Graphic Memoirs of Childhood

Star Cartoonist Raina Telgemeier Draws a New Generation

By Vera J. Camden and Valentino L. Zullo Collage by Austin Hughes. Cartoon images by Raina Telgemeier, ©Graphix.

For many, Raina Telgemeier—or simply Raina, as her readers call her—is a household name. Ask a parent of a young child if they know about her books. Nearly every parent we’ve spoken to proclaims, “Yes, and her books are on our shelves!” Or, “Yes, and my kids carry her books everywhere!” This is especially true in households with children under 16 years old, as an article in The Atlantic notes. It’s rare instance for us to meet a mother or father who doesn’t recognize the titles Smile, Sisters, Guts, Ghosts, or Drama. (Her next book, The Cartoonists Club, coauthored with Scott McCloud, is due out in April 2025). These stories are doing something for children that we think the readers of TAP should know about; her books are drawing children in even as she is, as it were, drawing them out. Indeed, these kids are not just reading these stories but are also using them to tell their own stories. Raina’s stories of latency and young adolescence, girlhood, sibling rivalry, anxiety, and trauma open doors to the interior mansions of the children’s own imaginations and creative capacities.

In February 2025, Raina will join the national meeting of the American Psychoanalytic Association for a live interview as the artist/scholar-in-residence, hosted by APsA’s Academy Committee. We are honored to welcome Raina to our gathering in San Francisco as we follow what Freud taught us: that analytic insight comes from stories of all sorts, sizes and styles.

This is not the first time comics and psychoanalysis have come into contact (see Raina Among the Analysts below). But today it seems more necessary than ever to pay attention to what children are reading, so that we keep in sight those authors who are our best hope for the future.

Raina Reigns

Raina creates comics—or sequential art, as cartoonist Will Eisner calls them. This medium, which was once seen as disposable to some and immoral to others, is not only having a moment but may indeed be redefining our contemporary way of storytelling and of seeing the world. In an age of smart phones and social media, comics, an analogue form, are thriving among kids as well as adults. Slowing down time to reflect on emotional life, Raina’s books are helping kids to reflect on their experiences and the numbers prove it. Every one of her comics in the past decade has become a #1 New York Times bestseller, and her last book, Guts, had a first print run of one million copies. Millions of readers can’t be wrong, to paraphrase William Moulton Marston, psychologist and creator of Wonder Woman, writing in 1944 for The American Scholar.

Figure 1. From Smile p. 29. By Raina Telgemeier. ©Graphix

It was her debut memoir, Smile (Graphix, 2010), that put Raina on the map for the millennials and younger generations. In this breakthrough work, Raina frames the transition from child to teenager, making it recognizable and tolerable. Her story is individual (an accident causes 12-year-old Raina to lose her two front adult teeth), but her worries are universal. Namely, she worries what her friends will say when they see her braces holding in her new teeth. Her confession to her girlfriend that “I was afraid it made me look like a six-year-old” (Fig.1), backfires when this fickle friend seizes this vulnerable moment to make fun of Raina’s ponytails as the real remnant of a repudiated childhood. Raina rushes home humiliated to look in the mirror: “I do look like a baby” (Fig. 2). Such scenes are designed to capture adolescent pain with exquisite nuance. And the attuned reader, too, faces her pain: first in the confession, then in the interior conviction, and finally in the frowning face. Yet Raina does not leave us in the Slough of Despond! Her work also gives us a way out of bad feelings. As she told us in an interview for the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics,

if you’re reading a memoir, and on page four the character has a traumatic experience, you can see that there’s two hundred more pages after this in your hands. So, there’s got to be some other feelings that follow. Maybe that’s hopeful to a young reader. But you’re also allowed to stay and linger on the discomfort if you wish.

That’s an important lesson to learn when you’re a child (or even an adult)—that the feeling you have right now isn’t the one you are always going to have. And spoiler alert: Raina does smile again.

