CLEOPATRA'S DREAM

On the uses of fantasy in the work of Shakespeare and Freud

Written & illustrated by Austin RatnerIllustrated by Austin Ratner

Sigmund Freud and William Shakespeare go together like peanut butter and jelly. It’s rare to find a Shakespearean who’s not at least a little bit Freudian and perhaps even rarer to find a psychoanalyst without an interest in the Bard. Shakespeare scholar Leonard Barkan provides a classic example of the affiliation between the two geniuses in his recent book Reading Shakespeare, Reading Me (Fordham University Press, 2022), in which he appeals to Freud as an “authority of, I would say, comparable talent to Shakespeare’s in mapping the human condition.” However, in “False Friends, True Loves,” Barkan’s delightfully cheeky essay in this edition of TAP, he questions whether Freud and Shakespeare always stride together in perfect lockstep. Mapping the human condition was, after all, not Shakespeare’s only aim. Freud sought to understand human character in order to treat its maladies. Shakespeare studied it in order to create characters onstage.

And sometimes, Barkan suggests, the Bard did not even want us to believe in his characters, let alone understand them. In his late-career play Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare flaunts his characters’ constructedness and his own artifice: the identities of Antony and Cleopatra swirl and change in a windstorm of words. There are more speeches in this play than in any other Shakespeare play, and the characters, as Barkan shows, often expend their wind on contradictory accounts of themselves and others. Shakespeare went postmodern in the end, Barkan concludes, playing with the idea that human character is unknowable or a mirage woven from raveling strings of words. French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who looked into the human heart and saw a lack, or at best a tornado of flying receipts and paper bags, would probably approve. Freud would not. The Ur-analyst suggested that repression obscures the self, not that repression erases it, and aimed psychoanalysis at recovering self-knowledge. Likewise, in many of his greatest plays, Shakespeare wrote psychologically comprehensible characters who act predictably and consistently even as they sometimes blind themselves with desire, guilt, and fear (“art thou yet to thy own soul so blind?”), and even as they sometimes grow, discovering new aspects of themselves.

So what is Shakespeare doing in Antony and Cleopatra? Is he perhaps taking a new tack with an old theme, evident elsewhere in his works, that hidden motives render the self mutable and mysterious? Professor Barkan has other ideas. He observes, for one thing, that in Shakespeare’s later works “fantasy and fairy tale will substitute for the densely represented interior life.” By 1611, when Shakespeare writes his farewell play, The Tempest, he will take us to magic realms beyond science but also far beyond the lugubrious beanfields of postmodern doubt—to the domain of a conjurer, a place of lucid dreaming.

