Mind and Body

Whatever happened to psychosomatics?

By Neal SpiraIllustration by Austin Hughes

In the beginning there were our mothers, so to speak: the five women whose stories make up the case reports in Studies on Hysteria. Anna, Emmy, Lucy, Katharina, and Elizabeth communicated their mental suffering through disabling somatic symptoms like pain, visual impairment, severe breathing difficulties, spasms, and paralysis. For Drs. Breuer and Freud, these ailments of the body became the doorway to the mind. How strange it is, then, that the body has all but disappeared in our psychoanalytic rearview mirror!

If it’s true that “the body keeps the score,” as Bessel van der Kolk wrote in his bestseller of that name, why has American psychoanalysis shown so little interest in psychosomatic phenomena? After all, in this fragmented world the body is one thing we human beings all have in common. This essay is my attempt to offer some thoughts about how we’ve left the body behind and generate some interest in reclaiming it. In what follows I will explore a number of developments within psychoanalysis and in American society that I believe have kept us psychoanalysts from taking a place at a table where we surely belong.

From Chicago to Paris

Freud was a neurologist interested in treating patients who suffered from distressing symptoms of nervous system dysfunction that defied medical understanding back in the late 19th century. One of his earliest insights was that some of these symptoms could be understood as symbols that represented past experiences which could not be allowed into consciousness. This led to a unique way of addressing somatic dysfunction: by providing insight through interpretation. It worked! Psychoanalysis became the first mind-body treatment in Western medicine.

Freud didn’t have much interest in the link between the psyche and the larger corpus of “medical illnesses.” But there were other psychoanalysts like George Groddeck, Sandor Ferenczi, and Felix Deutsch who found this territory compelling. The first systematic psychoanalytic mind-body studies were conducted in the USA where Franz Alexander and Helen Flanders Dunbar founded the Chicago School of Psychosomatic Medicine.

Alexander proposed that every disease was psychosomatic because both psychological and somatic factors take part in its causes and influences its course. He pointed out the intimate connection between acute emotions and their influence on the autonomic nervous system.

While Alexander used the term “psychosomatics” broadly, he believed that there were certain specific physical disorders in which symptoms were the expression of unconscious conflict mediated by a chain of physiologic events that led to pathology. Symbolism was still involved, but indirectly, and in the sense that the affected organ system had a historical connection to earlier developmental mind-body struggles.

A prime example for Alexander and his group were gastrointestinal disorders. The link between mind and the gut had been well established by medical science for hundreds of years and is well known by anyone who has had “butterflies in their stomach” or experienced the effects of increased gut motility that accompanies anxiety. Alexander theorized that the gastrointestinal system was especially suited to express that which could not be expressed in words. Alexander was clear in pointing out that the connections here between unconscious psyche and soma were not directly mediated by symbols. This meant that interpretation of unconscious material was not likely to provide meaningful relief without getting a better handle on the mediating physical factors that were waiting to be discovered.

In 1932, Alexander and his colleagues began a series of studies of patients suffering from chronic organic ailments. They focused on seven specific conditions: bronchial asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, essential hypertension, neurodermatitis, thyrotoxicosis, and duodenal peptic ulcer. The study went on for over 14 years and yielded what the group regarded as confirmation of their hypothesis that these conditions reflected particular psychological constellations.

The Chicago group acknowledged that these patterns were not specific to those individuals suffering from the specific diseases studied and that other factors including the constitutional must be at play. They also were aware of their own potential for bias. In that spirit they recommended follow-up research including clinical material derived from the psychoanalytic treatment of those with one of the diseases they had studied.

As far as I can determine that project never occurred, and the research path of the Chicago group was dropped like a hot potato. Alexander’s work was widely criticized on methodologic grounds, and these criticisms surely must have had an impact on anyone considering picking up where he left off. But in retrospect it seems somewhat unusual that there were no further attempts to develop, expand, or present alternatives to Alexander’s ideas. In any event, this is where the road of psychoanalytic research into psychosomatics ended, back in the mid-20th century.

In the United States.

Actually, it hopped across the Atlantic.

As an illustration of where we could have gone, consider the road that French psychoanalysts set upon in the 1960s and that they have continued to follow until today. The Paris School of Psychosomatics was founded in 1962 by psychoanalysts Pierre Marty, Michel de M’Uzan, Michel Fain, Christian David. The basic idea behind their work was that the body itself was a psychosomatic entity, and that the Freudian concept of the drives was of pivotal importance in understanding the back-and-forth interplay between soma and psyche. For these analysts, optimal health required that “libido” (understood as a “life force”) operate in harmony with the “death instinct.” Under conditions of emotional overload, the two drives become imbalanced, leading to various degrees of physical expression—in some cases, actual death.

