VALIDATING ERNEST BECKER'S THEORY OF THE DENIAL OF DEATH

Psychologist Sheldon Solomon on death anxiety, terror management theory, and the crossroads of human existence

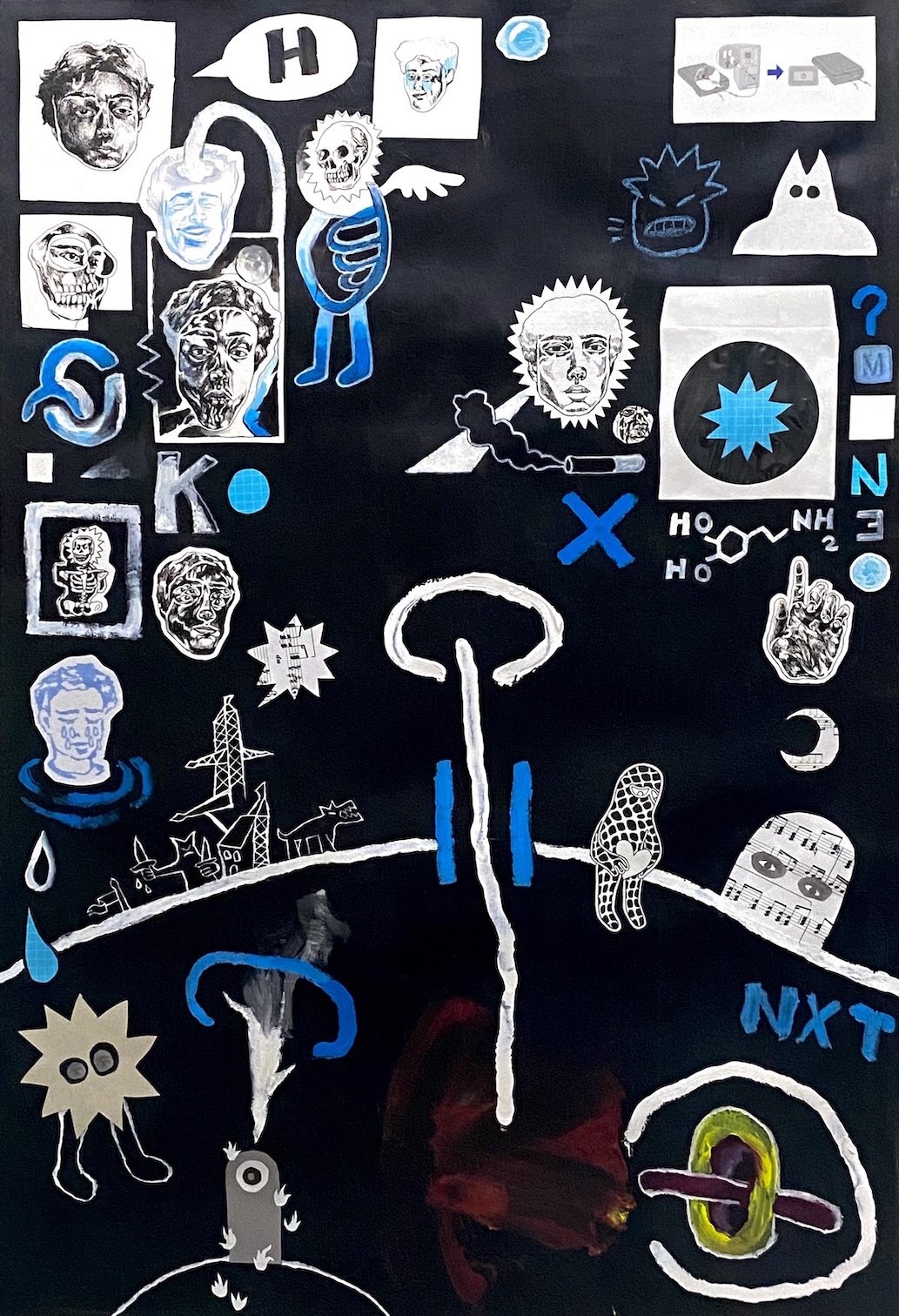

llustrations by Virgil Ratner

Nobel Prize–winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel said a little over twenty years ago that “psychoanalysis still represents the most coherent and intellectually satisfying view of the mind.” Since then, a vast body of research has accumulated in support of Freud’s core theories. One significant source of validation has come from the work of social psychologist Sheldon Solomon and his colleagues, who have spent decades conducting experiments on death anxiety and the defenses that keep it out of consciousness. TAP editor in chief Austin Ratner spoke with Solomon in the spring of 2023 about his work, psychoanalysis, and matters from the sacred to the profane. Solomon is professor of psychology at Skidmore College and author of over 150 scientific papers, as well as the popular psychology book The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life (Random House, 2015). Talking with him, Ratner says, is a little like communing with the ghosts of Socrates and comedian George Carlin at the same time. This interview has been edited and condensed.

