Algorithmic Defenses Against Thinking

The rise of UberTherapy

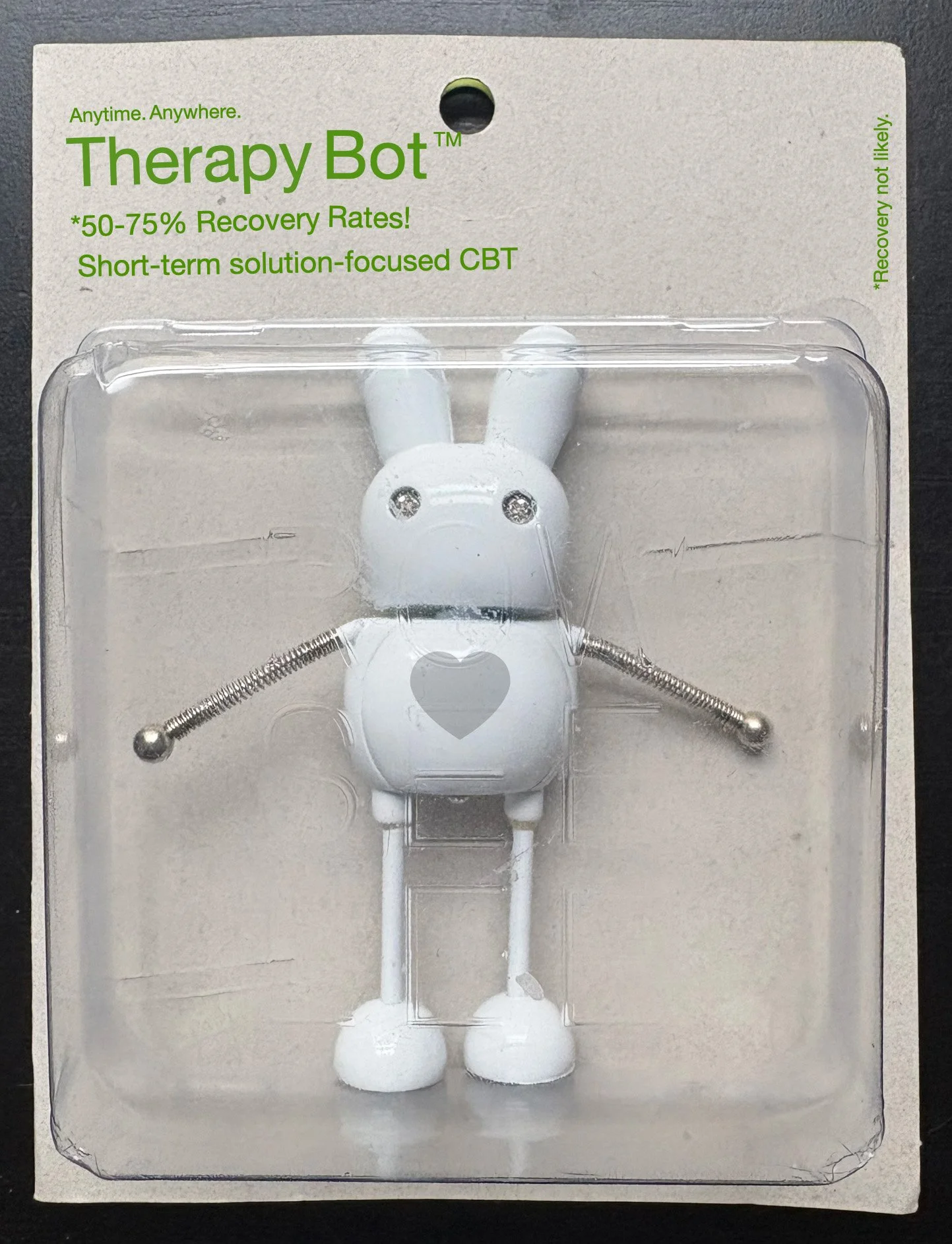

By Elizabeth CottonIllustration by Austin Hughes

I am someone who has skin in the therapy game—a sociologist writing about mental health, a trade unionist, and someone who has been a therapist and has had a lot of therapy. I didn’t know when I started to write my book on the emerging digital therapy business models that so much of it would be about shit and shame. And I didn’t know that the most embarrassing part of therapy isn’t talking about sex, but that many of us are in an abusive relationship with our therapeutic work.