Raina documents the confusing pain of childhood in ways that can be processed by her readers because, as cartoons, they are softer, easier for us to reckon with, and they spur us to conversations about the ways we have let the voices of others into our head. To that point, Raina introduces a new voice into the minds of her readers as she begins a conversation with them. In tune with her own internal voice, she considers how her storytelling will affectively impact her readers.

Figure 2. From Smile, p. 31. By Raina Telgemeier. ©Graphix

Youth Remembered

If such comics are drawing children in, then as psychoanalysts we ought to be curious why. Raina brings into focus the inner life of the child, reminding us of the importance of what we analysts call the latency years: that in-between period in the life of the child where the world is ripe and yet often unbearably sad and confusing. This period of development is relatively overlooked in discussions of child development. Much has been written and theorized about the pre-oedipal and oedipal and of course the adolescent, but can the same be said for latency? This is one of the most intriguing stages of mental life, where we find our inspiration and a way of engaging with the world. Raina’s stories illustrate that “love affair with the world” that Phyllis Greenacre witnesses in the artist beginning in infancy and taking flight in latency, a time which “may be a time of great artistic interest and development.”

Raina’s works capture middle grade readers, those between 8 and 12 years old, because her voice resonates with the inner and outer worlds they inhabit. In conversation she has shared with us that perhaps she can capture the voice of that younger self so well because she still has the journals of her youth, which her parents saved:

I can still read what 12-year-old me was thinking. I still have access to her. I don’t know if that’s why I’ve continued to have such a good memory of those years, or if I’m able to capture the voice because I can literally still read it. Probably some combination of the two.

Recognizable on each page is the dialogue of the latency child and the early adolescent. Those children reading the books see themselves mirrored; for the adults, frankly, it can be the same. She pulls out our younger selves so that they can converse with our adult selves as we read. Thus, Raina doesn’t document childhood or give us a guidebook: Rather, she lets us bear witness to feel like her diary drawn on the page is also our own. With sparse narration guiding us, there is little distance between us and Raina, between her dialogue balloons and thought bubbles and us as readers. Her memories become our memories for a moment, spurring our associations as readers, and encouraging our reflections. That act of listening to herself plays out among millions of readers who also learn to listen to themselves, to hear their own thoughts, to think through her experiences and to reflect on their own. She draws in her readers even as she draws from her own memory, and in that shared space of the comic book page each discovers themselves in new shapes and sizes.

In Sisters, her second graphic memoir, Raina humorously depicts the childhood excitement, disappointment, and everything in between of having a sister (Fig. 3). Reflecting again on an experience of sibling rivalry, an area not frequently explored in depth in recent psychoanalytic literature, she recalls begging for a sister from her parents. And yet once she has that sister, the rivalry begins with the question, “You’re sure this is a girl?” (Fig. 4). These moments wake up the child inside of us with such recognizable questions that are so funny, but once again capture the confusion of growing up—an experience which includes getting exactly what you thought you wanted, which often ends up not being what you want at all. Again, it’s her ability to remind us that this feeling won’t last that makes it tolerable.

Figure 3. From Sisters p. 6. By Raina Telgemeier. ©Graphix

Figure 4. From Sisters, p. 9. By Raina Telgemeier. ©Graphix

If Raina can give her reader a voice it is because she learned from the best. Reading the works of Judy Blume and Lynn Johnston allowed her to find her storytelling style, her voice, her medium. She now gives others the gift of hearing our own voice as we listen to hers. She explained to us that one of the most surprising and beautiful experiences has been how these stories are not just a conversation with herself but with others:

I quickly discovered that after finishing a very personal story and thinking ‘Okay, now I don’t have to tell it again,’ [that this] isn’t true! Because a kid reads the book, and then they want to talk about it. They want to ask me questions and tell me things about themselves. So, I’ve ended up having a million conversations with a million different readers. It isn’t possible for me to converse directly with every one of them, but I can continue to have conversations with myself, and write books based on those. The role I have now is really different from where I started, but it feels like it went in a logical direction, and it’s super fulfilling. I feel like there’s a reason to get up and do what I do most days.

