Freud as Outsider

New documentary examines Freud’s life and work

By Lucas McGranahanThe train is richly symbolic in Outsider. Freud (2025) by Yair Qedar. All images courtesy of the film.

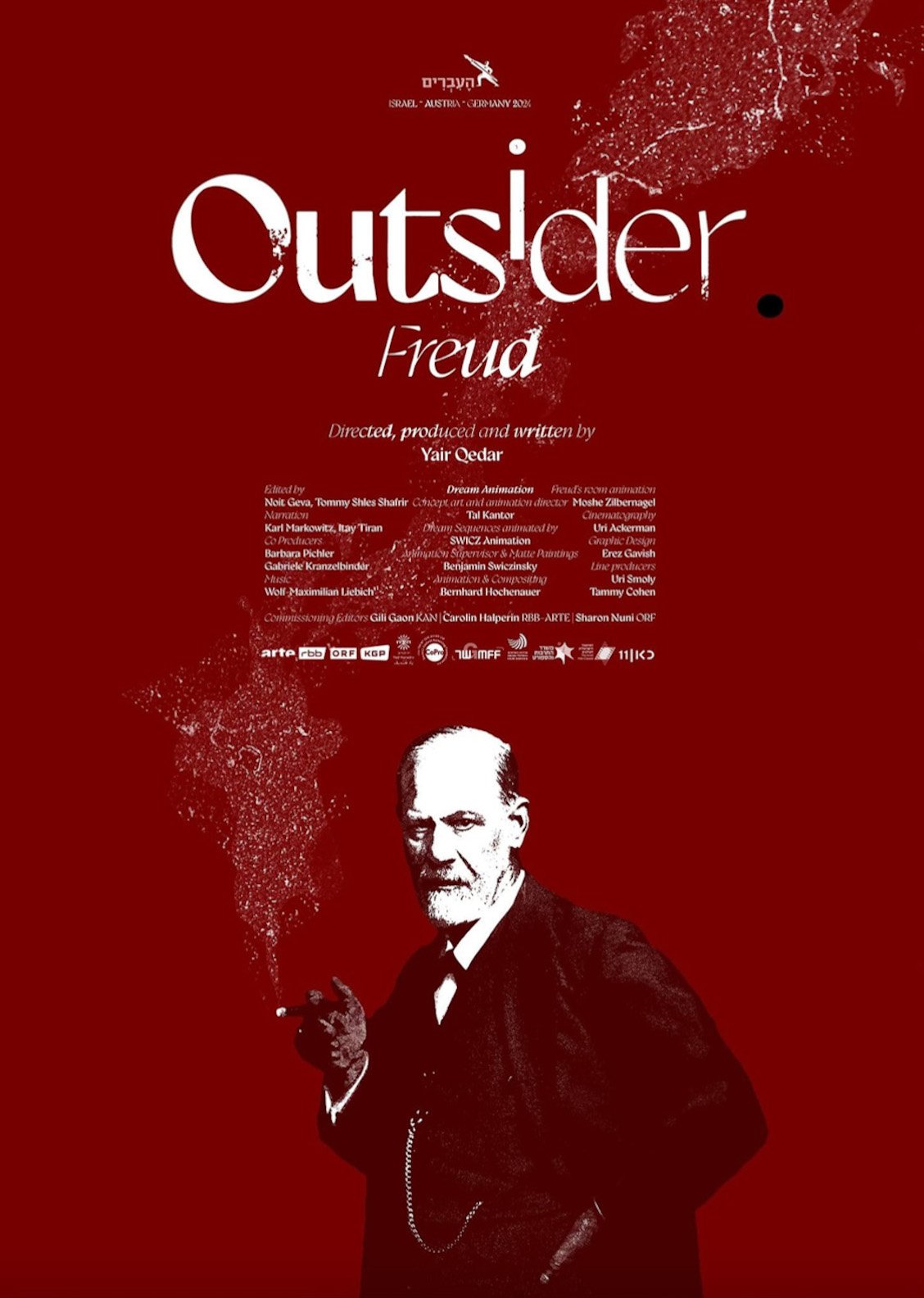

Outsider. Freud (2025), an arthouse documentary written, directed, and produced by Israeli filmmaker Yair Qedar, approaches the father of psychoanalysis through surreal animation, letters, recently available footage, and interviews with scholars and psychoanalysts from around the world. TAP’s Lucas McGranahan spoke with Qedar about the film in May 2025.