The line of argument of UberTherapy: The New Business of Mental Health is that the therapeutic sector has undergone a process of uberization through the parallel industrial shifts towards marketization (shift from a clinical to a financial logic), standardization and manualization of therapeutic approach, and now the digitalization and introduction of AI technologies into therapeutic labor. Part of this new model involves the introduction of platforms—including online platforms as providers of therapy, practice management platforms in private practice, and AI technologies such as chatbots.

UberTherapy is the term I use to indicate the fluid and dynamic business models of digital therapy that are being utilized as key health care players start to roll out AI across the mental health sector. The book argues that UberTherapy represents an attack on thinking, offering the new consumers of digital therapy a defense against deep work. It contends that inherent in the automation and iconic design of therapeutic labor processes lies a rejection of complexity and a denial of our dependency on others to explore the unconscious. It sets the goal of therapy low, to finding a simple solution to a simple problem determined by an online survey, your e-commercial history, and credit card details. It is in this way that the design premise of online therapy platforms redefines the therapy problem as one of convenience and choice where therapy can be done anytime from anywhere by anyone. With the emergence of short-term, solution-focused, and ultimately “nonrelational therapies,” we are left with a set of transactional decisions about what kind of therapy to buy online.

In the writing of this book I have come to believe that the platformization of therapy offers an intentional unknowing about our psychic realities, a neoliberal framework that does not offer us a stable “framework of care” where we are safe to work out who we really are.

Defenses Against Thinking

One of the proposals explored in this book is the idea that digital therapy offers us a defense against thinking. The argument is that whatever therapeutic tradition or technology we engage in, it has to help us acknowledge and navigate the facts of our lives rather than offering a retreat into what Michael Rustin calls the pathological side-effect of technological systems, which allows us to deny the fundamentally human nature of getting our needs met. And since AI systems cannot, by design, contextualize, think critically, or resolve conflicts, UberTherapy represents a profound deficit in thinking and an unsafe environment for therapeutic work. I argue that this model of therapy offers by design a defense against addressing the conflict—both internal and external—that offers the raw material that many of us bring to therapy.

Using Robert Money-Kyrle’s 1960s papers about a psychoanalytic framing of the political self, I try to formulate the facts of life in relation to the AI-driven world that we are now living in. The proposal is that UberTherapy can be seen as a defense against three intertwined facts of life:

We are dependent on others to grow.

We come into being through a creative act that we are excluded from.

We die.

These facts of life sit uncomfortably with the promise of AI that defends us against our dependencies on others, against our lack of omnipotence or self-sufficiency and the reminder that all things end beyond our control. Despite the seduction of being able to relate via online platforms on demand and ghost people before they leave us, Money-Kyrle’s formulation offers us a psychoanalytic way of assessing the psychic consequences of the shift that is taking place in therapeutic practice as a result of its digitalization and platformization.

In the case of UberTherapy, these deep psychic defenses against thinking are abetted by a lack of industrial thinking. This refusal to think structurally about business is itself a kind of defense. In part this defense is maintained by a lack of clear data and knowledge about the business landscape. Therapy in the UK is being repositioned as a part of the e-commercial sector, a system that measures an inflated sense of its own success and ignores its clinical failures. This is a system where complex cases are signposted out of services and “recovery” is measured in the short term to allow performance data to claim 50–75 percent recovery rates. Importantly in this model, data is not captured to measure the range and number of people who fail to access therapeutic support, allowing the business model to claim commercial success.

