Psychoanalytic Fiction Writers

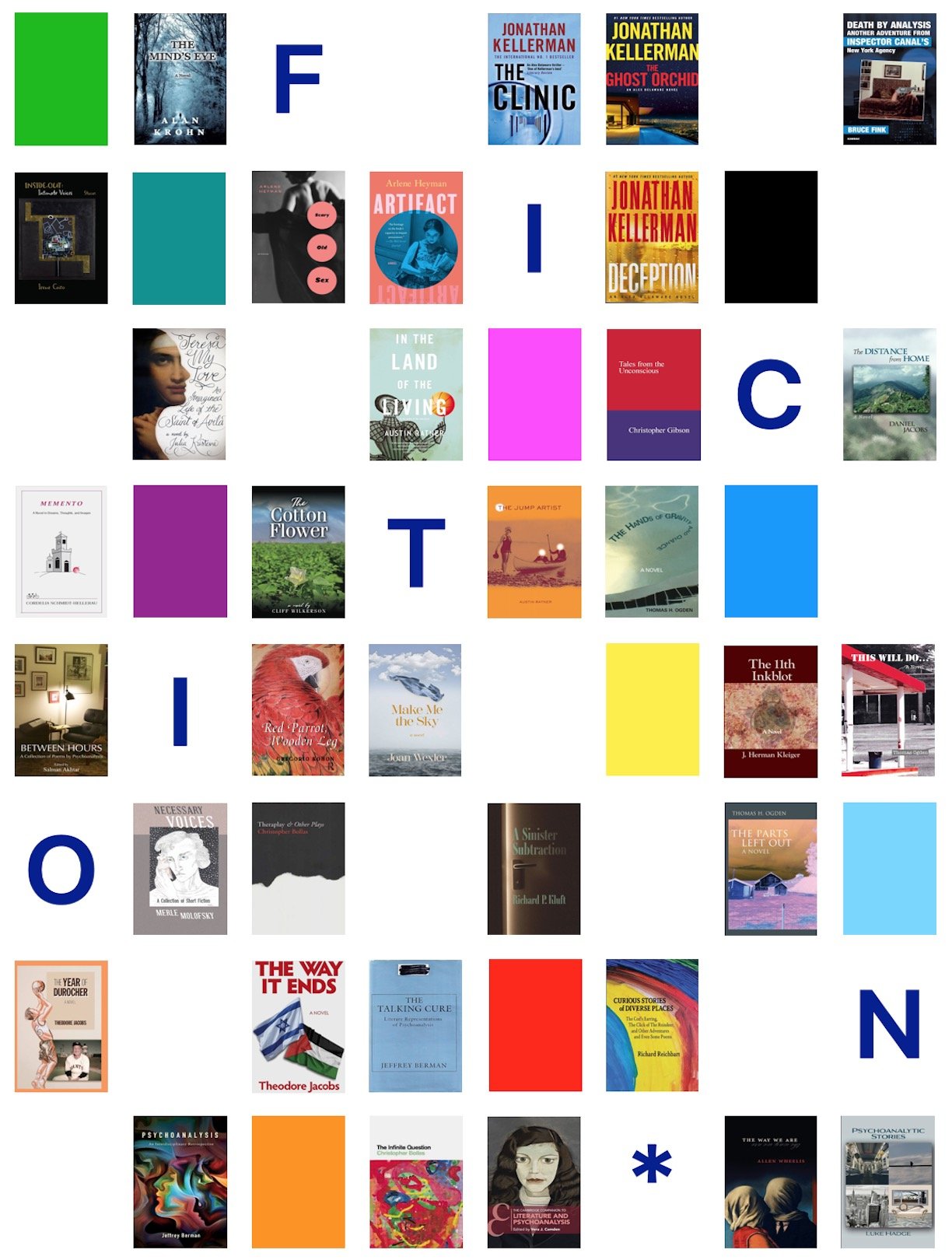

BY JEFFREY BERMANCollage by Austin Hughes.

“In my mind,” Sigmund Freud confided to Wilhelm Stekel as they hiked through the forests of Berchtesgaden, “I always construct novels, using my experiences as a psychoanalyst; my wish is to become a novelist—but not yet; perhaps in the later years of my life.” Freud never became a novelist, but he confesses ruefully in Studies on Hysteria that “it still strikes me myself as strange that the case histories I write should read like short stories and that, as one might say, they lack the serious stamp of science.”