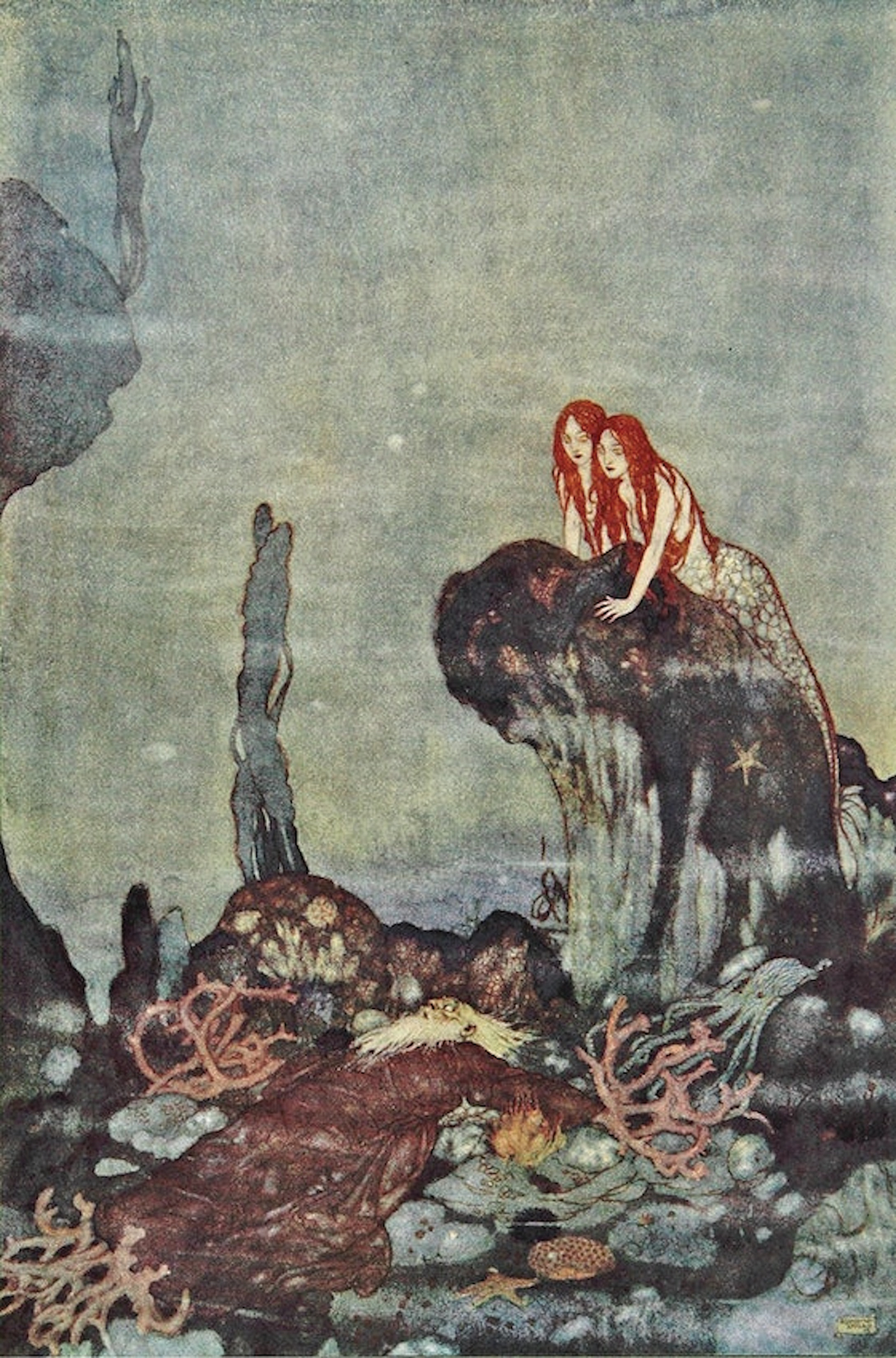

“Full fathom five...”

by Edmund Dulac, Hodder and Stoughton’s

The Tempest, 1915.

Both Freud and Shakespeare had much to say about dreams, and they evidently shared certain impressions of the nature of dreaming. For example, Shakespeare anticipates Freud’s theory of dreams as expressions of wishes. Freud famously used Moritz von Schwind’s 1836 painting The Prisoner’s Dream as the frontispiece to his Introductory Lectures to illustrate this point. Schwind’s painting depicted a recumbent prisoner dreaming of escape through a high cell window. Likewise, in Shakespeare’s Richard III, the Duke of Clarence dreams of escape from the Tower of London, where he’s imprisoned and sentenced to die. Clarence narrates his dream: “Methoughts that I had broken from the Tower / And was embark’d to cross to Burgundy.”

Freud and Shakespeare also shared the idea that fictional art is a waking dream shared by artist and audience. Shakespeare equates dramatic art with dream, for example, when Hamlet berates himself for failing to take action and compares himself to a traveling actor who summons so much activity and feeling “in a fiction, in a dream of passion.” Freud links art and waking dream in his 1907 lecture “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming.” In this view, both Shakespeare and Freud rooted themselves in classical tradition. The ancient Roman Cicero reserved special honors for what he called illustre, “that department of oratory which almost sets the fact before the eyes.” In an essay called “The Argentine Writer and Tradition,” Jorge Luis Borges would later call it “that voluntary dream which is artistic creation.”

Where Freud mined dreams for information about the psyche, however, Shakespeare wielded them as instruments invested with a power so great it could grant the artist control over his audience or make a dreamer feel immortal. The Duke of Clarence’s dream in Richard III is not only a dream of escape from prison but from death. He dreams his brother Richard knocks him overboard, but instead of drowning, Clarence visits wonders on the bottom of the sea, including skulls with gems for eyes “that mock’d the dead bones that lay scatter’d by.” Sir Brakenbury, Constable of the Tower, asks Clarence, “Had you such leisure in the time of death / To gaze upon the secrets of the deep?” Clarence answers, “Methought I had.” Of course, it was only a dream, and Clarence does not survive his death sentence in waking life. To add to that, his executioners drown him. In a vat of wine.

