What School Are You?

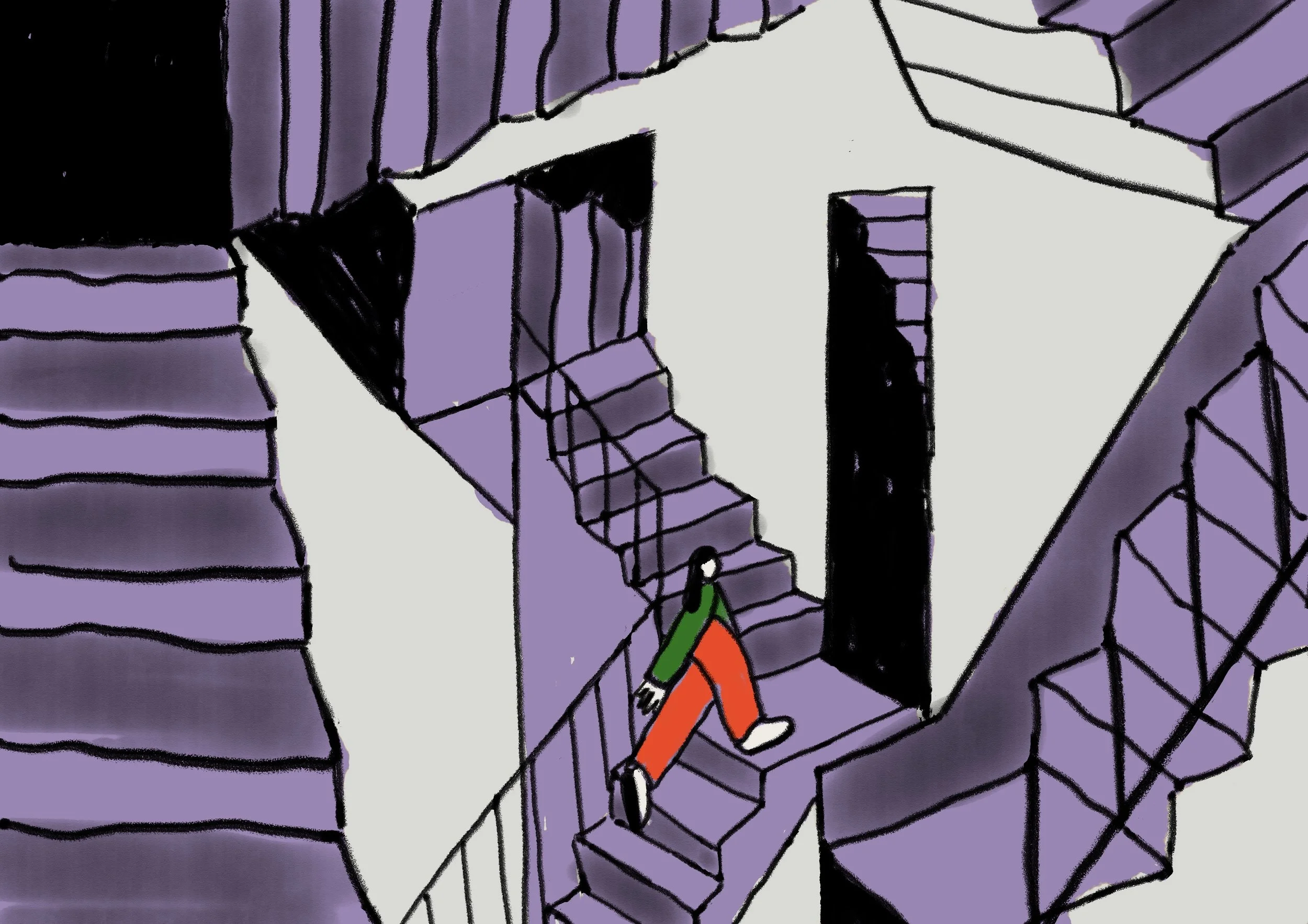

A candidate reflects on theoretical identity

By Xiaomeng QiaoIllustration by Andrea Bojkovska

“What school are you?”

By my second year as a candidate, I’d had enough of that question.

The question kept coming from peers. My frustration wasn’t with the curiosity, but the assumption: that theoretical orientation defines you, that you had to pick a team.

I found this ridiculous. Still do. But I’m in my third year now. I’ve stopped fighting it and started wondering about it instead.

My training has been plural: three American institutes, Tavistock in London, doctoral work at the Boston Graduate School of Psychoanalysis studying psychoanalysis and society. I’ve been learning with P-HOLE, a collective of queer, trans, and BIPOC analysts, and I was in the first cohort of the Community Psychoanalysis Project. The multiplicity of perspectives I’ve been exposed to in this training keeps pushing me to ask: What does theoretical loyalty actually mean?