“I realized, wait a minute, these depictions of Freud in academic psychology are ludicrous. They focus on the things that he says that I agreed are generally quite absurd while ignoring what I thought was the extraordinary profundity.”

AUSTIN RATNER: I wondered if there was anything personal about death and death anxiety for you that drew you to this sort of line of inquiry in your professional work.

Sheldon Solomon: So, I’ve been disinclined to die—ardently opposed to it—since the moment that I realized it would happen. It was around eight or nine years old, the day that my grandmother died, where my personal existential voyage began more explicitly. I knew my grandmother was fatally ill with cancer. The night before, my mom said, “Say goodbye to grandma. She’s not well.” She died the next day, and of course everyone was sad and bereaved.

I remember in the evening I was just going through my stamp collection and in the old days all the stamps had American presidents. And I’m like, “Oh, here’s George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Madison, whatever. Oh, wow, those guys are no longer here.” And then I’m like, “Oh, and my grandma’s no longer here.” And then I’m like, “Wait a minute. Let’s fast forward a bit. That means my mom is gonna get old at some point and then where’s the spaghetti and chocolate pudding gonna come from?”

Well, that was disarming. But not like the next one: oh crap, that means I’m on deck and there’s gonna come a moment at some vaguely unspecified future time when I too will be summarily obliterated. I still remember that kind of hair-raising “fuck”—I probably didn’t use profanity at eight or nine, but then again, I come from the Bronx—and I kind of buried it.

Fast forward. I get through college and graduate school, and it is literally my first week as a professor at Skidmore College where I was supposed to teach personality theory that I had no background in. So I’m like, “Oh, let me start with Freud. I’m told he’s got some stuff to say.” And at the Skidmore Library, Ernest Becker’s books are right next to Freud’s. And I see Ernest Becker, The Birth and Death of Meaning and The Denial of Death sitting right next to each other.

In The Denial of Death, the first paragraph or two, Becker says that the uniquely human awareness of death and our disinclination to accept the reality of the human condition underlie a substantial proportion of human activity—and that was a thunderbolt to my forebrain. That was the moment that I realized that my professional and personal life had become conjoined.

What I was trained to do in graduate school had little to do with any of these ideas. I read Becker, at the same time I’m reading Freud’s Introductory Lectures, and I’m just astonished. I realized, wait a minute, these depictions of Freud in academic psychology are ludicrous. They focus on the things that he says that I agreed are generally quite absurd while ignoring what I thought was the extraordinary profundity. I see [Freud and Becker] as extraordinarily compatible, particularly if we’re willing to perfuse them through the lens of some of the experimental work that we’ve done over the decades.

AR: You came to these ideas and then did decades of the hands-on, really hard, dirty work of getting funding for experiments, doing the experiments, rounding up the test subjects, developing a methodology that didn’t exist before for testing all these things and then marshalling evidence that could be presented in a persuasive way to other people. It’s a Herculean undertaking that you put on your shoulders. And now all these years later, your work is an “immortality project.” You kind of pulled it off!

SS: First of all, thanks. Basically we were just young and annoying and brash and egotistical. When we bumped into Ernest Becker and he’s like, “Oh look, the uniquely human awareness of death gives rise to potentially debilitating existential terror that we manage by embedding ourselves in cultural worldviews that give us a sense that life has meaning,” we found that so compelling that our original goal was to just spread these ideas around.

So we started giving talks and we annoyed every famous psychologist of yesteryear. I would start talking, I’d mention Freud, people would start walking out. I’d mention the word theory, people would start walking out. The point is that no one was interested. They’re like, “I never think about death, so Becker’s gotta be wrong.” We wrote a paper for the American Psychologist that was rejected with a single sentence review: “I have no doubt that these ideas are of no interest whatsoever to any psychologist alive or dead.” That same paper was rejected at every psychology journal on earth. It took almost ten years to publish.