The image of death transformed to wonder in the dreamscape of the sea returns in Shakespeare’s grand finale, The Tempest, when Ariel works dreamy magic on death, singing again of sunken skulls with jewels for eyes (this time, pearls). In The Tempest, we enter the province of artistic daydreaming, of conjuration, a talent mastered by the play’s central character, Prospero. With his magical art, Prospero animates spirits just as Shakespeare animates characters in the fictional dream of the play:

“Spirits, which by mine art / I have from their confines call’d to enact / My present fancies.” He manipulates other characters with elaborate stories, just as Shakespeare manipulates his audience. Prospero’s art is so powerful it can rouse the dead: “graves at my command / Have waked their sleepers, oped, and let ’em forth / By my so potent art.” In the end, a son thought drowned turns up alive, symbolically reversing the fate of the Duke of Clarence—and perhaps that of Shakespeare’s own son Hamnet, who died. Prospero puts aside his magic arts, but their death-defying powers leave the world of the play permanently changed.

Clarence’s Dream, William Blake, 1774.

After Mark Antony dies in Cleopatra’s arms near the end of Antony and Cleopatra, Cleopatra has a dream about him in which he appears godlike and physically bigger than the world. In narrating the dream, she asserts that when it comes to creation, nature cannot compete with dreams, but in this case she wishes that it could. She wishes that Antony could really be bigger than the world, bigger than a dream, bigger than death:

But, if there be, or ever were, one such,

It’s past the size of dreaming: nature wants stuff

To vie strange forms with fancy; yet t’ imagine

An Antony were nature’s piece ’gainst fancy,

Condemning shadows quite.

She wishes her dream were powerful enough to make itself come true. It’s an impossible dream. But it’s also one that Shakespeare’s career in a sense achieves. Shakespeare asks the waking dreams of his art to rise up and defeat death for real by outlasting his physical body, even outlasting other attempts at memorial by people who in life wielded more earthly power than a lowly poet. His Sonnet 55 begins:

Not marble nor the gilded monuments

Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

This is a moment in literature like Babe Ruth calling his shot in the 1932 World Series before swatting a home run into the centerfield bleachers at Wrigley. It’s like Lebron James tattooing “Chosen 1” across his shoulders at the beginning of his career and then going on to break the all-time career scoring record at the end. (He did it this past season, his twentieth in the NBA.) Shakespeare really did in a sense defeat death and time. More than four hundred years later, he still reigns supreme. As Gustave Flaubert said of him in an 1846 letter to Louise Colet, “He is a terrifying colossus: one can scarcely believe he was a man.” By dreaming—and staging—such evocative and penetrating dreams, Shakespeare made Cleopatra’s dream come true, only the giant bigger than the world, bigger than time, was not Mark Antony, it was William Shakespeare.

When Shakespeare is in his power-dream mode, he mocks death, whether by setting gems in skulls’ eyes or by satirizing his own carnage-filled tragedies, which he seems to be doing in part in Antony and Cleopatra. It’s a little bit funny that Mark Antony falls on his sword “and misses,” as Barkan puts it. The scene where Mark Antony tries to convince his friend Eros to kill him makes me laugh out loud when I read it. Antony asks Eros to do it no less than five times, an extent of repetition seen mainly in comedy, and as in comedy, the payoff comes with a reversal of established expectations: each time Antony asks to be stabbed, Eros resists; finally, the fifth time, Eros assents but surprises Antony by stabbing himself instead! In Antony’s death scene, Antony keeps saying, “I am dying,” but he won’t die. He keeps trying to speak his last words but can’t seem to get to the point, and when he asks Cleopatra to let him speak, she interrupts him, “No, let me speak.” May we all go out with our loved ones interrupting our last words!

Antony’s death scene is funny, but it’s also profound. In it, Shakespeare’s words interrupt death. In the Bard’s career as a whole, his words in some real sense interrupt mortality. The products of his imagination still have extraordinary power. They are, as Cleopatra says, “past the size of dreaming.” ■

Published in issue 57.3, Fall/Winter 2023