On Being Jewish

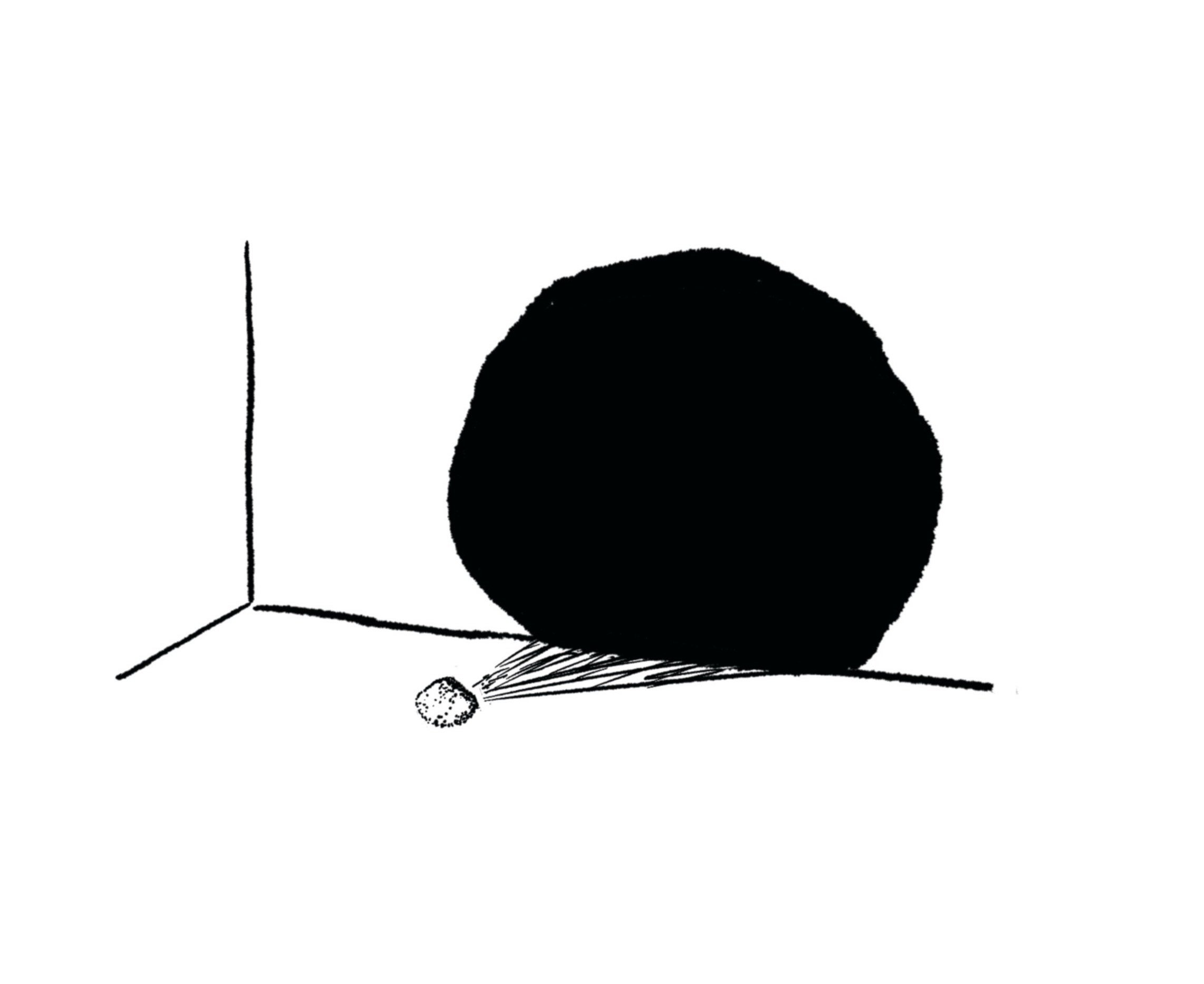

There is something inside of me I can’t get rid of. It weighs me down at the center of my body like a stone.

By Alex DezenIllustration by Cassie Gaffaney

I am an American Jew, born in New York City and reared in the saintly suburbs of New Jersey. A diminished version of our family moved to Manhattan when I was about eight. Practically speaking, we were fatherless and faithless, but we had been that way for as long as I could remember.

In the 80s, being Jewish was a welcomed punchline, most often landed by Jews themselves. Chunk from The Goonies comes to mind—the pudgy little boy who made conspicuous reference to his Jewishness. Not to mention the comedic genius of Mel Brooks’s Spaceballs, which churned Star Wars lore and Jewish neuroses into alchemical gold. This was still, more or less, the golden age of Jewish comedians, a continuation of the indelible Borscht Belt comedy scene: Billy Crystal, Joan Rivers, Rodney Dangerfield.

Being Jewish was so normal, it was nearly forgotten.

