ON BEING TORN

Reflections on Tati Nguyen’s ‘Displacement’

BY SALMAN AKHTAR

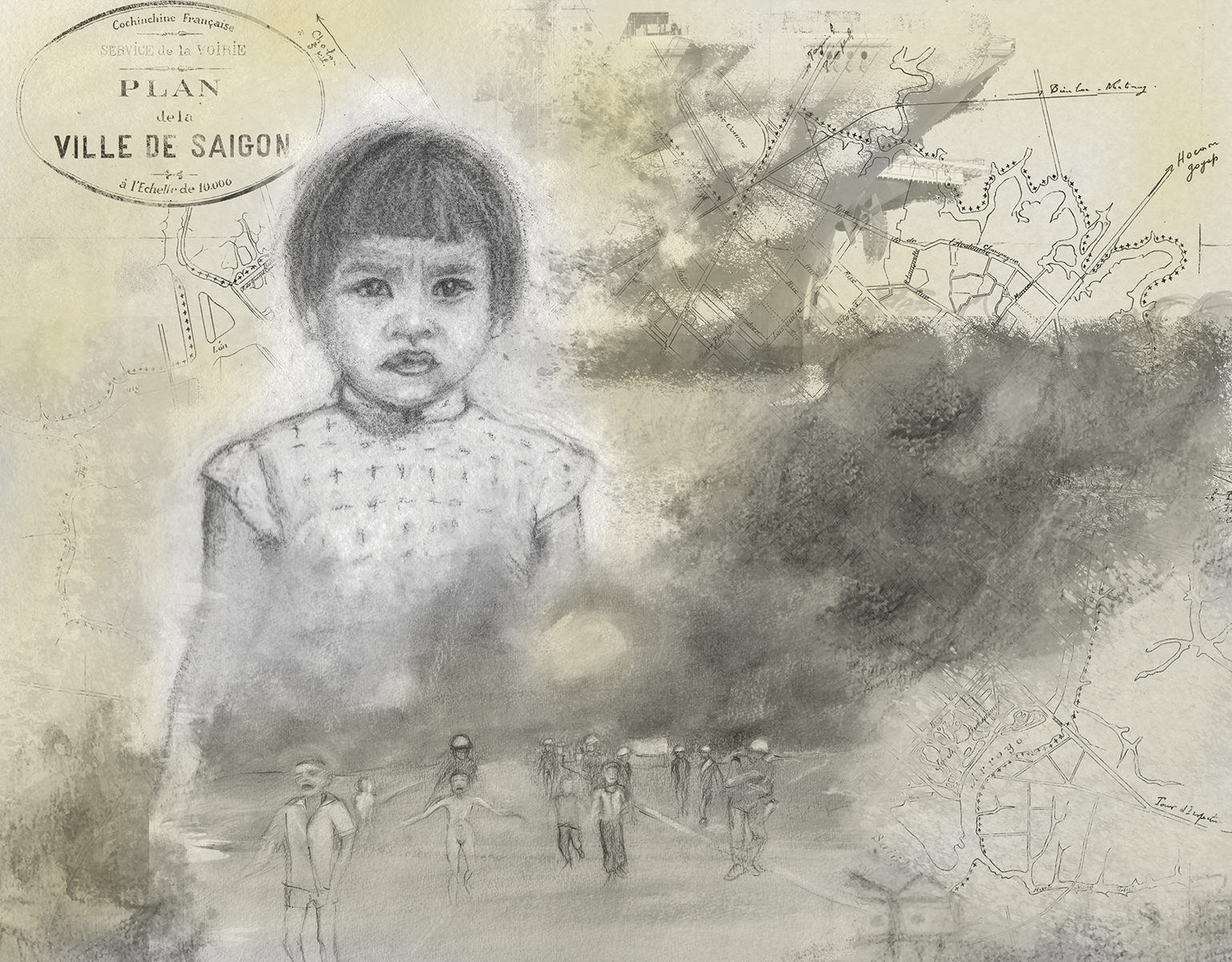

ILLUSTRATIONS BY TATI NGUYENTati Nguyen’s recollection of her clandestine, frightening, hurried, but life-saving migration during the 1975 fall of Saigon shatters me into pieces. My generally good-hearted and kind self gets flooded with pain, horror, and confusion. My immigrant self knows the anguish of geo-cultural dislocation and nods in agreement with Nguyen. But that self also contrasts my voluntary exit from a mostly serene India with her involuntary and terrifying escape from a war-torn Vietnam; it makes me feel ashamed of my occasional indulgence in masochistic glorification of my losses. And then there are my writer and psychoanalyst selves. The former admires Nguyen’s craft, tries its best not to envy. The latter refuses to be gullible. It questions the reliability of the author’s memory and also wonders how her early psychic development could have colored the processing of this highly traumatic event. However, the same psychoanalytic self warns me against the unethical nature and erroneous results of such “wild analysis.” I am torn into pieces.

As soon as I utter these words, I realize that being torn and the mental pain (Seelenschmerz in Freud’s phraseology) it brings are what all this is about. Tati Nguyen, a New York–based visual artist and filmmaker, offers us a narrative of her abrupt uprooting from the city of her origin—a city in flames, having fallen to the enemy in the final moments of a decades-long conflict. The author is all of eight years old at the time of this psychosocial amputation, and themes of being torn apart abound in her narrative. Let us take a look.

“We actually never leave our childhood homes. we carry them in our hearts till we die ... we try to replicate them, frequent them in dreams, and allow them to house the poems we write late at nights.”