Finally, the editor of the American Psychologist was like, “Hey, you guys are experimental psychologists. No academic in the twentieth century in academic psychology will take these ideas seriously in the absence of empirical evidence. So step up.” We never meant to do it. We just got pissed because these guys were dissing us and we’re like, “All right, let’s show these folks.” Now, there’s evidently over 1500 published studies, and most importantly, over half of them are not by us and our colleagues.

We think we’ve been an interesting interneuron of sorts that has connected the psychodynamic with the experimental community. And I do like the thought that there may be some downstream ripples based on that work. Having said that though, the older I get, I desperately yearn to get to the point where I am just as pleased when I wake up on a fine day and walk the dog around the block. We’ve planted all kinds of fruit trees around our house in what I call the Apocalypse Fruit Grove, and I’m not scratching my name on any of the trees, but I sincerely hope that they will be bearing fruit for anyone when I’m no longer around. And so I do like the idea of immortality projects—that all of us have a yearning to express ourselves creatively and uniquely—but I’m also interested in broadening the scope of what matters, because I think we live in a difficult time right now in our culture where we unfortunately teach our kids that the only thing worth doing is what you’re great at. And if you’re not the best at what you do, you’re a failure.

We also opened a little restaurant. When you’re up in Saratoga, we’ll have a snack there. I’m just as pleased to be associated with good food as good ideas.

AR: I wondered if you could just comment a little bit on the reception of the work and some of the places where you see it having had effects on other researchers.

SS: It took almost a decade to publish our first theoretical paper, and that was after we had already published empirical studies. And even the empirical studies took a long time. Finally, an editor of a journal said, “I don’t agree with you guys, but I cannot explain the finding of your experiments without assuming that there’s some merit to your rather bold claims.”

We were brash, we were young. My first two talks as a psychologist were “Why Does America Cause Mental Illness?” and “The Psychopathology of Social Psychology.” I said, “Why is it that social psychologists don’t study anything interesting or important?” And my point is that we put the methodological cart before the theoretical horse. In other words, we tend to limit what we study by the available laboratory paradigms. And I was like, “Fuck that. Why don’t we start with the question and, if need be, develop the paradigms that will enable us to explore them?”

“Becker says that the uniquely human awareness of death and our disinclination to accept the reality of the human condition underlie a substantial proportion of human activity—and that was a thunderbolt to my forebrain.”

So we were annoying at first, in part because the 1980s was also a time when psychologists were moving away from big, broad theories and focusing on little microscopic detail. We wrote a lot about why we disagree with that approach using a little-known guy, Einstein, the physicist who pointed out that facts mean nothing without the theoretical formulation. So we were annoying because we were advocates for a motivationally based, broad theory when psychology was talking about microscopic cognitive approaches.

And then we’re like, “Yeah, your fear of death determines or influences everything, even if you’re unaware of it.” Again, the dominant response is, “I’m not afraid of death and therefore your ideas are wrong.” Even when we started producing evidence, people were not particularly engaged. It was only when other theorists started to jump in to (a) replicate our findings and (b) more importantly, extend them. A group of Israeli psychologists—Mario Mikulincer, Gilad Hirschberger, and Victor Florian—connected, theoretically and empirically, attachment theory with terror management theory. That added a developmental twist.

To make a short story long, it took about twenty years. But over that time, we gradually became incorporated into academic psychology. You’re part of the mob, like it or not, when there’s a GRE question about your work. And then we got a little plaque from the American Psychological Association. It was very cool because on one side of us was Daniel Kahneman, and he’s won a Nobel Prize—he got a bigger plaque, and that’s right—and on the other side was Claude Steele, a famous African American psychologist who developed the concept of stereotype threat.

So, we went from basically homeless janitors to legitimate academic psychologists in two or three decades. I’d like to think that we had a little bit to do with establishing the idea that you can ponder existential questions from an experimental point of view.