As opposed to Alexander, who looked for meaning in specific physical symptoms, the French viewed physical symptoms as the result of a more general reaction to emotional overload. They introduced a particular terminology to express the way in which strong emotions could find mental expression through imagery and fantasy in some but not others (mentalization). They also identified that there were many individuals in whom the capacity for mentalization was lacking, supplanted by “operational thinking” and an inclination toward somatic expression that in some cases became pathological (“essential depression”).

In France today, it remains common for psychoanalytic clinicians to work in concert with medical practitioners to approach somatic illnesses from both directions. That is, analysts try to track the emotional climate changes that accompany the patient’s physical course as followed by their physicians.

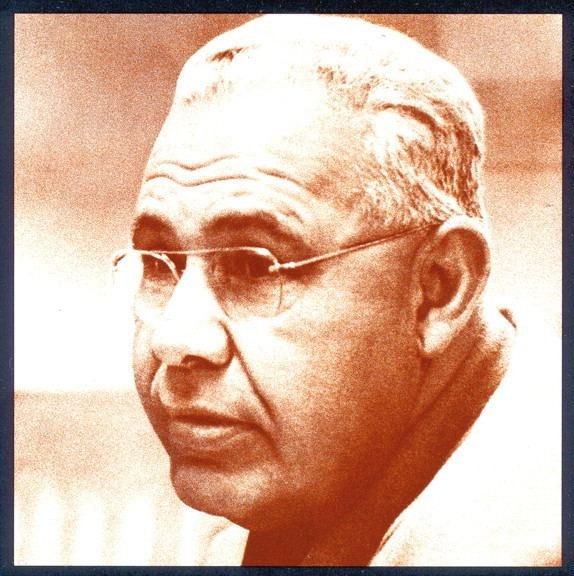

Franz Alexander (1891-1964) was a pioneer of psychosomatic medicine.

Psychosomatics Outside Mainstream Psychoanalysis

How different the situation is in the United States where the divide between mind and body seems to be getting wider and wider. Health care—the province of the body—is an industry that seems to be located on a different planet than the ones we psychoanalysts occupy. This is especially notable since we are living at a time when the connections between mind and body have been worked out to a degree that was only speculative in Alexander’s day. The pathway from emotion (i.e., affect) to inflammatory processes has become more explicit as we have come to understand the role of these processes in so many contemporary ailments.

A brief version of this exciting and unfolding story needs to begin with the work of Candace Pert. Pert was a psychopharmacologist who achieved fame when she identified the “opiate receptor” that could be turned on by small molecules—peptides—that float through our systems and are intimately connected with our emotional states. These “molecules of emotion,” as Pert called them, can act all over the body, at great distances from where they originate. According to Pert’s stress and disease model, emotions can either enhance or suppress the immune system through the synthesis and release of neuropeptides throughout the body.

The manner in which peptides mediate the space between emotions and organ systems is currently being elucidated from numerous corners. Acute and chronic stress, peptides, immune responses, and inflammation have been implicated as links in a pathophysiologic chain common to a host of contemporary diseases.

This emerging awareness of the way in which emotions are related to physical health and illness has led to an increased public appreciation of the importance of psychological well-being to overall health. But the psychological approaches that have followed from this contemporary recognition have come from outside of psychoanalysis. In our contemporary medical framework they reside within a model that for the most part looks at psychological turmoil from the outside in—as something that one “has,” to be controlled and eliminated through the application of some remedy administered by a “treatment provider.” This misses the most important ingredient of the psychoanalytic approach to the mind, which is its emphasis on subjective experience and the unconscious.

Today, in America, the language of subjective experience and its reciprocal relation with the body is spoken for the most part by therapeutic schools outside the psychoanalytic mainstream. For example, the field of transpersonal psychology, which has its roots in the work of Carl Jung, humanistic psychologists like Abraham Maslow, and psychedelic psychoanalysts like Stanislav Grof, has had a close relationship with bodily experience as well as an openness to the language of spiritual experience. Additionally, there has been a surge of interest in trauma-based therapies that focus on bodily regulation as prerequisite to entry into the world of the psyche, especially those informed by the polyvagal theory of Stephen Porges. Up to now, there have been few bridges built between these domains and the mainstream psychoanalytic community, but building these bridges may be a necessary part of taking the body seriously again in psychoanalysis.