My Jewishness is a conflict. My mother was born a Catholic, claimed conversion, then later denied it. My father was born a Jew, remained a Jew in name only, then died of dyspepsia. To many Jews, I am not a Jew at all. To the State of Israel, I’m plenty Jew to apply for citizenship. To the denominations that trend conservative beyond Reform, I will never be a Jew. I have spent a significant amount of time worrying whether I’m Jewish enough, but I’ve spent an equal amount of time answering questions, as a Jew, about the West Bank, Netanyahu, and of course Gaza, as if my Jewishness, while perpetually in doubt, would always be enough by which to hang me.

I think about being Jewish a lot, more than most other Jews I know. I think about the disintegration of Jewishness, of which I am a part. I think about that most notably when people make anti-Semitic comments around me, not realizing (or fully realizing) that I am (or am not) Jewish. Sometimes I’m offended. Sometimes I feign laughter. I am a Jew. I am not a Jew. Ehyeh asher Ehyeh. I am what I am.

I’ve explored this inner conflict on the couches and chairs of several different psychologist’s offices throughout my life, gnawing my cuticles while my anxiety gnawed away at me. Of course, modern psychotherapy springs from similar Jewish neuroses—specifically the neuroses of Sigmund Freud’s Viennese patients, a great number of whom would not survive the Second World War. But many who did survive transmuted Freud’s genius through the postwar diaspora, making New York City—my home—a hotbed of psychoanalytic thought and practice, while others made Palestine a home to the Jewish State.

I am an American Jew. At this point, it’s more of a choice than a conscription.

When the brutal attacks of October 7 happened, I was scared, but not of a further incursion by Hamas into Israel or the wider war into which Netanyahu’s cabal of the extreme and the inept would inevitably—and enthusiastically—be drawn. I was scared about being seen. Being unforgotten. Early Jewish opponents of Zionism, namely the Jewish European socialist labor movement Bund, argued that the most dangerous thing for Jews would be an ethnoreligious state, that, paradoxically, a Jewish state would stoke the flame of global anti-Semitism, which at the time had been kept at a comfortable simmer. “Comfortable simmer” being a consistent program of Jewish annihilation, tacitly—and often overtly—backed by world governments. My family fled one of these pogroms in Ukraine during the latter part of the 19th century, escaping the Pale of Settlement for the shores of New York with nothing but what they could carry. In America, my father’s family found a path to survival by way of alacritous integration and assimilation. They were Jews always. But now they were American Jews, and for the purposes of brevity and peace, just simply Americans.

When I think about Israel, I think about New York. New York is my Israel, as it is to the second largest concentration of Jews in the world. I think about the Haredi boys, the Lubavitcher knuckleheads who try to wrap tefillin around your arm as you exit the Bedford stop on the L-train in Brooklyn. I think about my schoolmates, my friends who argued over bagels and baseball teams. I think about the community, both acknowledged and hidden, in our conversations and in the culture at large. “You know,” my father would often whisper, pointing out some minor character on the screen at the movie theater, “he’s Jewish.”

On October 7, I was scared. When the tanks rolled into Gaza, I cried. I cried because I knew, right in that moment, as did every other Jew in the world, that everything that has happened since would happen. Children would be murdered, families incinerated, communities destroyed, all while world governments bent themselves into more and more complex contortions and contradictions to excuse—and fund—the inexcusable. Some of my friends would become extremists, refusing to either acknowledge the vicious brutality of the October 7 attacks or the horrors playing out daily in Gaza, as if both of those realities could not possibly exist in the same universe, trading the nuance of our tortuous existence for the tiny death of Twitter’s 280-character limit.

I am an American Jew. At this point, it’s more of a choice than a conscription. I’m lucky that way. I could easily toss off my Jewishness and present my auburn hair as a product of Celtic descent, my brown eyes and pallid features as vaguely European. They may well be. But there is something inside of me I can’t get rid of. It is not belief. It is not faith. Yet it weighs me down at the center of my body like a little stone, an artifact buried in my gut, reminding me of the generations of unimaginable pain and loss that was given in exchange for my existence, an existence that would forever question its own validity.

All this plays out in a nanosecond before I answer any question about Gaza. On the one hand, I see what is to me a purposeful and targeted genocide by a murderous and corrupt Netanyahu regime; that any ethnoreligious state is in direct conflict with democratic ideals, no matter how many people take to the streets of Tel Aviv; that conquerors and colonists will never have rightful claim over a land and its people, even if some of those conquerors and colonists have been there for centuries; and that there is no such thing as divine right.

This all seems clear and unequivocal to me.

But there is also, simultaneously, the fear of even asking for preservation. It is a familiar fear, burnished and kept hidden in the body of every Jew.

Alex Dezen is a writer, songwriter, and graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He fronts The Damnwells, a cult-favorite indie rock band, and coedits Nulla, a journal of literature and art. His fiction has appeared in The Masters Review and more.

Published May 2025