I. Being torn from one’s motherland

Nguyen’s piece opens with the stunning declaration, “I was born in a place that no longer exists.” How terrible is that? How unmooring of the self and its grounding in a familiar ecological surround? Today, most psychoanalysts take living in a country for granted. The Jewish émigré analysts, dispersed all over the globe following the Holocaust, did not address their dislocation for a long time. It was too traumatic, and they did not want to call attention to their ethnicity and religion which had led to their persecution in the first place. Blocked (externally and internally) from the possibility of return, they had a pressing need to assimilate. It was with passage of considerable time and a growing sense of safety that they began to address such issues. A major impetus to psychoanalytic writing about geo-cultural dislocation (involving changes in landscape, climate, architecture, vegetation, little and big animals) came from less traumatized immigrant analysts (e.g., Leon and Rebecca Grinberg, César Garza-Guerrero, and myself) who had left their countries on a voluntary basis. One can speak of these things only when one is ready to speak. Nguyen has now given her experience a voice by addressing, in a sensitive and erudite manner, her loss of what Heinz Hartmann called an “average expectable environment”—a stable home conducive to normal childhood development.

II. Being torn from one’s home

In his inimitable fashion, Winnicott said that a home serves many emotional functions which become evident only when the home is lost. Nguyen’s memory of packing and repacking suitcases to take as the family was leaving poignantly describes the hapless effort of migrants to take their home along with them. At the end of her essay, she refers to bags that still contain photographs brought from those early days. Look, the American saying that one cannot go home again and the Spanish journalist Maruja Torres’s phrase “the wound of return” might be correct—we cannot return to an earlier phase of life, or a prior homeland, and experience it as we remember it because both we and the place have meanwhile changed considerably—but it is also true that we actually never leave our childhood homes. We carry them in our hearts till we die. We revisit them for what Samuel Novey termed a “second look.” We try to replicate them, frequent them in dreams, and allow them to house the poems we write late at nights.

III. Being torn from one’s love objects

Nguyen’s description of being separated from her beloved nanny is truly difficult to read; it is simply too painful. Her weeping, wailing, screaming, clutching doors and walls, refusing to leave, and having to be lied to by her parents are unfortunately familiar to me. At age fourteen or fifteen, I witnessed a seven-year-old cousin being brutally separated from his nanny and sent away to an out-of-town British-run boarding school. Call the scene “A Child Is Being Separated,” if you will—a scene eerily similar to that described by Nguyen. My familiarity with the significance of childhood nannies is also derived from the lives of four great psychoanalysts (Freud, Ferenczi, Bowlby, and Bion) who were deeply affected by this relational bond, its rupture showing up in subtle and not so subtle ways in their theoretical formulatio

IV. Being torn from one’s childhood innocence

A child needs safety, security, and environmental continuity for psychic growth and maturation. Such “holding” and “containing” provisions help the child negotiate its epigenetically unfolding developmental tasks. Oral clinging, anal retentiveness, and oedipal defiance notwithstanding, there is still a quality of innocence to childhood, a wide-eyed wonder that is most marked in the latency years. War, societal turbulence, and other life-threatening circumstances—with overwhelmed and scared parents—rob the child of such innocence. The “protective shield” is lacerated, trauma results, and long-term effects (e.g., flashbacks, psychic homelessness) ensue. Nguyen delineates all this in searing details.

V. Being torn from one’s right to a self-earned identity

Under normal circumstances, identity evolves from a gradual internalization and discerning synthesis of significant objects of one’s formative years (e.g., parents, older siblings, grandparents, neighbors, schoolteachers). Such accretion is mostly unconscious and ego-syntonic. It is “owned” by the individual (e.g., “I am a proud parent of two wonderful kids,” “I am a nurse”). Under abnormal circumstances, the individual is assigned labels by others (e.g., “colored,” “terrorist,” “alien,” “foreigner,” “deplorable,” “woke”). This is a subcultural theft of the individual’s privilege of self-definition. It causes estrangement on both interpersonal and intrapsychic bases. Note how the Bulgarian émigré Julia Kristeva speaks of an immigrant’s mother tongue hiding inside him or her as a handicapped child tucked away in the back room of the family house. It is painful.

Lest the scenarios I have outlined seem unbearably dismal, allow me to add that all is not doom and gloom. Trauma is a double-edged sword. Human beings can get hurt, but they also possess perseverance, stoicism, grit, and resilience. “Being torn” is certainly a wound, but a wound can turn into a scar and a scar into a story. And it is at this juncture that creativity enters the picture. Creativity, according to Freud, is “a continuation of, and a substitute for, what was once the play of childhood,” a play that, we might add, gets at times cruelly aborted. The artist and the writer—and Tati Nguyen is both—can jump-start the process of thwarted development by her healing paintings and words. This is what Georges Braque meant when he stated that “art is a wound turned to light.” Nguyen has brought much light to the exiled and ethno-dystonic parts of our selves. Bravo! ■

Salman Akhtar, MD, is a professor of psychiatry at Jefferson Medical College and training and supervising analyst at the Psychoanalytic Center of Philadelphia. He received the Sigourney Award in 2012 and is the author or editor of 110 books.

Published in issue 57.3, Fall/Winter 2023Displacement

TAP marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War with an exclusive personal account of the flight from Saigon, from the perspective of an 8-year-old girl

BY TATI NGUYỄN

Illustration by Tati Nguyễn