The Lasting Power of Father Longing

Frederick Exley’s literary pursuit of Edmund Wilson

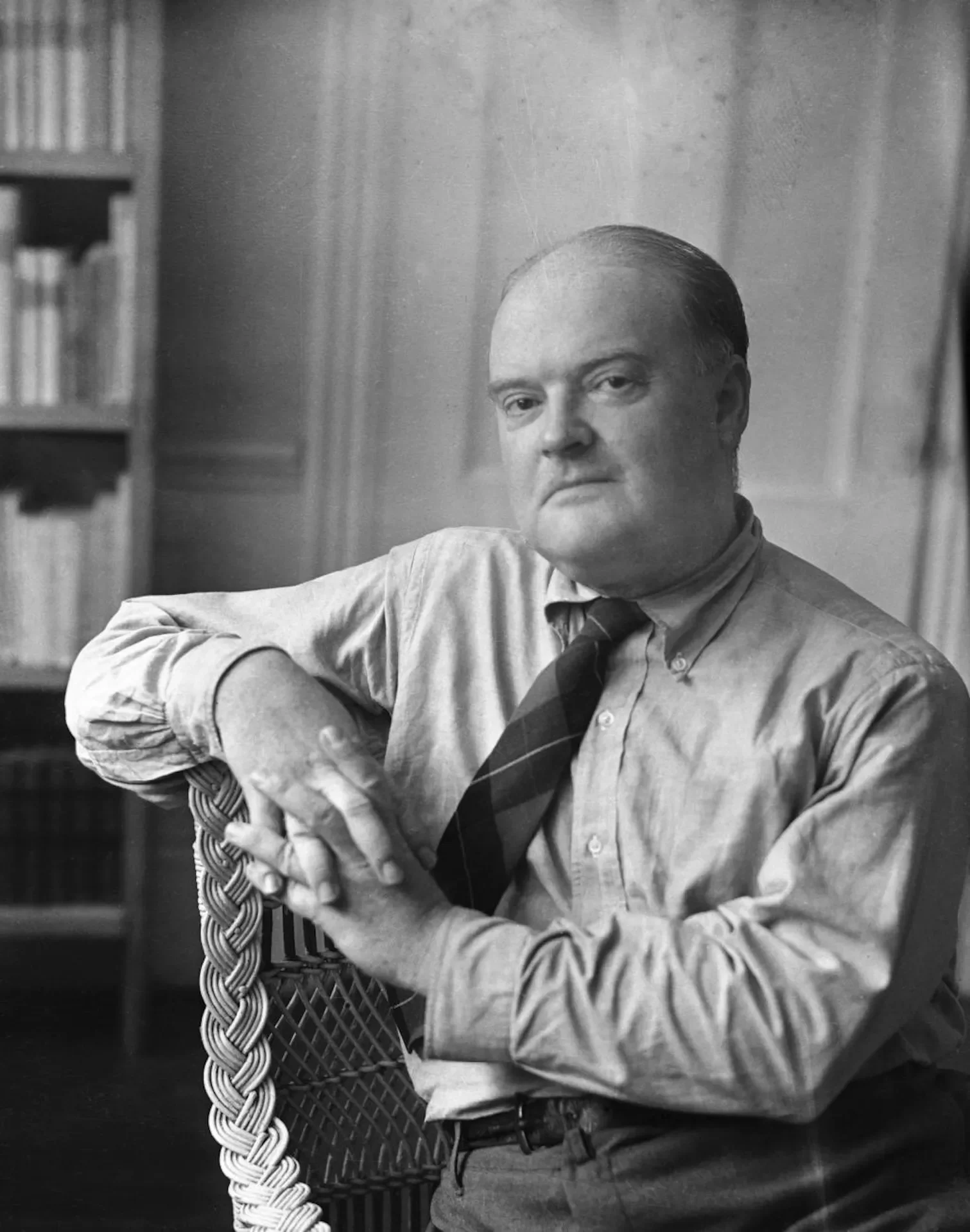

By Michael BrogEdmund Wilson, literary luminary and lifelong obsession of Frederick Exley. Photo by Silvia Salmy (1951).

One of the great unsolved mysteries of American literature is posed by the tortured saga of Frederick Exley. As chronicled in his acclaimed 1968 book A Fan’s Notes, Exley’s life was marked by crippling depression, rampant alcoholism, psychiatric confinements, and a vagabond trail of failed jobs and relationships. His story poses a profound conundrum: How was it possible a man in such spectacular disarray could emerge from the seclusion of his attic with the manuscript for one of his century’s most enthralling and brilliantly crafted memoirs? While I can only shrug at that enigma, there is another question that piques my interest even more: How could a man so gifted descend into such squalor in the first place?