As a more senior candidate working in China, I notice junior candidates asking about schools before they’ve learned the basics. How can you understand self psychology without Freud? Without ego psychology? How do you grasp the relational turn without knowing what it’s turning from?

This past year I’ve been translating a book of letters from analysts worldwide to candidates. Nearly every writer emphasizes one thing: Think from multiple perspectives. But our field simultaneously demands we think in splitting terms. We build more walls than bridges, as analyst Estelle Shane once said. Why confuse candidates with so many theories? Because human nature is that complex.

Why We Fragment

Here’s what we don’t say out loud enough: These theoretical battles are really about identity. About hurt, splitting, pathology, trauma passed down through analytic generations. A professor once put it plainly: “School wars are identity wars dressed up as idea wars.”

Theorists work from their own wounds and gifts. Think about Freud, Jewish and locked out of universities, his work dismissed as unscientific. That exclusion became the soil of psychoanalysis itself: a theory born from the margins, alert to repression and the costs of belonging. Kohut invented self psychology from his narcissism. “The Two Analyses of Mr. Z” barely hides its autobiography. Klein made everyone face harsh truths because she couldn’t stand comfort. Reductive? Sure. But true enough. We start by understanding our own experience.

Our clinical experience plays a role. We see a few different patients—and critically, few of them. Our sample size is tiny. Long-term work means forty or fifty people over a career, not hundreds. Much of our theorizing grows out of this narrow clinical experience, even when we imagine we’re speaking universally. When Kohut and Kernberg disagreed about narcissistic personality disorder, maybe they were describing genuinely different presentations from different settings. That is, maybe they were both right, but they were describing different populations. When we argue about technique, we might be arguing from fundamentally different experiences. The field looks like blind men and an elephant. Each school grabs one true thing and mistakes it for everything.

We’re also shaped by culture. What we now call “American” ego psychology was shaped by émigré analysts—many of them Jewish—who brought the trauma of exile into their work. But America added its own layer: a faith in adaptation, progress, and self-making. The result is a theory that, to some extent, carries both the wounds of displacement and the confidence of a new empire. I’ve always been suspicious of that adaptation piece. I’m glad Lacan pushed back, even if I don’t follow him all the way. Self psychology and relational work emphasized empathy and collaboration, mapping onto broader shifts around equality and power in the 1960s and 70s. British analysis stayed close to Klein and early development. Lacan weakened the ego and centered subjectivity—very French, very existentialist. I’m increasingly bringing society and culture into my clinical thinking. Once you stop denying that we as analysts affect our patients, it gets harder to deny that social and cultural forces shape all of us. Many of the wounds we see are not only personal but cultural, produced by histories of exclusion that demand adjustment rather than change. To work analytically is also to stay aware of these layers, the biological, the individual, the social, and to recognize suffering that exceeds the individual frame.

Times change, patients change. The problems analysts meet evolve with culture. Kohut moved from the “guilty man” of classical analysis, who is burdened by forbidden wishes, to the “tragic man” of a later era, who is fragmented by developmental deficits and failures of empathy, because he was treating patients who were no longer driven by guilt but by emptiness and collapse. Klein, in turn, built methods for borderline and psychotic patients. Contemporary relational analysts absorbed feminism, power analysis, reflexivity. The silent analyst behind the couch gave way to someone face-to-face with their patient, reflecting a wider cultural move toward dialogue and transparency. The authority once hidden in silence was now expected to speak. Good riddance.

The field looks like blind men and an elephant. Each school grabs one true thing and mistakes it for everything.

What’s Really Going On

But here’s where I’ve been landing lately, past the practical explanations: Theoretical diversity points to something fundamental we can’t quite pin down. Almost Hegelian, the way each school needs its opposite to exist. Thesis spawns antithesis, you get synthesis for a minute, then it starts over.

This pattern shows up in psychoanalytic history. Relational psychoanalysis emerged as a third track in some institutes, carving out space between existing approaches. The British Middle Group of Winnicott and company formed between the Kleinian and Anna Freudian camps, occupying ground neither extreme could hold. New schools don’t replace old ones. They’re born from the friction between them.

This dynamic between psychoanalytic schools and institutions plays itself out in the inner world of the analyst. Our theoretical commitments track our countertransference struggles. They map our ambivalence about human nature itself.