The title of the film is Outsider. Freud. How was Freud an outsider?

This is a paradoxical name, or perhaps ironic, because Freud is certainly not an outsider. He is an insider. When we think of ourselves, we think through his concepts. We are all living in this matrix. This is the most written-about person in the modern era. But I found the angle of the outsider, and I found it through one letter.

My journey towards Freud took about five and a half years. I couldn’t find my Freud through his theoretical writing. Not at all. I started to go through biographies. Then I thought, OK, let’s not find the official Freud. Let’s try to find the crack where I can find something new about Freud, and I found it in the letter in the beginning of the film about the train. He goes on the train and someone says, “Close the window, you dirty Jew.” [Freud responds,] “No, I will not close it.” Then the conductor says that in winter all windows must remain closed, so Freud closes it. Later he writes to Martha, “But now I’m OK. I completely got used to it.”

This is a very intense and symbolic moment. How did Freud respond—you know, opposing, but also conforming to authority? And how does he deny the whole incident, saying it’s OK? It is a denial and perhaps it’s a window for us to see his sense of outsiderness. Denial is being outside of yourself.

And then I thought of what Freud had to do with his Judaism—to conceal it, to downplay it in order for the psychoanalytic movement to become universal and successful. Freud belonged to a very marginalized community. Vienna was the most anti-Semitic city in the world. But it didn’t make him feel a victim. He wasn’t dwelling in the sorrow of it. He made it a source of strength, a position that allowed him to see other things.

Speaking of trains, a memorable image in the film is the surreal recurring animation of the train going over the carpet.

The train is a 3D reconstruction, and we tried to make it very central. The train came quite early because I was looking for a master image for the film. The previous one was archaeology. I’m the son of an archaeologist. And Freud has a connection to antiques. This is his main hobby. Also, you know, psychoanalysis is an archaeology of the mind. But I didn’t want to do that. I was looking for something original, like a new filter image that will evoke new things. And then I found many things about Freud and trains. I found them in the Lydia Flem biography. He has many dreams of trains. He has a dog that dies in a train accident. He goes a few hours before every train ride because he’s afraid to wait in the station because he’s afraid to miss the train. Sometimes he splits his family into two trains because of the fear that an accident might happen. The train is a phallic symbol. And for me, as a Jewish person, trains are very symbolic. There are many, many layers in the train, and we try to make it very visual and sensual.

This is part of a bigger film project called The Hebrews. How did that come about?

I didn’t study filmmaking. I studied only Hebrew literature. I’m now 55. Towards the age of 40 I wanted to fulfill my dream to have arthouse films that connect biography and text. How do I tell the life stories of poets and use their poetry and visual language? Each film is different. There is no repetition at all. It’s an anthology, not a series. I produce it all, but I direct only half. I invite directors to direct and embark on a journey that usually takes three, four years each. This film is number 19, and there are now three being made.

Why include a film about Freud?

Israeli television suggested that I expand my project on Jewish writers and poets to Jewish thinkers, and three were chosen: Baruch Spinoza, Karl Marx, and Freud. All their relationships towards Judaism are debatable. Spinoza is critical about Judaism. Karl Marx, of course, is almost a non-Jew. His father converted already, and he writes very juicy things about the Jews and Judaism. And Freud also.

But then, in this long five-and-a-half-year process, I found out why Freud does belong to the project. It’s a very split community, the Jewish community. Many variations of Jewish identity. And Freud represents the secular Jew—no more believing in God, and very critical towards organized religion. So what is left?

He says, “I will always be faithful to this ancient tribe that I belong to, but I don’t know what it means.” And this unknowningness also has a heritage. He’s like a spiritual father for a certain sect of secular Jews who do not know what to do with Judaism and live with this uncertainty, with this vagueness.

What separates this film from other films about Freud?

There are some archives that we’ve not seen in film before. Ninety percent of the home films were shot by [Freud’s patient, colleague, and patron] Princess Marie Bonaparte. The footage was digitized during Covid. We uncovered things like Freud having dinner with his family in Berggasse 19. You see the setting of the table. You see him chewing, playing with dogs, playing with his children. This is footage that was not seen before in other films.

