“Three Essays” and the Blue Dot

Lessons from a life in analytic training

By Cara ManiaciIllustration by Austin Hughes

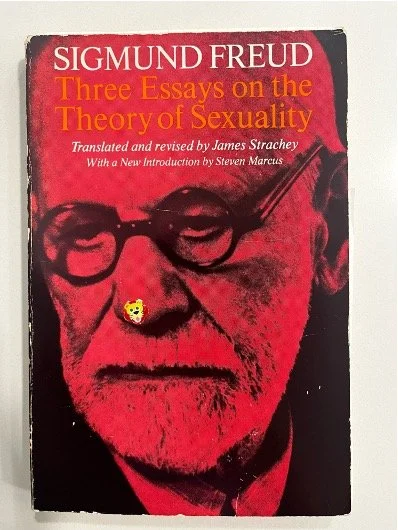

At age 24, in a daydream-like reverie during a graduate class on gender studies, I drew a tangled, scribbly little dot on a book cover. The cover featured a photograph of the author. But this was not just any book cover, and not just any author. The book was Freud’s Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1999, Basic Books edition). And the blue dot was quite indelicately placed at the tip of his nose.

The photograph is a close-up in black and white with a monochrome wash of red over the image, like a vintage Blue Note album cover. Perhaps the red was meant to suggest Freud’s concept of Eros. Perhaps the retro look had something to do with declining popular interest in psychoanalysis—rendering Freud in a bygone era. Freud’s downcast expression in the photo seems to suggest some engagement with his own mind, not the reader’s. Certainly not mine. What does Freud care about me? I might have thought at 24 years old.

And yet I have cherished this book. I love these essays for recognizing and celebrating the range of sexual experiences. I struggle with these essays for also narrowing them down to the primacy of reproductive heterosexual intercourse. They are both a turn-on and disgusting at various points. And it was in these essays that I fell in love with psychoanalysis.

Like a staid companion, this book has followed me from its original purpose of graduate studies in art history through four incomplete psychoanalytic trainings between 2006 and the present. Throughout our relationship that blue dot has vexed me. I had literally and figuratively de-faced the patriarch of psychoanalysis. Perhaps it was an Oedipal gesture. Perhaps it was a nod to Freud’s friend Fliess, who believed cycles of nasal congestion were related to overall physical and psychological health. It was an irreverent action, inflicted on an object that over time I came to treasure.

Even while the blue dot haunted me, I could not part with this transitional object. Over the years, my sense of pride in having this gorgeous, crimson-tinted edition of the Three Essays—not the Norton edition with its more reserved navy blue—was marred by the infantile doodle. I considered purchasing another copy with the same cover design, but years’ worth of marginal annotations and underlines were etched on the pages. This dot troubled me so much that at one point, I took one of my daughter’s fingernail stickers—a tiny kawaii lion—and covered the blue dot to suggest that she had been the vandal.

The unconscious drive to mark this book 25 years ago has taken almost another quarter century to reveal its message. Psychoanalysis teaches us that unconscious motivations reveal themselves over time, in mysterious ways. Unraveled, the doodle reveals personal conflicts around education, class, and family that were entangled in my experience of becoming a psychoanalyst—that is, if I can call myself one now.

Eighteen years in, after many stops and starts, I’m still not finished with psychoanalytic training. Amidst learning about the mysteries of the unconscious and the drives, I have learned through the ordeal of my own psychoanalytic education that training institutes are economically exclusionary, socially insular, and hampered in many ways by their own bureaucratic organization. And yet my psychoanalytic education has also been a powerfully transformative experience that has brought meaning and creative potential into my life.

The blue dot tells some of that story. Other books tell more of it.

Photo courtesy the author

Anastasia and Nicky

The Three Essays is among many books formative to my development as a psychoanalyst. Not long ago, I rediscovered what may have been one of the very first. When I was a preteen, the Anastasia Krupnick series of young adult novels by Lois Lowry was a favorite. My own daughter, now 16, has had a few of these on her bookshelf as well. A few months ago, compelled by its title, I opened and reread one of them: Anastasia, Ask Your Analyst.

In this story, 13-year-old Anastasia—like myself at that age—finds her family mortifyingly shameful. Quite distressed about it, she proposes to her parents that she see a therapist. Callously, they laugh it off, explaining that nothing’s wrong with her: All thirteen-year-olds are embarrassed by their families. A week or two later, while thrifting with friends at an estate sale for a deceased psychoanalyst, Anastasia finds a bust of Freud, which she purchases for herself, announcing to her parents she has found herself a psychiatrist after all.

Throughout the book she talks to her Freud statue about the growing pains of differentiating from her unique family. One might say she develops a transference to it—she envisions the statue alternately grinning and grimacing at her confessions. She shares with Freud her intellectualized attempts to understand sexuality (as in her school science fair project studying the mating habits of hamsters) and to grasp the significance of gender, class, and ethnic identity in more informal studies of her parents’ suburban social interactions. The bust of Freud, another transitional object of sorts, offers Anastasia a screen onto which she projects her conflicting, increasingly complex emotions and attachments amidst the frenetic swirl of her own family life and a culturally diverse world.