Consider projective identification, where a patient projects unwanted parts of themselves onto you and treats you as if those parts were yours. I’ve started thinking about projective identification as water flowing through my body. I’m always oscillating between two states: Sometimes I can’t hear what my patient is saying, can’t reach them empathically, because I’m resisting being projected into; other times I’m drowning, overidentified, totally submerged in it. Only after moving through both extremes can I find space to actually think. I have to go from refusing the projection to being flooded by it before I can metabolize it.

Moving through different theories feels similar. Each school speaks to the same underlying struggle with the countertransference from a different angle. When I can’t manage my countertransference, when I’m overwhelmed, I go Kleinian. I try to deliver the “right” interpretation, the insight that’ll cut through everything. Even while I’m doing it, I know I’m acting out. Robin Cohen, one of my teachers, commented on my thoughts about this. She goes the opposite direction. When she’s flooded, she becomes a self psychologist, offering easy empathy because it’s safer.

We move between positions because the tensions won’t resolve: conflict versus development, unconscious versus trauma, individual versus social structure, insight versus relationship. We can’t hold all of it at once. The schools represent different strategies for managing what we can’t fully grasp.

A supervisor once told me he’s a completely different analyst with different patients. Any decent analyst is. In practice, analysts from supposedly warring schools often work more similarly than differently. When we theorize, we’re pumping up differences to shore up group identity. Basic narcissism of small differences.

This is why school wars won’t disappear. It’s not a problem to fix. It’s built into the work itself.

And it’s why we need to stay alert to our own transference to theory—our psychic investment in the abstract models we adhere to. I notice this in myself and others. Kleinian analysts often seem more aggressive in their interpretations. Self psychology practitioners can lean toward being overly supportive, “nice” in ways that avoid confrontation. These aren’t just theoretical differences. They’re identifications with theoretical approaches, countertransference patterns disguised as technique.

Such identifications are powerful and serve multiple purposes. We need to stay reflective, alert to when we’re using theory as a shield rather than a tool. Any theory can be used defensively. Even when you disagree with an approach, you have to understand it deeply to know what you’re disagreeing with. Dismissing a school without grasping it is just another defense.

Living with It

So what do we do?

First, stop expecting resolution. School wars grow from our struggle to understand human complexity, our countertransference trouble, our need for professional identity in a field treated as half-legitimate. The ambivalence is the thing itself.

Second, notice that “What school are you?” is usually transference showing up early. A fantasy worth exploring, not answering straight. When candidates seek specific schools, perhaps training analysts and supervisors should get curious about the wish instead of just making referrals.

Third, watch how you use theory, not just which one you use. Is my Kleinian interpretation helping my patient face something real, or is it dumping my anxiety into the room? Is my self psychological empathy corrective, or am I playing out rescue fantasies? Theory isn’t inherently dangerous. Using it without reflection is.

When analysts work in genuinely plural spaces, such as training groups, supervision collectives, or international settings, something loosens. Multiple perspectives arguing productively, and you can finally appreciate what each tradition offers, even ones you once rejected.

The real work isn’t picking a school. It’s finding your own voice, something every institute encourages in theory, though institutional structures often make it difficult in practice. It’s learning to listen: to what your body’s telling you, to what’s happening between you and your patient now, to what this particular person needs this particular moment. One supervisor’s question stays with me: Are we talking about trauma or play to help the patient take hold of something, or overwhelming them with more than they can metabolize? Listen to what’s occurring.

Different theories fit different moments: different patients, different treatment phases, different cultural contexts. In my work in China, self psychology addresses narcissistic wounding from rapid social change; Kleinian work helps with early trauma and borderline presentations; relational approaches speak to concerns about power and equality. Different routes toward helping people suffer less.

Where This Leaves Me

I hit my limit with school loyalty questions in my second year. But I’ve figured out why they keep coming. We ask “What school are you?” because we’re anxious. About competence, about doing this impossible work right, about belonging. The schools offer something to hold onto.

If you listen to psychoanalysis the way we listen to patients, our splits start looking symptomatic. As psychoanalysts, we all know splitting is a problem. It’s what we help patients work through. Yet here we are, organizing around divisions we’d pathologize in anyone else.

But good analysts aren’t defined by schools. They’re defined by whether they can stay present with patients, sit with not-knowing, learn from the people they’re meant to help. Psychoanalytic multiplicity isn’t a problem waiting for solution. It’s a mirror showing us the multiplicity in human nature, in ourselves. Our job isn’t to resolve it but to work inside it, carefully, without pretending we’ve got it figured out.

Xiaomeng Qiao is a psychoanalyst in training, researcher, and Buddhist creator exploring mental health, identity, and cultural intersections; writer of Negotiating with My Ghosts and researcher on Chinese Psychoanalytic Scene.

Published November 2025