But also the story. Every film invents a narrative of Freud. But my film has two things that are perhaps unique. One is that it’s a combination of arthouse film and a documentary. It’s multigenre, a hybrid. It has interesting rhythms that change all the time. It’s a bit dreamlike. So it’s playful. The second thing is it’s an attempt to put Freud on the sofa and to de-canonize him—because I think he’s suffered from canonization. He became such a Rushmore Mountain of Western civilization. So people project stuff on it, object to it, count his mistakes, the things that he didn’t see, the things that he didn’t foresee, etcetera. So I wanted to detour all of this canonization and try to do a mental exercise to forget everything that I know about Freud and to try to reach him in his time without the judgment of the future. This is what I attempted in the film, and I was doing it through the archive and the letters, mainly.

You have many interviews in the film. How did you find them?

I began with Eran Ronik. Ronik is the main academic adviser of the film, and he has two fields of knowledge. The first one is the establishment of the Palestine Psychological Society [now the Israel Psychoanalytic Society], one of the first in the world. The second one is Freud’s letters. He edits editions of them, so he was my access, and he introduced me to Daniela Finzi from the [Sigmund Freud] Museum. And then I tried to create a list of dominant psychoanalysts and historians of psychoanalysis. It was important to represent countries, cultures, and languages. I didn’t want to Americanize the film, and I didn’t want to Americanize Freud. I think the film has no land.

The main interview, for sure, is Adam Phillips because of the book that he wrote, Becoming Freud. What Adam Phillips did was focus on the first 40 years of Freud, before Freud became Freud. That’s interesting, because Freud resisted biographies. He said nobody can write a biography. It’s not a valid profession. It’s not possible to be true, writing this one narrative. Also he burned his letters at the age of 15 from the fear of future biographers.

Freud is the main witness of his childhood. In his stories, he’s a bit of a hero. And Adam Phillips said that perhaps Freud is hiding from us his helplessness as a Jewish child in the most anti-Semitic city in the world. Where is this helplessness? Perhaps psychoanalysis is the attempt of the grown-up Freud to reclaim power over his helplessness by retelling the story of his childhood, because when you retell the story, you gain control.

How did you decide on the film’s structure of four chapters?

I had bad ideas in the first three years of making the film. And there was a sort of a crisis. And then I began to do psychoanalysis, and quite rapidly through psychoanalysis I understood the structure of the film. I thought of Freud the overcomer—how Freud overcame challenges. So in each one of the chapters he has a challenge that he tries to overcome. The first one is overcoming his Jewish identity. The second one is overcoming the death of his father. The third one is overcoming different deaths that happened to him during the 20s: the daughter, grandson, and mother. And the fourth one is overcoming life—you know, this deal that he had with his family doctor of mercy killing. This is the basic structure, and there’s layers upon it.

You are also an LGBTQ activist. Does this inform the film?

I found the connection from the letter about the train ride: “Close the window, you dirty Jew!” I put myself in Freud’s shoes. What would happen if someone would tell me, “Close the window, dirty faggot!” Could I ever get used to it? And I said no, never! And then I understood something about Freud’s denial. And then I invited the queer psychoanalysts [Esther Hutfless and Fabrice Bourlez] to be part of the film, to draw the connection between marginality and strength—a source of power.

How have audiences received the film?

The ride was amazing, and it is still amazing. I’ve finished 200 screenings already. You know, the film is partly Israeli in the production sense, and we’re boycotted from, I don’t know, half of the world or more. I work with independent cinemas and communities. But I’ve also reached psychotherapy and psychoanalytical organizations. For me it’s amazing because every week I get contacts from another country, another community. There are conferences where people have prepared talks, and after the talks there is a discussion with the audience. I also tried some political screenings, for example, in Nazareth with Arabs and Jews. [We discussed] the question of what it means to be an outsider—how to deal with interculturalism. It’s very moving to see how Freud belongs to us all. He transcends national borders and identities. I’m supposed to come in October to the States to do screenings at the Library of Congress, we’re talking about Cornell and NYU and other institutions. It’s going to be a grassroots process. The conversation becomes connected and bigger.

I want to say that after making the film about Marx, there were many countries and communities that did not want the film because they cannot tolerate Marx. But I made a little research about Freud. I wanted to see whether Freud was canceled. He could have been canceled. And, you know, I checked the discourse around him, and he’s completely not canceled. He’s back. He survived the Freud Wars and he is everywhere—a lighthouse and a pillar for all of us, for how to think of ourselves and what we experience.

To inquire about viewing the film or arranging a screening, contact the filmmaker.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Published June 2025