I was considering that very question when I recently opened a carefully packaged copy of Exley’s second book, Pages from a Cold Island. There as advertised, tucked just inside the front cover, was a yellowed, twice folded, unassuming piece of stationery. The dealer had mentioned he had discovered it there and had rightfully charged a handsome premium for its inclusion with the book. But while carefully unfolding it, and then cradling it in my hands, I was still struck by an unexpected sense of profundity: It was a signed letter addressed to my literary obsession Exley, written by his literary idol, the preeminent critic Edmund Wilson.

My wonderment gave way to sadness as I considered how this blunt missive must have landed with Exley. At the time he received it in 1965 Exley was still a completely unknown and unpublished author, an alcoholic teetering on mental breakdown while fighting to find his bearings as a writer. He was a man in dire need of encouragement from an admired hero, but that’s not what he received from the infamous curmudgeon Wilson.

I knew from an earlier reading of Cold Island, a work centered on Exley’s worship of Wilson, that this letter was one of a very few pieces of correspondence between the two men. In 1964 they had exchanged friendly notes in which the fan-weary Wilson, likely impressed by Exley’s literary acumen, had extended the rare favor of a written response. Even more exciting to Exley, Wilson had proposed a future meeting at his summer home in Talcottville, New York, located a mere hour south of Exley’s Watertown residence. Yet when Exley wrote Wilson months later about taking him up on the offer, Wilson brushed him off with the curt note I now held, asserting that his time in Talcottville was reserved “for the purpose of concentrating on some piece of work.” Little did Wilson know that the devoted fan he was so casually rebuffing would soon publish A Fan’s Notes, literature’s most celebrated work about the thrills and discontents of being a fan. Exley would never receive his coveted audience with Wilson, yet seven years later Wilson’s death would evoke in him all the complex reactions one might expect to see in a man who had just lost his father.

Of Fandom and Fathers

Exley first crawled into my brain, where he has since taken up permanent residence, in 2002 when my discovery of his decades old Notes made an almost maddening first impression. Something intoxicating transacted as I paged through his memoir of maladjustment. Like legions of readers before me, I felt pulled into the pages of his story, caring about this lovable ne'er-do-well who wrote as if touched by the divine. With each sentence, I marveled at his astonishing gift for expression—his wit, wisdom, and incisive powers of observation sparkling against the backdrop of his depraved dysfunction.

While A Fan’s Notes highlights Exley’s obsession with professional football player Frank Gifford and the New York Giants, the fan motif carries other important meanings in the book. At a deeper level, it’s a reference to most sons’ first object of avid fandom, their father. In Notes Exley radiates both reverence and resentment towards his father Earl, a semipro football legend in football-mad Watertown, New York. Exley idolized his celebrity father, but the close bond of affection he so desperately craved from him never materialized. He learned that the adoring crowd’s claim on his father’s attention was something with which he could never compete. He ruefully recalled the Saturday morning walks with his father through town, his father captivated by the throng of admirers with which “he assured himself of his continuing fable.” When a line of cheering children chased after them on the street, his father readily proclaimed that they were “all my boys,” oblivious that his red-faced son had come to feel “indistinguishable from all the rest.” His father’s obsession with glory lead Exley to reflect, “Other men might inherit from their fathers a head for figures, a gold pocket watch all encrusted with the oxidized green of age, or an eternally astonished expression; from mine I acquired this need to have my name whispered in reverential tones.”

In one notable scene, Earl competes against Fred at a school function, the parents-vs.-students basketball game. During the proceedings Earl is unable to restrain himself from publicly showing up his humiliated son, who soon woundedly retreats home thinking “Oh Jesus Pop! Why? Why? Why?” As young Fred’s anger rose, he began to secretly long for his father’s destruction. Tragically, before he had a chance to work out his rage, his terrible wish came true when he witnessed his father consumed by lung cancer. Fred was only 16 and already beset with the melancholy he would carry for the rest of his life.

Psychoanalysts might here debate the psychological mechanisms that best explain Exley’s ensuing functional collapse. Was he paralyzed by unresolved grief for his father? Did guilt over his rage leave him hellbent on self-destruction? Was he undermined by the shame of being unable to measure up to his father’s successes? Or did the source of the trouble lie deeper? Had the thwarted connection with his father left something important unformed at the heart of his personhood? Heinz Kohut emphasized the crucial role played by an affirming relationship with an admired father in a son’s development of standards for living, self-esteem, and resilience. A derailed paternal relationship may result in depleted ambition, consumptive emptiness, and a lasting hunger for fatherly recognition.