Psychosomatics Today: What Happened?

In trying to understand the absence of psychosomatics from the American psychoanalytic scene, I would now like to offer some speculations about a number of factors that may have contributed to its disappearance since the days when Alexander was trying to fill in the dots that connected psyche and soma.

As mentioned above, one of the aims of Alexander’s research was to demonstrate that a connection could be made between specific body pathology and psychopathology. But the nature of this connection may have been too indirect at a that time when, in the public eye, psychoanalytic cure meant “insight through interpretation.” Interpretation had a magical quality to it of the kind that we tend to associate with “miracle drugs” and raised expectations accordingly. It seems likely, from the vantage point of contemporary psychoanalytic experience, that insight and interpretation fell short of fulfilling such expectations when it came to treating physical illness and that, as a result, enthusiasm for the psychological approach in this area might well have gone by the wayside—both for patients and psychoanalytic practitioners.

But the fantasy of cure by interpretation is connected to a historic dilemma in psychoanalysis regarding the role of traumatic events in symptom creation. Very early on, Freud decided that his patients’ reports of childhood sexual abuse were best understood as repressed, wish-driven fantasies. The analytic cure became a matter of interpreting such fantasies, which promised relief for the patient and a degree of narcissistic satisfaction for the interpreter. This general mindset may have interfered with an appreciation of the real impact of the social surround on the psyche, such that psychoanalysts tended to underemphasize the way that traumatic stories can be encoded in physical reactions (as Van der Kolk argues) because they were not encoded as interpretable symbols. Again, the argument would be that just as surgeons like to cut, psychoanalysts like to interpret. That is, analysts tended to downplay possible treatments (and etiologies) that function in a nonsymbolic way. So a combination of public disappointment and professional lack of interest may have converged and impacted on the pursuit of the connection between psychic distress and somatic disease that Alexander and his group was trying to piece together.

Another factor may relate more directly to Alexander himself and his relationship with the psychoanalytic establishment of the time. By the 1960s, Alexander’s thoughts about shortening treatment and his concept of “the corrective emotional experience” had placed him at odds with mainstream psychoanalysis and with his own institute. He moved to California, where he continued his work (including work in somatics). But with his reputation thus tarnished, it seems likely that there was considerable general group pressure to separate from all things Alexander.

From a broader perspective, one cannot overstate the importance of changes in the field of psychiatry and in medicine that were taking place in the United States. During the Alexander years, psychoanalysis and psychiatry were practically inseparable. Most department heads in University psychiatry departments were analysts. This was about to change, dramatically and rapidly.

Unlike in other parts of the world, and counter to Freud’s own attitudes, America had resolved the question of “lay analysis” by trying to restrict practitioners to the medical field. At the same time, the medical field was becoming disillusioned with psychoanalysis as a new generation of medications became available that impacted favorably on many conditions that had been considered the province of psychoanalysis, which did not provide the symptomatic relief that patients and the medical insurance industry desired. The “psychology” of psychiatric conditions became secondary to an appreciation of the constitutional factors (often referred to as chemical imbalances) underlying psychiatric illness. It’s not surprising that there was little room for those interested in studying physical illnesses from a psychoanalytic perspective!

As psychiatrists increasingly moved away from psychoanalysis, the psychoanalytic field was regenerated (one might well argue “saved”) by the entry of nonmedical professionals, assisted by a lawsuit that broke the medical monopoly of the American psychoanalytic establishment. But as psychologists and social workers entered the field, proximity to the body may have waned further in favor of hermeneutic and relational approaches which focused on a psyche that was unlinked to the soma.

Farewell to the Drives?

A central issue here seems to have been the departure from Freudian “drive theory” in the United States and its continued presence abroad. By the end of the 20th century, there was a strong reaction to Freud’s biological orientation as well as a greater appreciation that the universe can’t be objectively understood, independent of our subjective position as participant observers. This means that what happens in psychoanalysis involves the psychological processes of two people, not one. The intricacies of this two-person experience in the here and now took center stage.

But in this atmosphere, the link between psychoanalysis and the body was weakened, if not broken altogether. Debates about the true nature of psychoanalysis began revolving around the question of whether psychoanalysis is a natural science rooted in the material world (Freud’s position from the start) or an interpretive discipline akin to literature and circumscribed by the limits of subjective experience. Prominent analysts like Gill, Hoffman, Laplanche, and Schafer among many others took deep dives into the latter waters.

