BEYOND IMMOLATION AND INFIGHTING

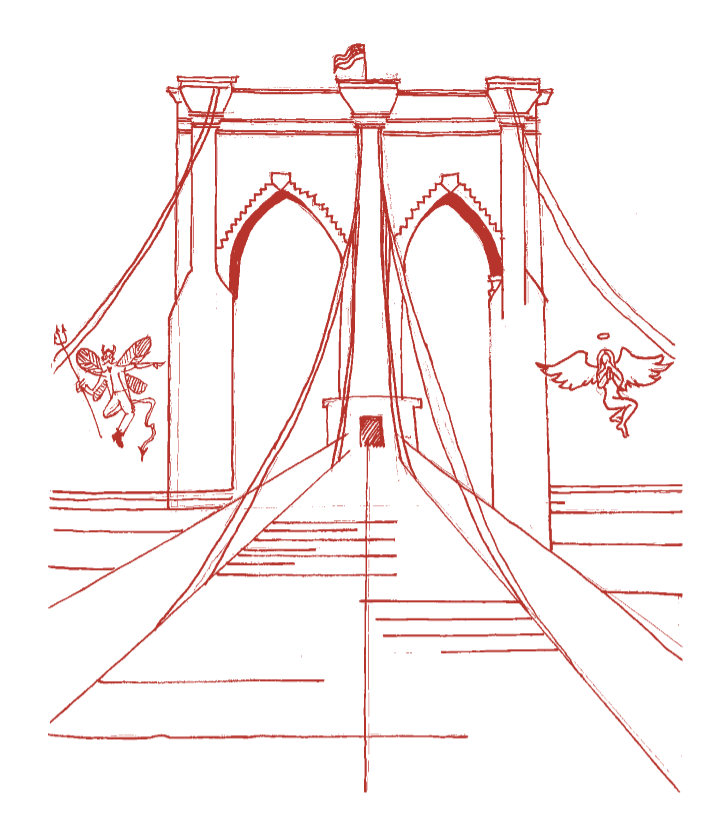

WRITTEN & ILLUSTRATED BY AUSTIN RATNERWalk through Brooklyn Bridge Park on a summer Sunday and you see people with dark skin and people with light skin and every shade in between. The Statue of Liberty stands out there behind them in the Harbor, overseeing the melting pot she’s helped create and fill. You hear Spanish, English, Chinese, and languages you don’t recognize. You see women in hijabs, in spandex, and in saris. Everybody eats the same ice cream. Everybody’s children play in roughly the same way, running ahead of their parents. I’ve wanted these first two issues of the new TAP to be like Brooklyn Bridge Park—diverse and unifying, full of life. Psychoanalysis, the science of feelings and experience, is about what is both unifying and diverse in us. Feelings are universal, but our experiences and sensitivities differ.

That was obvious in the fighting that erupted in APsA this spring, the climax of an upsetting conflict The Guardian described as a “war tearing psychoanalysis apart.” Reproaches and outrage led to a cascade of resignations. The task of publishing a tapestry of harmonious diversity suddenly looks a lot more complicated.

Psychoanalysis teaches us that what forms an indelible part of history, but is not able to be brought into consciousness, often breaks out into the open in the form of action. This makes all discussions about racism highly vulnerable to enactment.

- Final Report of the Holmes Commission on Racial Equality in American Psychoanalysis

Diversity takes work. The Holmes Commission did some of that critically important work in a Final Report that looks through the periscope of psychoanalytic reason into a sea of tempestuous feelings churned up by deep currents of racism. From the decks of a vessel itself submerged in those waters, the Report explains why psychoanalysis is indispensable to the elucidation and solution of unconscious systemic racism. For one thing, the field holds the key to unlocking the defenses that prevent us from identifying unconscious racism and talking it out. In one of many rhetorically powerful passages, the Holmes Report offers this gateway to a psychoanalytic understanding of systemic racism and the obstacles to seeing it and stopping it:

Because the deep and difficult emotional work of healing has been unequal to the wound of racism, in our country and in psychoanalysis itself, many of the thoughts, feelings, processes, procedures, and organizational structures that surround and sustain racism have been pushed out of consciousness into the personal unconscious of individuals or the social unconscious of groups and institutions. As analysts we believe, as Freud did, that what resides in unconsciousness constantly pushes up towards awareness, while contravening forces attempt to keep these unpleasant and intolerable contents hidden. Psychoanalysis teaches us that what forms an indeliblepart of history, but is not able to be brought into consciousness, often breaks out into the open in the form of action. This makes all discussions about racism highly vulnerable to enactment.