If Freud saw the literary quality of his case studies, he also understood how psychoanalytic concepts could be applied to literature itself. Psychoanalytic literary criticism was conceived when Freud, reflecting on his tempestuous self-analysis, made a connection to two plays, Oedipus Rex and Hamlet, and gave us a radically new approach to reading literature. In the beginning, the marriage was one-sided, with Freud and his followers looking to literature mainly to confirm the truth of psychoanalysis, but now it is more equal. Vera J. Camden, the editor of The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Psychoanalysis, calls it, using a Puritan term, a “companionate” marriage, “not between two minds, but between two mentalities, two languages of human meaning. Literature and psychoanalysis draw from the heart of each other and in doing so foster new creations.”

Storytelling is central to both literature and psychoanalysis, as is language more generally: what is said and not said. Analysts have highlighted the commonalities between writing fiction (or poetry) and psychoanalysis. Salman Akhtar, one of the most prolific contemporary psychoanalysts, has published seven collections of poems. In his edited volume Between Hours: A Collection of Poetry and Psychoanalysis, Akhtar’s observation that poetry and psychoanalysis bring together reality and unreality is no less true of fiction and psychoanalysis. “Both poetry and psychotherapy attempt to transform the unfathomable into accessible, tormenting into pleasurable, hideous into elegant, and private into shared.”

Moreover, reading fiction, and in some cases writing fiction, are required in some psychoanalytic institutes, as Cordelia Schmidt-Hellerau, herself a novelist, points out in Driven to Survive:

When I trained in the 1980s in Switzerland, psychoanalysts were expected to read fiction. Reading fiction engages our imagination; it touches, stirs and works on our unconscious. In similar ways, writing fiction engages fantasy, part of which is always unconscious. Writing fiction strives to reveal, unfold, and free the core of sentences or images that come to the writer’s mind, unbidden, arbitrarily, and on their own. If it’s a sentence, it needs to be unfolded in an image, a scene. If it’s an image, it needs to be elaborated in words. That’s precisely how Freud described the process of making the unconscious conscious. ... Writing fiction is the elaboration of this intimate encounter between what is known and what is implied or hidden, between what is conscious and what is still unconscious.

Given this special relationship of both literature and psychoanalysis to the unconscious, works of fiction by psychoanalytic psychotherapists are of great interest to me. Beginning with my 1985 book The Talking Cure: Literary Representations of Psychoanalysis, I have eagerly read therapists’ fictional and nonfictional writings. Discussions of Allen Wheelis’s many novels and Christopher Bollas’s novellas and plays appear in my book Psychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Retrospective. I discuss therapy stories by the world’s foremost living existential psychiatrist in Writing the Talking Cure: Irvin D. Yalom and the Literature of Psychotherapy.

Storytelling is central to both literature and psychoanalysis, as is language more generally: what is said and not said.

In my present research, I discovered that no one has written a book on psychoanalytic fiction writers, largely because few analysts pen novels and short stories. Gregory D. Graham made a similar observation in 2015. “In a cursory and informal poll of analysts whom I know, I found that these serious readers and educators could not easily recall even ten novels written by trained analysts that had appeared in English in the last few decades.” Graham is right: there are surprisingly few analysts who have written novels—more than ten but probably under one hundred.

In her 1983 memoir Code Name “Mary,” Muriel Gardiner offers an explanation of the scarcity of novels and memoirs written by psychoanalysts: most analysts are “inhibited by feelings of privacy” and by their training. Plausibly, this inhibition, the fear of disclosing too much of the analyst’s private life to patients, much less to the public, has, until recently, stifled psychoanalytic fiction writing.

To help identify the names of psychoanalytic fiction writers of whom I might have been unaware, I sent an email on the APsA listserv in August, 2023. I received over 30 responses. My list of psychoanalytic fiction writers is comprehensive but not exhaustive.

Varieties of Psychoanalytic Fiction

Two psychoanalysts have written historical fiction:

Julia Kristeva’s Teresa, My Love: An Imagined Life of the Saint of Avila spotlights one of the world’s most influential women, a sixteenth-century Carmelite nun whose ecstatic faith and impassioned religious writings continue to inspire countless Christians and non-Christians alike.

