes, political slogans, Marvel comics, inside jokes, chess moves, or analytic theory: all different games. Wittgenstein called language games our “forms of life.”

Analytic life too is lived, not explained or “figured out”. The “figuring out” follows the enactment of affect, when we ask, “what just happened?” Language is always catching up.

Our therapeutic concepts are entry points and guideposts serving our verbalized investigations; they suggest a means of understanding. Another way of putting this, which Wittgenstein well understood (along with fellow Austrian Freud, a contemporary whom Wittgenstein admired—with caveats), is that language, at its therapeutic best, foregrounds a personalized backdrop of represented life experience requiring interpretation, not a direct portrait of life as it is (and we are).

Life itself—the juice of life, the yin/yang of desire and anguish—becomes the colorizing source of our words, without which the latter are thing-like rather than personalized. This process is shown (enacted, lived) rather than said.

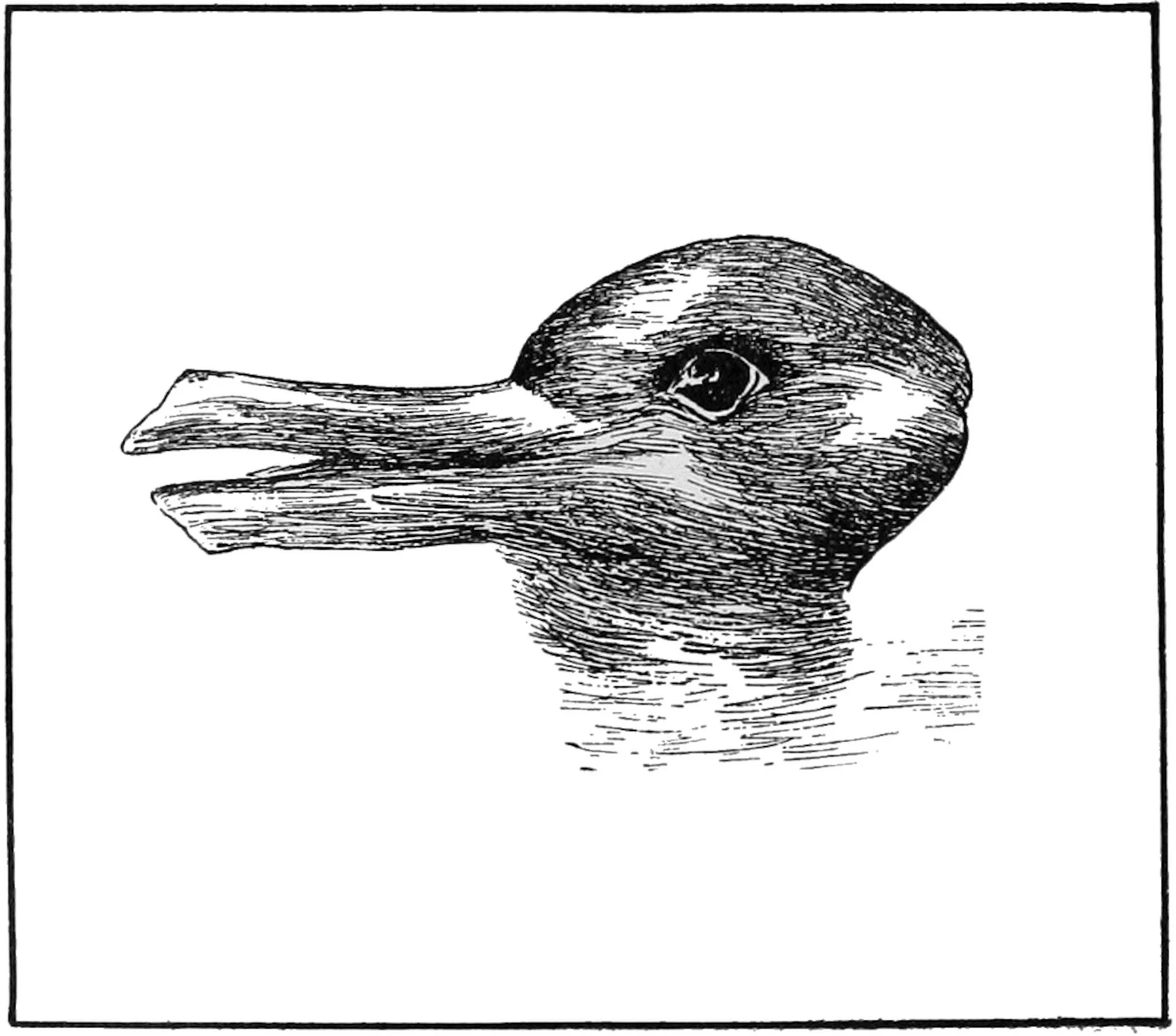

What I overlooked was Jeremy’s difficulty in expressing basic emotion in the face of an other both benevolent and threatening (i.e., his therapist). We were still learning to survey our shared terrain, where only a rabbit or duck was visible (never both), to cite an old visual illusion discussed by Wittgenstein (sometimes referred to as “Jastrow’s rabbit”). Our seeing one and then the other is also unexplainable; we can’t say for sure what “shifts” our viewpoint, like suddenly “getting” a challenging poem or film: Ah, now I see it!

Meanwhile we both remained outside Jeremy’s affectivity looking in: Indeed, he knew no other position.

Jastrow’s rabbit, which first appeared in a German humor magazine in 1892, was named for Polish American psychologist Joseph Jastrow and then made famous by Ludwig Wittgenstein as an illustration of the concept of “seeing-as.”

I tried too hard to fill the void of unspoken suffering: like explaining how medicine helps what ails you, instead of listening to the pain, to understand what kind of relief was sought.

My own blind spots arise from trying too hard to “figure it out” for the patient, as if this were possible, as if words alone might “unspell” rigidity or befogging anxiety. (Who are these explanations for?) In fact what was needed was to be a bit dumber, lean into ignorance, embody curiosity without hope of an answer. Cleverness alone is not enough.

“Believe Me”: A New Game

One day I said to Jeremy, during a tense exchange about his struggle to get started, “It’s like you’re deep in a fortress when we begin, I can’t reach you, and I don’t know why.”

“And when you ask why and I say I don’t know,” he responded, subtly exasperated, “it’s like you don’t believe me.” There was actual distress here. He said, “It’s like I … lack the vocabulary.”

I sat up in my chair. Of course he did, because he didn’t know the language game!