In this issue of TAP, I interview Phillipe Copeland, an African American professor of social work at Boston University, a writer on “racism denial,” and an educator at the Center for Antiracist Research. We talked a bit about “the war tearing psychoanalysis apart” in what he and I agreed was an “uplifting conversation.” He said, “Feelings and facts are not the same thing. … Our emotional reactions by definition aren’t necessarily rational. That doesn’t mean that they’re wrong, but … to deal with [emotional reactions is] not just about trying to figure out who was right in a purely factual sense.” Also in this issue, former president of APsA Bill Glover invokes the concept of “the subaltern” to help us understand the sensitivities manifest in the organization’s recent imbroglio.

The Holmes Report delineates practical remedies to stop the perpetuation of racism, beginning with psychoanalytic institutions themselves, and it models the core competency that’s needed for such work: the ability to talk about the feelings. All of them. Black feelings and White feelings and all the colors in between. Race workers outside of the field, take note; the Holmes Report offers fresh psychoanalytic approaches to the problem of racism.

ONE WONDERS to what extent a fear of annihilation played into the spring fighting in APsA. Psychoanalytic knowledge can be threatening and trigger defense mechanisms. Because of the vulnerability of this knowledge to repression, I have often argued, psychoanalysts are plagued by a chronic fear of erasure, and have long ostracized their own “dissidents” to protect their idea of what psychoanalysis should be. Freud was not immune to this dynamic and neither are we.

Death anxiety is a theme of this issue of TAP. In this edition’s Spotlight on Research, Sheldon Solomon, professor of psychology at Skidmore College, talks about the decades of research he and his colleagues have conducted on death anxiety and its attendant defense mechanisms. Their research has provided a significant source of twenty-first-century scientific validation for the Freudian theory of unconscious defenses. And it’s given rise to a kind of corollary of psychoanalytic defense theory called Terror Management Theory, which has begun to be applied to end-of-life care and in public health settings. Psychoanalyst Elisa Cheng, meanwhile, writes more intimately and personally on death anxiety in the context of parenting and psychotherapy, and TAP’s managing editor and in-house philosopher Lucas McGranahan reminds us of the benefits of ephemerality when it comes to suffering—“this too shall pass”—in a fascinating essay on the cross-connections between Buddhist meditation and psychoanalysis.

In Arts and Culture, TAP continues to expand its retinue of professional writers and artists to help spur renewed interest in psychoanalysis. Matt Gross, former author of the New York Times Frugal Traveler column, writes on the masochism of chili peppers, and Craig Harshaw explores the varieties of male masochism in cinema; Chukwudi Iwuji, one of the stars of the latest installment of Guardians of the Galaxy, helps us dig into the psychology of the supervillain; and Mitch Moxley, former executive editor of Maxim, explores themes uncovered in his psychoanalysis that he’s applied in the writing of a play about the late Anthony Bourdain, with whom he worked. Vera Camden, psychoanalyst and literature professor, and her colleague Valentino Zullo, literature professor and analytic candidate, share an essay that not only elucidates self-conscious moments of storytelling in Homer’s Odyssey, but demonstrates that psychoanalytic psychotherapy is, in part, a literary method in which patients hear their own life stories narrated back to them in a form that engenders self-sympathy.

In Stories from Life, poet Malcolm Farley writes movingly about the failure of his psychoanalyst to appreciate the social context of his teenage woes back in the 1980s—he was badly bullied for being gay—and psychoanalyst John Burton offers an empathic commentary.

As I’ve said, and will keep saying, I hope these offerings bring more positive public attention to psychoanalysis. People need psychoanalytic wisdom. They need psychoanalysis to think things out clearly before intense emotions electrify into destructive action. They need help to heal wounds of the past, to stop defensively hurting each other in the present, to take care of the future with “clear eyes and full hearts” as Coach Taylor used to say on Friday Night Lights. We need psychoanalysis to care for our vulnerable children and our vulnerable planet.

I admit it saps my own morale for the cause when I see psychoanalysts with so much to offer the world transfixed by the ever-smoldering brushfires of committees that nobody outside of the field has heard of. It’s dispiriting to see mental health professionals overrun by their own sensitivities and feelings to the point of shunning their own friends and allies. Perhaps the stresses of containing their patients’ emotions every day take a toll on their peer interactions. My God, that listserv! The APsA listserv is a tinderbox where psychoanalysts seem to enjoy lighting themselves on fire like a Buddhist monk at a Saigon intersection. What is the point? The Vietnamese monk Thích Quảng Đức who actually did that sixty years ago this summer did it to draw international attention to oppression, while the listserv immolations are conducted in obscurity, apparently to spite a handful of other psychoanalysts.

If you are bored of the immolations and the infighting and want to get behind the agenda of the new TAP to advance the standing of psychoanalysis in the world, please consider a donation of any size. Our small team is working overtime at “low-bono” prices because it’s for a good cause, but we can’t meet our high standards of content and design without financial support.

Join us! The real fight is out there. “Clear eyes, full hearts, can’t lose!” ■

Published in issue 57.3, Fall/Winter 2023