I think terror management theory is in an interesting moment because it is getting much more widely known outside of academic psychology. There’s a communications program at James Madison University based on using terror management theory—what does that imply about how we communicate? There are other folks that have developed a health model of terror management theory. I’m delighted to be talking to you and other psychoanalysts. Two weeks ago I was in Japan talking to a group of palliative care oncologists, and so our work has now moved into clinical circles. Death anxiety is now being described as a trans-diagnostic construct that underlies or amplifies all psychological malaise. The people in sustainability programs are like, “Hey, we’re never going to get at taking care of the environment unless we understand the role of death anxiety in destroying it.” There’s a large literature showing how intimations of mortality influence the outcomes of judges’ and juries’ deliberation. A lot of economists are recognizing that we don’t cling to money for rational means so much as it is a thinly veiled immortality symbol. Political scientists are actively engaged with us as a result of our work, demonstrating that the appeal of populist demagogues is very much a result of existential anxieties.

AR: The notion of proximal and distal defenses is a nomenclature that is not really used in psychoanalysis that seems very useful.

SS: It’s not anything familiar to psychoanalysts—or in fact to us at the time. I want to put in a plea for why science is important. It’s not only to corroborate the merits of an idea. We started terror management theory research to just see if Becker was on the right track when he said that concerns about mortality make us embrace our particular cultural worldview. It was in trying to figure out why our studies sometimes worked or didn’t work that we realized that it matters whether you know you’re thinking about death or not. And so if I say to somebody, “Hey, tell me your thoughts and feelings about the fact that you’re gonna die,” whatever you say thereafter, death is immediately on your mind. What we have found is that that automatically instigates a process to banish death thoughts. We call it, “not me, not now.” If somebody says to me, “You know you’re standing in the road and there’s a truck coming at you,” well, I could move out of the way. That would be a proximal defense. Or if somebody says, “Hey, there is a pandemic coming in.” And you’ll be like, “Well, I’m going to make an appointment and get vaccinated.” That’s a rational proximal defense. On the other hand, if we were in my office, I could push a button and the word “death” would be flashed on the computer screen for 28 milliseconds—so fast that you wouldn’t know that you’ve been exposed to it. Well, that instigates a completely different set of responses that are more geared towards maintaining self-esteem and confidence in one’s belief systems.

Let me give you an example. If you tell somebody in Florida that they’re gonna die, and then you say it’s a bad idea to go outside in the sun because you might get skin cancer, and then you just ask people, “When you go to the beach next, how long are you going to lay out and how much sunscreen are you going to use?” people say, “I’m gonna use more sunscreen, and I’m gonna stay out on the beach less.” That’s a proximal defense to ward off death anxiety. But if I blasted you subliminally with the word “death” so you didn’t know that you were thinking about it, people whose self-esteem is based on their appearance—because for White people at least, ironically, being tan is beautiful—they say they’re gonna be there longer and they’re gonna use less sunscreen because now it’s a defensive response to boost your self-esteem because brown or bronze is beautiful.

This is what we feel to be a major theoretical and empirical extrapolation that extends our understanding of these phenomena way beyond what Becker and other theorists ever proposed. Of course, we’ve known conscious and unconscious—everyone makes that distinction—but what this work demonstrates is that they are qualitatively distinct defensive processes that unfold in an orderly temporal progression as a function of the degree to which you’re aware that death is on your mind. And we think that’s been a big addition above and beyond just saying, “Oh, Becker’s right here and he’s right there.”

AR: So, proximal defenses push death anxiety out of consciousness. Distal defenses are unconscious. They are more irrational and more emotional and are designed to keep death unconscious.

SS: You have it exactly right. To me, any psychoanalyst should be delirious to look at this work.

AR: I look around at what I sometimes refer to as an urban legend that Freud has been completely discredited. And then I look at your work and how much data it presents in support of the notion of defenses, one of the pillars of psychoanalytic thought. It just seems to me extremely important that people know about this branch of the evidence base for defense mechanisms.

SS: No one denies right now that we are very likely at the crossroads of human existence. And yet I see very little reference in popular discourse to this very existential psychodynamic historical approach, without which I think you can understand almost nothing. Not saying that these ideas by themselves will suffice, but to pretend that what’s happening now—the fascism, the xenophobia, the psychological disassociation, this pervasive dis-ease—to not see that as a massive individual as well as collective defensive reaction to literally being marinated in existential anxieties, it’s anal-cranial fusion. It is a denial of the one point that we should be starting with as the foundation for an understanding of our present concerns. ■

Published in issue 57.3, Fall/Winter 2023