Perhaps this kind of retreat from the biological offered a potential safe harbor for those trying to protect psychoanalysis from attack by those who challenged its scientific merit (by placing in a category that defied the traditional measurement techniques of natural science). But one of the casualties in this evolution may well have been a full appreciation of the unique importance of the drive concept to psychoanalytic theory.

Freud’s term Trieb (translated as “drive” or “instinct”) is ambiguous: Is it a mental phenomenon or a bodily one? In “Instincts and Their Vicissitudes” (“Triebe und Triebschicksale”), he described it as

a concept on the frontier between the mental and the somatic, as the psychical representative of the stimuli originating from within the organism and reaching the mind, as a measure of the demand made upon the mind for work in consequence of its connection with the body.

The very ambiguity of the term solved the kind of problem we are struggling with today, presuming a mind-body connection as a foundational principle of psychoanalysis. Freud did not let what is called “the hard problem” of consciousness in philosophy (“how does the physical brain give rise to subjective psychological experience?”) interfere with his observations or theorizing about the disturbances in the connection between our minds and the matter of our physical existence.

The concept of drive itself is really a metaphor that provides entry into territory that invites further exploration as an essential part of the psychoanalytic mission. It is no accident that the French psychosomatic school has retained the language of drive theory as they have continued their work on the psychosomatic frontier, while in the United States we have, for the most part, abandoned the language and the pursuit.

One very notable exception is the emergence and growing American interest in “neuropsychoanalysis,” which has acknowledged the importance of the psychosomatic link with regard to current understanding of the brain. Mark Solms clearly articulates the relevance of drive theory to psychoanalysis:

If the mind is part of nature, then it is embodied (what else can it be?); and it is from this simple premise that Freudian drive theory starts. … To abandon drive theory is to abandon this insight, which is the essential connection between psychoanalysis and the body, and, indeed, with the life sciences as a whole.

What Solms expresses so cogently, from the perspective of neuropsychoanalysis, clearly extends beyond the brain to the body as a whole.

Photo by David Baillot | UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering (CC BY-ND 4.0)

Medicalization

In addition to what might be called a “return to dualism” resulting from political and theoretical changes in psychoanalysis and psychiatry, there has been cultural move toward what one of Alexander’s colleagues, Thomas Szasz, had termed (along with others) “medicalization”: a tendency to reify unpleasant bodily experiences and label them as “diseases” that required “treatment.”

This sociocultural vector surely motivated the departure of medically trained and physically oriented psychiatrists from the psychoanalytic field as mentioned above, as it created financial incentives that promoted participation in a system of care that has been intrinsically in conflict with the psychoanalytic worldview.

The effort to meet with the standardization that governs American medical practice led to the DSMs and to an evidence-based approach to medicine that, despites its many benefits, also inflicted some degree of collateral damage as new diseases were added by committee, often in concert with the emergence of drugs tailored to meet these new illnesses.

Perhaps the most relevant example of how this relates to the mind-body interface is the now well-known story of how Purdue Pharmaceuticals medicalized the experience of pain to create a market for a new version of an opiate, OxyContin. In short order, “pain assessments” became part of standard medical practice, paving the way for excessive use of these medicines and contributing to the addiction epidemic we see today.

One of Freud’s most useful concepts was what he called “the secondary gain” of illness. Secondary gain refers to the benefits inherent in the sick role—like being taken care of. As Freud noted, the gratification sometimes obtained from being ill is hard for the individual to give up. By way of analogy, we might then think of a sociocultural secondary gain that benefits the prevailing social and economic order by defining the emotional collateral damage of that order as medically treatable illnesses.

In a sense, this is where Freud began. The emotional collateral damage of his time that expressed itself as “hysteria” had a lot to do with his patients’ reactions to the Victorian status quo. Medicalization is a particularly useful mode of defense for the societal status quo, serving to bury conflicts that arise between individual psychological needs and the social order. There is a clear advantage to those invested in the status quo to medicalize and tip the scale in the direction of the somatic, without regard for the psyche.

But in this “full-circle” moment there is also a great opportunity for us to remember where we came from and to reassert our interest in the frontier between the two.

I would like to thank David Sawyer, MD, for sparking my interest in the topic, and Suzanne Rosenfeld, MD, for her close reading and wonderful suggestions on an earlier version.

Neal Spira, MD, is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in Chicago. He is a faculty member and past dean of the Chicago Psychoanalytic Institute. He currently serves as a director at large on the APsA board of directors.

Published June 2025