I hadn’t recognized it either, because the game was mutually defined. He heard me explaining the “rules,” at times, like explaining what Paris is like instead of actually going there (keeping him, again, outside looking in). In fact his “I don’t know” made me anxious, as if he were wary of me, keeping me on the outside rather than revealing his own alienation. It was this alienation leading to ask him the rules of a new game he could not yet trust, let alone play, as the old ones had constricted him so tightly.

What we needed here was less chess and more Go Fish.

Jeremy had never been allowed to play as a kid—to be a kid among kids, even before his parents’ divorce. (I imagine he came out of the womb reading a book.) Emotional spontaneity was discouraged or ignored; precocity kept the peace, in his avoiding saying “ouch.” He didn’t even know the purpose of its utterance, although “ouch” was at the root of the very language game I was trying to initiate—for him a foreign tongue altogether.

Some patients think that the point of recognizing emotion is to merely name it, like affixing a label, as if said label itself magically contains or transforms. This is why concretizing patients (such as this one) often say, “So I realize I’m anxious, now what?” The bewitched intellect stands its ground.

Wittgenstein has a wonderful phrase for unnamed private sensations, which are “not a Something, but not a Nothing either.” What makes them something is responsiveness and recognition. The child learns to say “ouch” in expecting a response, not to “report” but to relate a sensation of pain or physical distress in need of soothing. These primally tender words carry currency in recognition, a parent learning to discern their baby’s cries. Such cries or other expressions are devalued when a caregiver’s needs take precedence, as when an infant’s distress provokes the caregiver’s anxiety. The ground of relatedness falters; the infant learns its cries are “problematic” for others. (How many times did Jeremy say he was a difficult patient?)

It isn’t a matter of knowing or reciting feeling words but of understanding their purpose in an atmosphere of recognition: the moves or games of spoken coexistence.

I contributed to our stalemate by “explaining” how this all worked, and why affect was important: catnip for the intellect, inviting more fraught and empty chatter. But we cannot explain the value of recognition; we do our best to embody it, while hitting enough dead-ends to bruise our foreheads, albeit committed to banging on (as the Brits say), with as much empathic frankness as possible.

Why did it take me so long to get this?

Jeremy had never been allowed to play as a kid—to be a kid among kids, even before his parents’ divorce. (I imagine he came out of the womb reading a book.)

Throwing Away the Book: A Shameful Memory

Jeremy was so self-critical that I feared my frustration would cause even more shame, as with Mother, a caution related to my own early experience, including an imperative to speak with undue caution to deeply insecure caregivers.