The book is sprinkled with stereotypes that seemed permissible in 1984 when it was published but feel ridiculously unacceptable today, such as the impossibility of a Chinese family naming their son Stanley Wong. But the stereotyping is most pronounced in the characters of Nicky Coletti—Anastasia’s younger brother’s preschool bully, who to the family’s surprise turns out to be a little girl—and her mother Shirley. Mrs. Coletti is a caricature of a middle-class suburban Italian American woman—unsophisticated, but arrogantly so. Her provincial ignorance is highlighted as she critiques the Krupnick’s old home with its lack of wall-to-wall carpeting, Mrs. Krupnick’s choice to work outside the home, their homemade crafts and wooden toys. In one chapter, Nicky runs amok through the house like a tornado, turning everything upside down in her path.

As the dust settles when the Colettis leave, amidst the spilled perfume and broken toys Anastasia discovers something that astonished me when I reread this book as an adult, and as a psychoanalyst: Nicky had drawn a blue dot on the tip of Freud’s nose.

Anastasia had Freud. And I had Anastasia, who took me to Freud. Both of us were intellectually curious adolescents, experiencing the growing pains of recognizing our families could not offer us everything we wanted for ourselves. We both wished for a more formulaic mom who could offer us space to develop into the kinds of women we aspired to be. But while Anastasia found her artist mother’s down-to-earth style mortifying, I felt embarrassed by my mother’s being more Shirley Coletti than Katherine Krupnick. Anastasia’s father was a Harvard professor, and her mother a successful illustrator. Her parents shared household and childrearing duties in a more egalitarian fashion than my own. My mom was primarily a stay-at-home mother, who in various ways struggled to break out of patriarchal norms that kept her from developing her own professional life. Both of my parents were college-educated, but education for them was not the launchpad into a life of one’s own, professionally or otherwise. Traditional Italian American values kept them close to home in every way, and my arrival early on in their young marriage reinforced their dependency on the larger family system.

With Anastasia’s Freud in mind and a bit of dabbling into The Interpretation of Dreams from the red leather-bound Great Books series my parents purchased to decorate the living room shelves, I went to college in the mid-1990s with a vague idea that I would study psychology and learn more about the unconscious, fantasies, and the like. Instead, I walked into a large lecture hall seating 250 students at 8:20 three mornings a week to learn about neurotransmitters and the hippocampus. It was not until I took a class in the English department that I read Freud, and much later, in graduate school for art history, that I learned about Donald Winnicott in a discussion about transitional objects. Somehow Anastasia and her Freud stayed with me like my own transitional objects, more than I consciously realized over the years, eventually guiding me into my own psychoanalysis that led me into the field via a master’s in social work.

Interminable Analytic Training

I began analytic training in good faith, figuring I could finish in five or six years, perhaps with a break to have children. In my unconscious I held the Krupnicks’ cozy intellectual lifestyle in mind as aspiration, but what I did not realize until recently was how Nicky Coletti stayed with me, too—my irreverent streak, my frustrations with institutions that did not represent the complexity of my life circumstances, let alone that of many potential patients whose lives could also be transformed by psychoanalysis.

I paused training the first time to become a mother. Two years later, I returned to a different program—a brand-new four year program intended to redefine and modernize analytic training. Ironically, I was not able to complete this training because the institute refused to conform to ambiguous and unsettled state licensing requirements, choosing instead to shut down the four-year program in its second year. It took me eight more years, after a divorce, second child, and second husband, to scrape together the time and money to return and finish.

I’m still not done.

I’m still not done with training because of life. And because training is incredibly expensive— the cost for courses and training and analysis adds up to tens of thousands per year. It takes 8–10 hours of potential earning time in a week for required personal analysis, clinical supervision, and coursework.

Elizabeth Corpt speaks of the “assumed yet unspoken class ideal” psychoanalytic training institutes uphold, a residue from the time when in the United States only MDs were permitted to be psychoanalysts. Even as social workers like me were brought into the profession, these ideals remained in place, particularly in New York City where I have worked and lived. These ideals express themselves subtly: clothing, real estate, vacations. (For instance, the time in my second-year social work internship, which was at a small analytic training institute, when the supervisor announced to our group that he just returned from St. Barthes. Incredibly, I was the only one in our cohort of interns who had not also been there.) These ideals also express themselves structurally: weekday classes, the expense of training and personal analysis, time taken from work. But many early-career candidates are also trying to balance family and work, and a two-income household is often imperative, especially in an urban setting. Scholarships at many institutes do help. Yet reforms have moved at a snail’s pace. Ultimately, it seems that training is designed for—and arguably to maintain, as stated by psychoanalyst and social worker Carter J. Carter—an elite class that I was not born into.

In the essay “Damaged Life,” from the book Disorganization and Sex, Jamieson Webster writes that from her chair in the analytic consulting room she has observed that we find a kind of primal, sadomascohistic identification with the systems of power that regulate and constrain us, from capitalism to misogyny. If subjects often form painful identifications with systems of power, then psychoanalysis must also ask whether its own institutional forms—its theories of transference, its training practices, its organizational structures—are repeating those same dynamics. In a recent podcast interview, Webster says this question, which ought to be central, “isn't even asked by the institutes.”