Raina is not writing for analysts, clearly. She makes plain in interviews that she thinks constantly about her young reader and that, as expressed above, this reader gets her up in the morning and fills her mind and heart. But she has much to offer the practitioner as she helps us to learn how to listen to ourselves, to the child within, and to listen for that part of the patient that is the child and the early teen. Hers is thus not a commanding voice but a guiding voice that moves through the ages of children and adult with fluid time and in no rush.

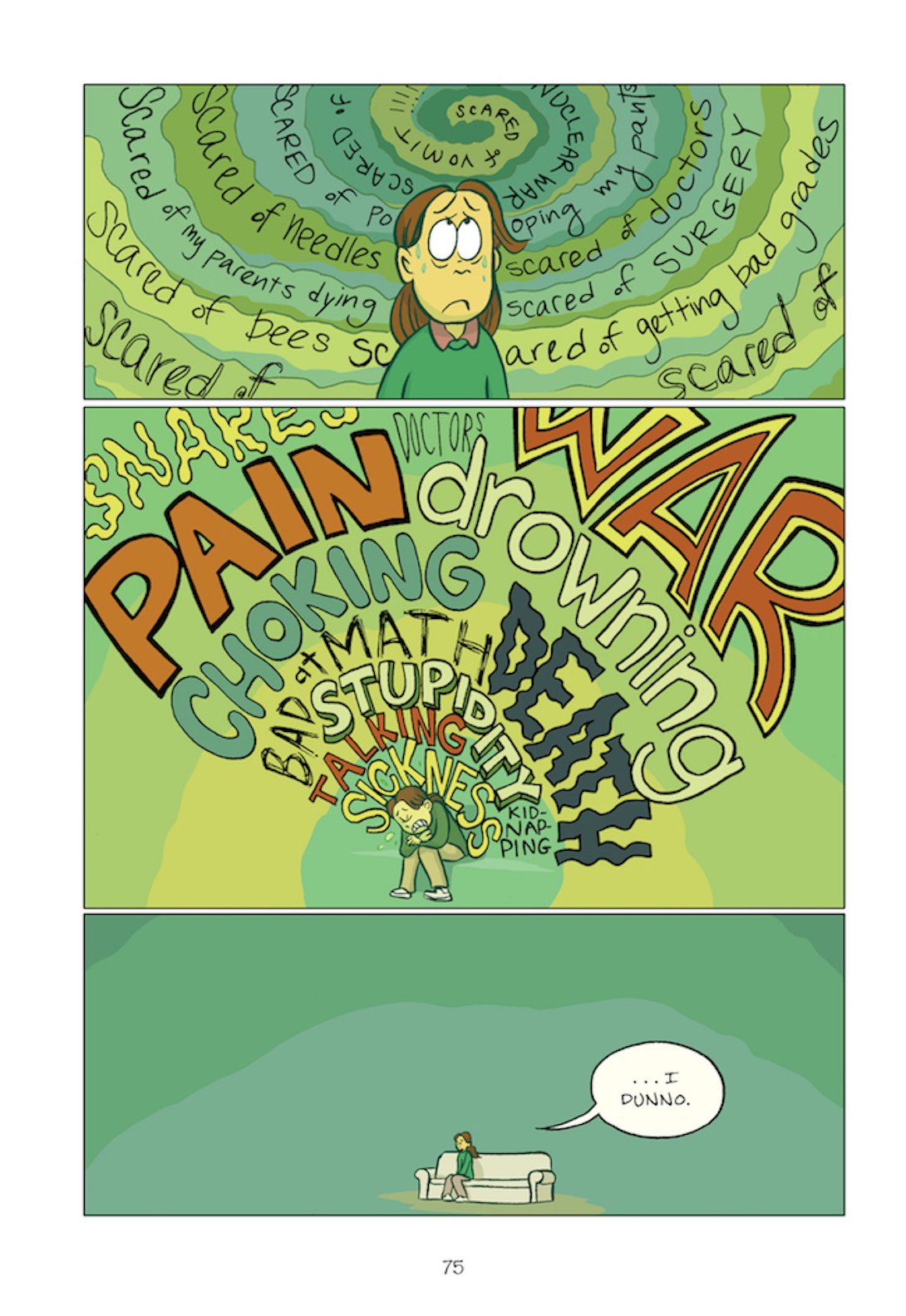

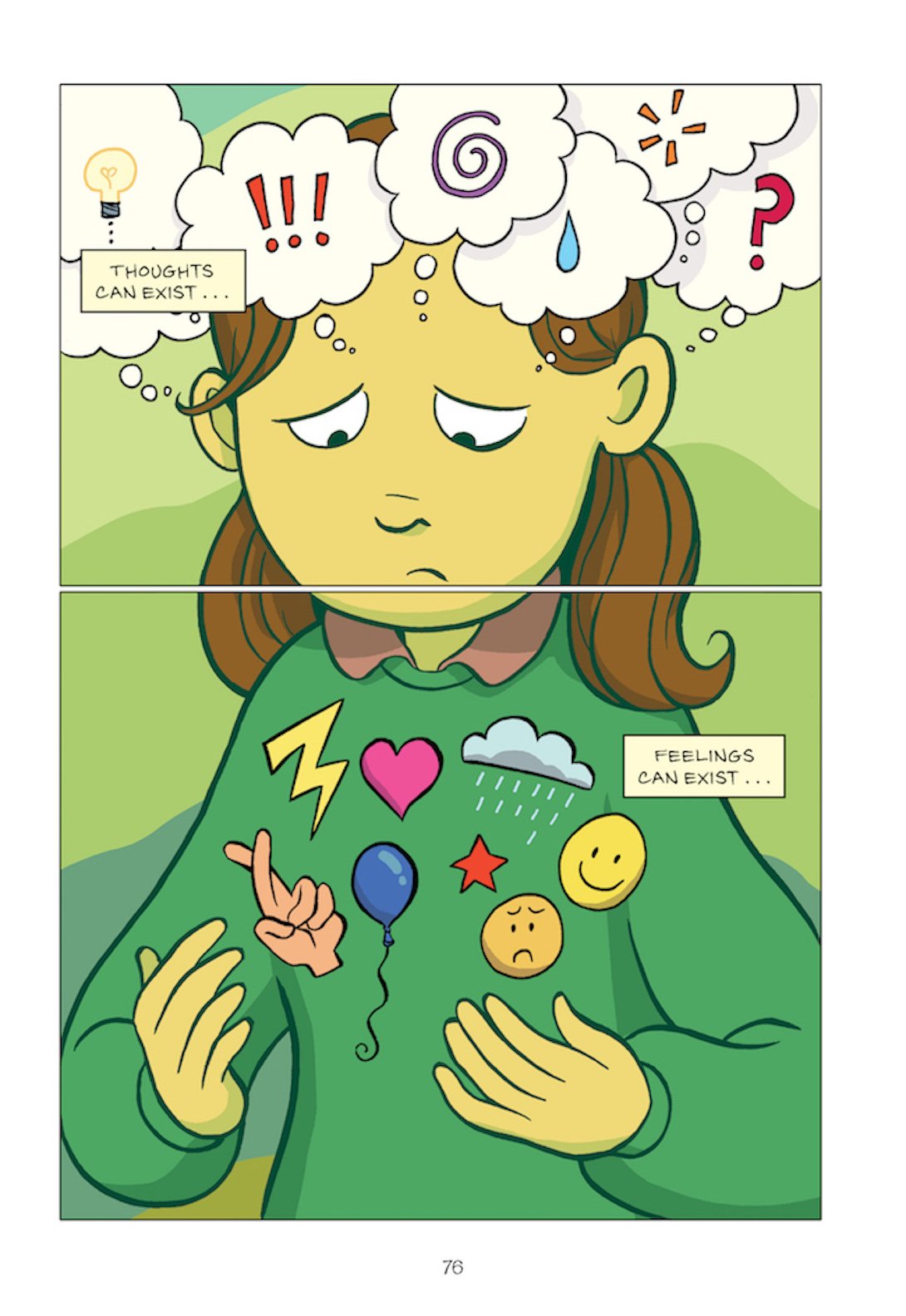

Finally, Guts, her third memoir, tells the story of 9-to-10-year-old Raina, who has a stomachache that won’t go away, leading to a diagnosis of anxiety. In this narrative, Raina most dramatically links her bodily experiences directly to her emotional states and demonstrates with simple elegance the direct line between the body and the mind that is immensely revelatory not only to the young reader but to us all. Unencumbered by diagnostic jargon, she portrays what it feels like for a young person to find their body expressing what they cannot find words to say. In a session, her therapist says to her, “So … will you tell me a little about why you’re here today? In your own words.” Raina then illustrates how finding words becomes overwhelming to her. She is confused and they start to weigh her down. Finally, looking quite small compared to the feeling that fills the room—which is unnamable, only recognizable in the color green—Raina says, “I dunno” (Fig. 5). As narrator she tells us on the following page, “Thoughts can exist … Feelings can exist…” (Fig. 6) as