Jeremy had been traumatized by a mother which reminded me in many ways of my own childhood; I too had a parent who shut me down when threatened.

When I was in middle school, I borrowed a book from the library on alcoholic families, amazed that such a book even existed. I left it in the living room one evening, and my father (who qualified as said family) spotted it the next morning on the coffee table. He whitened with rage, furiously whispering for me to get that goddamn book outta here. I duly, shamefully obeyed.

Words now became even more powerful to me, darkly bewitching in their capacity to harm others and to push them away; the book became a tome plucked from Voldemort’s library.

This is why I misheard Jeremy’s “I don’t know” as coyly deflecting, akin to “I don’t care” or “get that question [book] outta here.” In fact Jeremy was protecting me from his “burdensome” need for safety and understanding. What I missed was the despair behind his words, shamed by the sin of not knowing, silently shared.

Jeremy too had been taught that honest self-expression is threatening and thus verboten. We remained in the grip of a fear of over-exposure, of any exposure, hiding behind concepts.

Still we kept at it, and in doing so I showed Jeremy he was not “too difficult” for me, disconfirming his worst fear (abandonment), even if he lacked the vocabulary—the relational “permission” and experience—to play a more intimate game.

I told Jeremy that this “vocabulary,” in his illuminating statement, was simpler than we were presuming. Perhaps all we needed was a way for me to help him say, or understand what was scary about saying, “His absence hurt and pissed me off” or “Why was Mom such a bitch sometimes?” and “but I feel like shit in saying that.”

Eventually he was able to express hurt and fury at his mother, and father, with the remorse that followed—as if he were killing her, a conclusion common to parentified children.

Often the languaging of the problem reveals the problem. An addicted patient describes the frustration of not being able to figure out how to stop or control drinking, a frustration leading again to the bottle. A new language game is needed entirely, one speaking to psychic or (if you like) soulful suffering.

Consider the term “dissociation.” “Dissociated affect” indicates something pushed aside or disavowed, like a child exiled into hiding. But that something eludes definition, giving it a hazy quality.

I got stuck ruminating on what was being dissociated, as if naming it alone were restorative. But what matters is not just what is dissociated, but what purpose is served by the evasion. We can get caught up in the what and become dissociated ourselves! The pushing away is as important as the “what” disavowed: an unspoken no-thing until it enters the something-ness of analytic dialogue.

Here we are called to dwell in what Wilfred Bion, following John Keats, called “negative capability,” the uneasy acceptance of not knowing, despite our being seen as experts, while committed to listening and observing as closely as possible, trusting that the pieces will come together via our analytic presence and associations. Our expertise is paradoxical that way, as much of our expertise consists of making space for what is not “there” yet.

At times, when we analysts are in touch with a well-defended patient’s unnamed affective stirrings, we feel pushed away, abandoned, exiled from our “home base” of theory, due to apparent inadequacy; our job after all is to know, which can be misunderstood as akin to knowing a recipe or the notes of a song. Yet analytic music is mutually composed.

In fact it is the very negation of rawly spoken emotional truth that the patient has lived with, and compulsively repeated (enacted), for a lifetime. This void-like presence, the presence of “charged” absence, calls out for creative use of words.

Silence is often safety under an authoritarian regime, whether that regime is political or psychical. It takes time to see how this works for this patient, to fill the chasm of silence with curiosity and desire for authentic speech in the face of such stubborn inarticulation. And so the work remains difficult. To paraphrase Bion, patient and analyst develop a means of communication while communicating, like drawing a map as you follow it.

But one cannot explore the terrain via a map alone, as if trying to describe a city via a ground plan. Relationships are like cities visited, explored, not mapped from above (the language game initiated by traumatizing environments).

The analyst, too, must set aside their theoretical “map,” banished from the lush gardens of familiarity into a patient’s unspeakability, a terrain more aridly foreboding than our case studies often indicate, as seedlings of spoken language games find root in the something of deeply heard expression, those shouts in the wind finally arriving home.

Darren Haber, PsyD, MFT, is a psychoanalyst practicing in west Los Angeles. His book, Circles Without a Center: Addiction, Accommodation and Vulnerability in Psychoanalysis is was published by Routledge. He publishes a weekly Substack column called “Hearing the Worlds of Others.” He has published online at various outlets, and appeared numerous times in the journals Psychoanalysis, Self and Context, and Psychoanalytic Inquiry.

Potentially personally identifying information presented that relates directly or indirectly to an individual, or individuals, has been changed to disguise and safeguard the confidentiality, privacy, and data protection rights of those concerned.

Published October 2025