Analyst Emanuel Berman, in his book Impossible Training, avers that “the core of psychoanalytic training is not the teaching of any specific technique or specific theoretical model, but the development of a unique site of mind and of particular sensitivities that facilitate better empathic and introspective perceptiveness.” He asserts that the vigorous study of psychoanalysis within in its historical context “encourages a continual process of creative personal theorizing.” The psychoanalytic institute can be a container, a transitional, transformational space in which individuals develop these sensitivities, but like any good transitional space it must also be transformed by what it is holding.

Unfortunately, this is currently a container that is readily accessible only to a select few: generational wealth, doctors, married into money. Which means that its products—psychoanalysts and theory—are also representative of that select few as well. They are shaped by the container.

When you add up all of the dollars and hours that go into training, of course one wants a finish line, a gate to gatekeep. One tendency is to reactively and defensively proceed with the attitude that “this is just how it’s done.” Such rigidity is contradictory to the spirit of psychoanalysis, which emphasizes reflection on the impact of the past so as not to be confined by it. For me this meant approaching my current training institute and obtaining credit for much of my prior experience in analysis and training. Other institutes should consider more powerful outreach to the many strong, analytically minded clinicians for whom training is impossible due to limited time and finances.

As a profession, we also might need to reconsider the significance of certification. Does one need a credential at all to be a good-enough practitioner of psychoanalysis?

Credentials protect consumers and ensure the integrity of a discipline. How can this remain meaningful and substantial without also reinforcing preexisting power structures? Carter talks about bringing psychoanalytic training back into the state university in order to open it to a wider public. Two years ago, this would have seemed like a viable solution, but with the current assault on higher education by the federal government, it looks much less promising. Unlike Carter, I do not want to abolish the psychoanalytic institute, but perhaps we should rethink its purpose.

Back to Middle School

With so many obstacles to training one has to wonder how people still feel compelled to join this profession in the first place. I have been thinking about this lately, asking colleagues how they found their way to psychoanalysis, of all things. Many found their way to psychology first and then had a supervisor who was psychoanalytically minded. Many started through their own personal therapy. For me, the seed was planted far earlier, blown on the breeze to somewhat inhospitable ground—perhaps in that first encounter with Anastasia’s Freud.

A psychoanalytic education can come in small ways. When my daughter was in eighth grade, I gave a talk for her middle school’s career day in which I outlined the various avenues to becoming a therapist, including the distinctions between the professional degrees LCSW, LPC, PhD, PsyD. I explained how therapists are informed by science and theory that shape their beliefs about what is helpful, and I gave a little introduction to behavioral approaches and psychodynamic ones. I used a case example to illustrate the impact of trauma and the resonance of the unconscious in the emergence of symptoms in later life. In this stuffy, fluorescent-lit classroom there were certainly a few Anastasia Krupnicks for whom some of this was familiar territory, but also quite a few Nicky Colettis for whom this was completely novel. Maybe in a decade, some of them will find their way to studying psychoanalysis as well. Psychoanalysis reminds us of how inside we're all a little bit like Nicky—messy, uncontained, irreverent. And psychoanalysis needs some of that spirit, too, in order to remain vital.

Sidebar: Up and Out of the Neighborhood, and Back Again

In “Damaged Life” Jamieson Webster responds to Jacques Lacan’s notion that we have a “choice of neurosis,” a choice that is unconscious, structural, and made in response to the circumstances of one’s birth. She writes, “From this, one has to invent a solution in order to live.”

One way of inventing a solution is through cultural education—a way up, out, and inward, providing new ways of understanding not only the world but one’s self. Philosopher Agnes Callard refers to this in an essay in which she explores the transformative action of the relationship between the main characters of Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend. This book is the first of Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet which traces the lives of two girls, Elena and Lila, as they come of age amidst the demoralizing silence and poverty of their neighborhood in Naples, Italy. In self-psychological terms, Lila and Elena serve as complex selfobjects for each other, alternately idealizing, mirroring, and twinning. Callard describes the process in which they compete with each other but also motivate each other. Each of them is compelled to avoid the fate of their own mothers and other women in the neighborhood who are tied down by childrearing and intimidated by threats of violence from the local crime family.

While not an official part of my psychoanalytic canon, these books have been formative for me in other ways. I read them voraciously when they were initially published, identifying with these characters who came from the same kind of southern Italian neighborhood that my own relatives left over 100 years prior to emigrate to the United States. And in my own way, I felt an allegiance to these characters who sought to dis-identify from their roots, from their mothers, and from the ruthless social institutions that formed them, even as they were drawn back to them again and again.

Cara Maniaci, MA, LCSW, is anticipating her certification in the Advanced Program in Psychoanalysis at the Westchester Center for the Study of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy in Fall 2026. She has previously written for The American Psychoanalyst, and The Psychoanalytic Quarterly. She is a member of APsA’s President’s Commission on Artificial Intelligence and has a private practice in Pleasantville, NY.

Published January 2026