she depicts thought bubbles filled with images but no words. On the next page she reflects, “but words do not always exist.” Here we see an illustration of Freud’s famous comment in his case of Dora where he writes, “If his lips are silent, he chatters with his fingertips; betrayal oozes out of him at every pore.” Where words fail, Raina’s body tells a story. In images, we can see what Freud asked us to hold in mind: That which has not yet been named will take the form of an image—expressed through the body.

Figure 5. From Guts p. 75. By Raina Telgemeier. ©Graphix

Figure 6. From Guts, p. 76. By Raina Telgemeier. ©Graphix

An Invitation to Create

Raina’s cartoons appear to be simple, like comic strips from the newspaper, but Raina proves that comics allow the reader to join in imaginatively and find within this depiction ways to reimagine their own shifting and often confusing bodily states and fantasies. By depicting her own remembered experiences in this medium, Raina provides a place of identification and even consolation to the reader who might otherwise feel isolated and peculiar amidst the cacophony of contemporary culture that pushes us toward external interventions to ameliorate the familiar growing pains of youth. The visual register is not primitive or childlike but rather another way of processing information, of linking feeling and thought in ways words alone cannot achieve. Raina thus offers to her reader her portrait of the cartoonist as a young girl that invites her reader (like the masterful Lynda Barry) to take up their pencils and pens—and follow her.

Raina Among the Analysts