The US offers the template for the e-commercialization of therapy in the UK, where this story of uberization involves the movement away from universal access to health care to the rapid introduction of private medical insurance, employee assistance programs, and therapy platforms. As colleagues and I reported in the BBC program “Investigating Employee Assistance Programmes,” the introduction of therapy platforms offers a business model based on attrition by design, introducing the gamification of how we understand and measure therapeutic outputs.

I have come to believe that the platformization of therapy offers an intentional unknowing about our psychic realities.

Back to shit and shame.

In the field of big data there is a phrase that says if you put shit in you get shit out. Bad data are mined and used to develop AI technologies which are based on shaky evidence. Among commentators the idea of “enshittification” describes the trajectory of digital business models: providing subsidized commodities until the point that subscribers and their personal data are pooled, profits are reported, and shares may be sold. This commodification and datafication of therapeutic work survives long enough to extract value and no longer, a business model that is increasingly understood alongside predictions of the bursting of the AI bubble.

Since UberTherapy is a business model where therapists and consumers meet via what Cathy O’Neil calls the shame machines of social media and online apps, the debates about therapy often slip into a popular logic that Bad Therapy = Bad Patient = Bad Therapist. Algorithmic harms are blamed on “bad patients” who think ChatGPT is their therapist and “bad therapists” working within this new platform economy.

As you would expect for a psychoanalytically informed book written by a trade unionist, I do not believe that for the key business players in the platformization of therapy the shaming and blaming of the therapeutic labor process is unconscious. Instead, I argue that it is a deliberate attempt to silence us by disorienting and distracting us from the reality that in these algorithmic systems of work we are all set up for failure. They mis-sell the product, and then we clinicians and patients blame ourselves for its failure to deliver recovery, leaving the shame of the UberTherapy business model firmly within the individuals involved. A cruelty to the next generation of therapists and their customers who over time will have no living memory of what the alternatives once were and are set against each other across the digital barricades.

This dynamic can be understood psychoanalytically as a form of projection. There is an idea in psychotherapy about a toilet therapist that might be helpful in understanding the inevitability of the attack that is taking place on the capacity of therapists to think within this digital context. In psychoanalytic thinking, anxiety and our defenses against it are given central place, particularly our common attempts to split off and project our anxiety externally. In this model, the threat of our aggression killing off something we love, like a decent therapist, triggers a projection of the parts of ourselves we cannot accept—our “shit”—into the “toilet therapist” to rid ourselves of these “shitty” feelings. (I might be pushing the shit motif too far here, but given that we are talking about therapy that acknowledges our infant experiences of love and hate, of the “toilet-breast” and the retreat into blaming mummy for everything, it is not entirely out of context.) In this way, projection does not merely relieve anxiety. It protects the system itself from being thought about.

RealTherapy

I use the term RealTherapy to indicate the future alternative models of digital therapy and as a challenge to therapists to engage with redesigning our industrial futures. If we continue to talk about the micro of online therapeutic process without looking at the economic model behind it, we risk being complicit in a system that increasingly none of us can defend. It is still possible that this model of UberTherapy is not our only future because when the rollercoasters of venture capital crash and burn, we will still be us lugging around our anger and shame and there will still be good therapists wanting to work with that. But the time has passed when we can safely leave the design of the next generation of digital therapy businesses to the socioeconomic project that underpins UberTherapy.

Building our capacity to think and talk about the politics of digital therapy is now part of the process of defending deep work. The challenge for those of us with skin in the therapy game is to confront the blaming of the individual therapist for the failings of a business model and open up a discussion inside and outside of the consulting room about these technologies and the industrial complex behind them. UberTherapy offers an accessible entry point for clinicians to talk to colleagues in supervision groups about the emerging business models of digital therapy. It is an invitation to bring critical inquiry into your trainings and CPD events and ask each other, “What does RealTherapy look like?”

Dr. Elizabeth Cotton is an associate professor of responsible business at the University of Leicester and founder of Surviving Work and the Digital Therapy Project, a group of UK and US researchers studying the future of therapy. Her book UberTherapy: The New Business of Mental Health is published by Bristol University Press.

Published February 2026