J. Herman Kleiger’s The 11th Inkblot illuminates a Swiss psychiatrist whose name everyone has heard of but whose life remains unknown to most people: Hermann Rorschach. Kleiger imagines an encounter between Rorschach and a tormented patient, Anton Zelensky, at times mute and catatonic, shortly after the First World War. The 11th Inkblot is a novel about traumatic loss and recovery, a story as much about time, the art of clockmaking, as it is about the value of verbal therapy.

Detective fiction has a special relationship to psychoanalysis. I was surprised by the popularity of this genre among psychoanalytic fiction writers, nearly all of whom are male analysts. Freud was a fan of Sherlock Holmes, and he realized the close analogies between psychoanalysis and detective work, as the Wolf-Man makes clear in his Memoirs: “I had thought that Freud would have no use for this type of light reading matter, and was surprised to find that this was not at all the case and that Freud had read this author attentively. The fact that circumstantial evidence is useful in psychoanalysis when reconstructing a childhood history may explain Freud’s interest.”

Jonathan Kellerman’s The Clinic investigates the brutal murder of a clinical psychologist, Hope Devane. Abused in early childhood, she restages her trauma, acting it out instead of working through it.

Alan Krohn’s The Mind’s Eye casts light on a different form of trauma, a child who grows up without parents, feeling rage that awakens his analyst’s unresolved anger toward his own mother, who may have committed suicide. Novelists typically portray psychoanalysts who learn about their patients’ lives, but Krohn’s analyst must first unlearn what he has been taught.

Richard P. Kluft’s A Sinister Subtraction contains a patient suffering from multiple personality disorder who accuses her former psychologist of molestation. One can appreciate A Sinister Subtraction without knowing anything about the multiple personality craze that bedeviled psychology near the end of the twentieth century, but the novel takes on greater significance in light of Kluft’s scrupulously fair depiction of the vexed history of memory research.

Death by Analysis, by the Lacanian analyst Bruce Fink, is, arguably, the most sardonic book about psychoanalysis written from an insider’s perspective. Readers will appreciate Fink’s wordplay and his witty account of the ideological warfare between the “Clanians” and “Calanians.”

The Bildungsroman, a type of novel highlighting the growth and education of the writer, like its cousin, the coming-of-age story, holds a special relationship to psychoanalysis. In the following novels, the authors do not call attention to themselves as clinicians.

Gregorio Kohon’s Red Parrot, Wooden Leg dramatizes the perils of reading and writing under a brutal dictatorship. The expressive parrot, Joacaría, is a delightful creature who may remind readers of an even more famous parrot in Marian Milner’s iconic On Not Being Able to Paint, though Milner’s parrot cannot speak Yiddish, as Kohon’s does.

Thomas Ogden is perhaps the best-known contemporary American psychoanalytic fiction writer. The author of three novels, The Parts Left Out, The Hands of Gravity and Chance, and This Will Do ..., Ogden demonstrates the role of childhood experience in shaping character development. Like some but not all psychoanalytic fiction writers, Ogden draws a sharp distinction between his two professional identities. “When I write novels,” he told an interviewer, “I’m a novelist, and when I’m with patients, I’m an analyst.”

Arlene Heyman’s short story collection Scary Old Sex and novel Artifact hint at the central traumatic loss in her life, the early death of her first husband, the psychiatrist/analyst Shepard Kantor. Spousal loss remains the signature theme in Heyman’s writings; paradoxically, the dead not only remain alive in Heyman’s fictional world but also become a muse for her creativity.

Austin Ratner, who is not a therapist but a medical doctor, novelist, and historian of psychoanalysis, has written The Jump Artist and In the Land of the Living, both of which display a different form of trauma, the early death of his father. The Jump Artist and In the Land of the Living are narrated by young men who lose their fathers, the former through an unsolved murder, the latter through cancer. “Father hunger” usually refers to women’s feelings of emptiness for fathers who were absent presences in their lives, but the expression also applies to Ratner’ male narrators, who long for their deceased fathers’ approval.

Father hunger of a different kind appears in Joan Wexler’s memoir A Pot from Shards and novel Make Me the Sky. Wexler lost her father not through death but through his abandonment of his family when she was two, a betrayal that she spent decades trying to understand if not forgive.