But the need for connection with a loving father may persist beyond even the death of a father. Sometimes a new hallowed figure may appear to revive strivings for connection that had earlier been frustrated.

Edmund Wilson’s home in Talcottville, New York, to which he invited an ambitious young Frederick Exley. Being disinvited was a massive psychic blow for Exley. Creative Commons license.

The Search for a Substitute

Love of football aside, it gradually emerges in Notes that Exley’s true passion was his quiet devotion to literature. His Frank Giffordses in literature included Bellow, Nabokov, Hemingway, and, as already noted, the luminary critic Edmund Wilson. Wilson was Exley’s first “literary romance,” and his essays served as Exley’s treasured guide to the literary world. In Cold Island, we learn more of Exley’s immense reverence for Wilson, a man residing just an hour down the road in Talcottville but remaining tantalizingly out of reach while occupied with “some piece of work.” (Wilson’s phrasing would ring grievously in Exley’s ears for years to come. In a 1974 Atlantic article on Wilson, Exley referred to Wilson’s habitual absorption in a “piece of work” three times, an apparent wry joke to himself that is left inscrutable to the reader.) I imagine Wilson’s dismissal note to Exley hitting him as a painful reminder of his father’s inattention, but it was not absorbed without protest.

Exley writes in Cold Island that upon receiving that stinging send-off, and then “swilling a six-pack for courage,” he indignantly phoned the renowned man of letters to remind him of his previous invitation. Wilson refused to acknowledge it and demanded Exley explain who he was to be making claims on his time. The deflated Exley replied he was “nobody” and apologized for the bother. He recounts, “before ringing off, the great man, in his cooing pitch, spoke his last words to me: ‘Stout fellow!’”

Three years later A Fan’s Notes won the William Faulkner Award for Notable First Novel, was a finalist for the National Book Award, and was proclaimed by Newsday to be “the best novel written in the English language since The Great Gatsby.” Exley, no longer a “nobody,” pined again for the opportunity to connect with Wilson, likely craving the chance to say, as if to his own distracted father, “look at me now!” Significantly, in the weeks just before Notes was released (and again in the weeks after its release), he travelled to Wellfleet, Massachusetts, and rented a cabin near Wilson’s Cape Cod home. For a time, he basked in the glow of Wilson’s proximity, scheming scenarios for a chance encounter while contemplating the fortunes of his new book. He topped his correspondence from this period with the same heading used by Wilson (“Wellfleet, Cape Cod, Massachusetts”) as if nurturing a sense of deep kinship. But his longed-for meeting with Wilson never came, the possibility finally extinguished by Wilson’s death in 1972.

Exley’s reaction to the reports of Wilson’s demise was severe. He described experiencing “a mania of Wilson lurking all about me,” “seeing Wilson everywhere,” and hallucinating Wilson speaking to him before finally succumbing to “the worst crying jag I’d ever had.” A line from Nabokov’s Pnin echoed mournfully in his head: “I haf nofing left, nofing, nofing.” While sensing these responses emanated from a buried “lodestone of grief” (for his father one might think), he rejected the “Freudian voodoo” of attributing unconscious meanings to this surprising outpouring.

His next maneuvers, however, could have sprung straight from a Freud case study in Oedipal enactments. With his deluge of grief played out and Wilson freshly interred, Exley wasted no time in arranging to meet Wilson’s daughter Rosiland and beloved assistant Mary, whom he plied for secrets of the dead father. Rather than suffer the torments of the rejected son, he assuaged his grief through becoming the manly seducer of Wilson’s female associates, with his attempt at romantic picnicking (at Wilson’s own former picnicking spot) culminating in comical failure.

With these passages, Pages from a Cold Island adds essential context to Exley’s story. One discerns he is still, through Wilson, attempting to work out unresolved grief and longings in relation to his father. But in choosing an inaccessible figure with which to reenact these struggles, he was sadly setting himself up to repeat, rather than transcend, the disappointments of his past.

The need for connection with a loving father may persist beyond even the death of a father. Sometimes a new hallowed figure may appear to revive strivings for connection that had earlier been frustrated.