Freud often sought out insight from literature, even turning to children’s literature and comics. He enlisted Wilhelm Jensen’s novella Gradiva to examine unconscious motivations in dreams, named Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book as one of ten “good” books which come to mind without much reflection in a letter to Heinrich Hinterberger, and included a comic strip by Nandor Honti in his Interpretation of Dreams. Since Freud, comics and psychoanalysis have met several more times. D. W. Winnicott points to Peanuts creator Charles Schulz in Playing and Reality, Didier Anzieu famously wrote an introduction to a collection of the Belgian comic series Tintin, and psychoanalysis has been forever enshrined in comics history with New Yorker cartoons as well as the infamous production of Psychoanalysis published by EC Comics and written by Daniel Keyes, the author of Flowers for Algernon, with art by Jack Kamen. Readers may also know Alison Bechdel’s graphic narrative Are You My Mother? which depicts her psychoanalysis framed by compelling visual reflections on the writings of Winnicott, filtered through her own childhood traumas and transformations.

Vera Camden is a supervising and training analyst at the Cleveland Psychoanalytic Center, emerita professor of English at Kent State University, and American editor of the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics.

Valentino Zullo is an advanced candidate in psychoanalytic training at the Cleveland Psychoanalytic Center, an assistant professor of English at Ursuline College, and associate editor of the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics.

Camden and Zullo are coediting an issue of American Imago on psychoanalysis and graphic medicine to be published in 2025.

Published December 2024.