Cordelia Schmidt-Hellerau’s Memento shows how fiction writing is both scary and fascinating. The narrator, Sine, yearns to write fiction but, fearing rejection, instead becomes a college teacher of creative writing. Her life is upended when her star student commits suicide.

Cliff Wilkerson’s The Cotton Flower is the story of five people, a mother, her parents, her son living in rural Oklahoma during the Second World War, and a fifth, the father, overseas fighting. Wilkerson initially wrote the novel from the point of view of a nine-year-old boy, but he later revised it to include the viewpoints of the four adults, giving the story a broader focus. One realizes from his two memoirs, Moving On and Still Moving On, that much of what happens in the novel chronicle the many challenges he had to face on the journey from his birthplace on an Oklahoma farm to the office in Chicago where he practiced psychoanalysis.

Theodore Jacobs and Daniel Jacobs are the only two American brothers who are both acclaimed psychoanalysts and novelists. They have strikingly different personalities, prose styles, and literary interests.

Tellingly, Theodore Jacobs’s The Year of Durocher and The Way It Ends, and Daniel Jacobs’s The Distance from Home show how early traumatic experience influences later life. Unsurprisingly, the theme of fraternal twinship appears in both brothers’ writings.

Other psychoanalysts write short fiction. One recalls Julio Cortázar’s pugilistic quip that the novel wins by points, the short story by knockout. Many of the short stories interrogate traumatic loss.

Merle Molofsky’s Necessary Voices contains a story, “Miriam 1960,” about a bungled abortion that almost results in death. The story takes place before the Supreme Court legalized abortion in the 1973 landmark case of Roe v. Wade, but the tale becomes more distressing to read in light of the overturning of Roe in 2022.

Richard Reichbart’s Curious Stories of Diverse Places presents a different trauma, one that every parent fears: the death of a child. The event casts a shadow over several stories in the volume.

The Analyst as Storyteller/El Analista Como Narrador, edited by Cordelia Schmidt-Hellerau, contains stories written by 20 female and 10 male analysts from 17 different countries. The tales reveal intriguing gender differences: the male authors write about the world of ambition, achievement, and individualism, while the female authors write about the attachment bonds of family and friendship.

The most haunting story in Christopher Gibson’s Tales from the Unconscious involves a fellow therapist’s suicide, along with the culture of silence that surrounds the event.

Many of the stories in Irene Cairo’s Inside Out: Intimate Voices emphasize the trauma of early maternal loss, something she was not entirely aware of until I sent her a copy of my chapter.

Luke Hadge’s Psychoanalytic Stories records the young practitioner’s experiences, including treating a world-famous analyst who, not many years earlier, was one of Hadge’s professors.

My greatest surprise in researching this book was the number of analysts who began publishing fiction when they were sexagenarians, septuagenarians, or octogenarians. Thomas Ogden was in his 60s when he began his career as a novelist, as were Alan Krohn and James Herman Kleiger. Others were older: Richard Kluft, Cliff Wilkerson, Richard Reichbart, Theodore Jacobs, and Daniel Jacobs were in their 70s. Joan Wexler and Irene Cairo were octogenarians when their fiction appeared. Who knew that the expression “life begins at 80” applies to so many psychoanalytic fiction writers?

It is not surprising that many of these stories focus on traumatic loss, such as early maternal, paternal, child, or spousal loss. Most people struggle with love and loss, and psychoanalysts are no exception. Often analysts choose to write about traumatic events through the veil of fiction rather than in a professional publication. As Picasso said, art is the lie that reveals the truth. Understanding trauma requires understanding the past, recognizing, as William Faulkner stated, that the “past is never dead. It’s not even past.” As Joan Riviere reports, Freud once exclaimed to her: “Write it, write it, put it down in black and white; that’s the way to deal with it; you get it out of your system”—advice that psychoanalytic fiction writers are finally following.

Jeffrey Berman is distinguished teaching professor at the University at Albany. He is the author of over 20 books, including Psychoanalytic Memoirs (2023), Psychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Retrospective (2024), and Freudians and Schadenfreudians: Loving and Hating Psychoanalysis (2024).

Published June 2024.