The Drifter’s Life

The resounding acclaim A Fan’s Notes received did not reset Exley’s life on a new trajectory. After producing that singular masterpiece, he would never again publish anything of comparable literary significance. Locked in a carousing persona reinforced by his own literary descriptions of himself, he would live out his remaining 24 years as the same “simpering, stuttering, drunken and mute mess” he so memorably described in his 1968 Notes. His continuing displays of merry imbibing barely concealed his persisting inner anguish. His revolt against the shackles of gainful employment required that he live off the largess of indulgent friends and family, while his perpetual drifting ensured that nobody ever got too close. His two marriages were brief and inconsequential, and he was largely absent from the lives of his two daughters. His compulsive philandering proved unsatisfying. “I remember thinking” he once said of his partner-hopping, “this is supposed to be fucking freedom. This is fucking damnation baby.”

He pursued recognition from more celebrated writers of his day, the likes of Styron, Cheever, Gaddis, Vonnegut, and his future biographer Yardley. This outreach typically arrived in the form of late-night alcohol-infused telephone calls, one-way conversations that left no room for meaningful exchange with their often-exasperated literati recipients. Some gleaned that beneath these frantic attempts at connection lurked a man who was “irredeemably solitary.” Yardley concluded that Exley lived “utterly, irrevocably on his own” and that “his loneliness must have been unbearable.”

Though Exley bears full responsibility for his self-imposed hardships, the bitterness rooted in his relationship with his father played an undeniable role in shaping his path. It is notable that, while taking pride in his father’s accomplishments, he lived a life diametrically opposed to Earl’s blue collar, hardworking, family man example. In Exley’s evasion of responsibility, we can see a hardheaded rebellion against a father who was a source of repeated disappointment. In his emotional distance, we can detect a repudiation of childhood needs for affirming affection and direction, needs that appeared to briefly reemerge in hopes that another idealized figure, Edmund Wilson, might discern his true gifts, perhaps even champion his cause the way Wilson had once championed Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Auden, and Nabokov.

What if Wilson had stayed true to his initial offer? What if he had gratified young Exley’s bid for a meeting, recognized his genius, offered support, struck up a mentorship, and sobered him up with stern guidance? It’s easy to see Exley hoping for a sequence such as this. Perhaps he intuited the ferociously productive Wilson was someone he could finally allow to model the discipline he needed to remain anchored in stability. Might a more generous responsiveness from Wilson offered at that crucial time have helped fill the void left by his father and eased the emptiness that gnawed at his soul?

Impossible to say. As it played out, Exley’s post-Notes life crashed into the reality that it takes more than artistic achievement to resolve inner anguish. Sometimes it’s only through having one’s core attributes affirmed by a sufficiently admired figure that the scaffolding can be laid for steadied, resilient personhood. Sometimes guidance can only be accepted if it comes from someone reverentially respected. Sometimes, for a son craving the love of an idealized father, it’s only through absorbing the affection of a venerated figure that impediments to growth can be overcome. Sadly, apart from his efforts at connecting with the adulated Wilson, Exley appeared to have closed himself off from accepting much-needed guidance from others who generously had it to offer.

Exley’s father longings, however, did not completely die out with Wilson. In the third book of his trilogy, Last Notes from Home, we meet the formidable James Seamus Finbarr O’Twoomey, a larger-than-life Irishman who befriends Exley in his Hawaiian travels. O’Twoomey proves an intimidating presence for Exley, a powerful man of influence who can more than match his talents for drinking and verbal jousting. O’Twoomey’s arc takes a sinister turn on the island of Lanai where he abruptly holds Exley hostage. Exley eventually discovers that his imprisonment is an act of love, an attempt to enforce sobriety and structure for the purpose of helping him complete his long-stymied final manuscript. O’Twoomey’s appearance speaks to Exley’s continued yearning for a strong authority figure who can appreciate his talents and instill discipline in his life. But the fact that O’Twoomey is, unlike most everyone else who appears in his trilogy, an entirely made-up character, suggests Exley had by this time given up on finding such a person in reality.

Exley’s journey was, as William Gass said of A Fan’s Notes, “a powerful and bruising experience.” In traversing life’s grid-iron, he absorbed more hits than his hero Gifford ever endured as a Giant. He not only faced down adversity, he did his best to create it. But at least, he might have told himself, he lived strictly according to his own rules, “stoutly” guarded against anyone (after Wilson) becoming so important that he couldn’t weather their loss. When he wore out his welcome, as he often did, he could always move on to the next friend’s couch, the next sympathetic woman’s arms, the next boozy phone call, the next awestruck admirer to sidle up to him at the bar.

Michael Brog, MD, is a psychoanalyst in private practice in St. Louis, Missouri, and vice president of the St. Louis Psychoanalytic Institute. He has previously published in Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association on the work of Harry Guntrip.

Published February 2026