Fashion’s Deep Surface

Valerie Steele on Freud, fetishism, and the emotional life of clothing

By Austin RatnerWill it open or is it safely pinned? This dress by Gianni Versace is included in Dress, Dreams, and Desire: Fashion and Psychoanalysis, an exhibition curated by Valerie Steele. Photo by Tati Nguyen.

What if the clothes we wear are not merely decorative but a second skin alive with desire, defense, and fantasy? This is the question animating Valerie Steele’s latest exhibition, Dress, Dreams, and Desire: Fashion and Psychoanalysis, on view at the Museum at FIT in New York City until January 4, 2026. Steele, a cultural historian and the museum’s longtime director and chief curator, has spent her career illuminating the meanings that cling to garments, from the corset to Gothic glamour. Her new book expands the exhibition into a sweeping account of how fashion and the psyche have always been entangled.

In December Steele spoke with TAP’s Austin Ratner about Freud, Lacan, and bringing the language of psychoanalysis to bear on dresses, silhouettes, and stilettos.

The exhibit is really fantastic. You’ve made it so accessible and so inviting. Let’s start with your idea that fashion is concerned with the “deep surface.” What do you mean by that?

When I started studying fashion in graduate school—when I had my epiphany that it was part of culture and I could be a fashion historian—I was struck by how people thought that fashion was superficial, especially in academia. It was material, not intellectual. The life of the body, not the mind. But it really has to do with your feelings and your sense of identity.

Freud also thought in terms of an archaeology down into your unconscious, and the unconscious fears and emotions would display themselves on the surface of your body, like a psychosomatic rash or blush. What you’re feeling inside, that emotion suddenly is exposed, and you might not want to expose it in front of other people.

I was worried that my audience, mostly a fashion audience, would think, I don’t know anything about Freud. Or Who reads Freud anymore? as one young person said to me. So I wanted to emphasize that you know more than you think you do. And we can walk together through this. You can see the effect that [psychoanalysis] had in the first room, the effect it’s had on culture. And then in the second room, taking key ideas from psychoanalysis and exploring them.

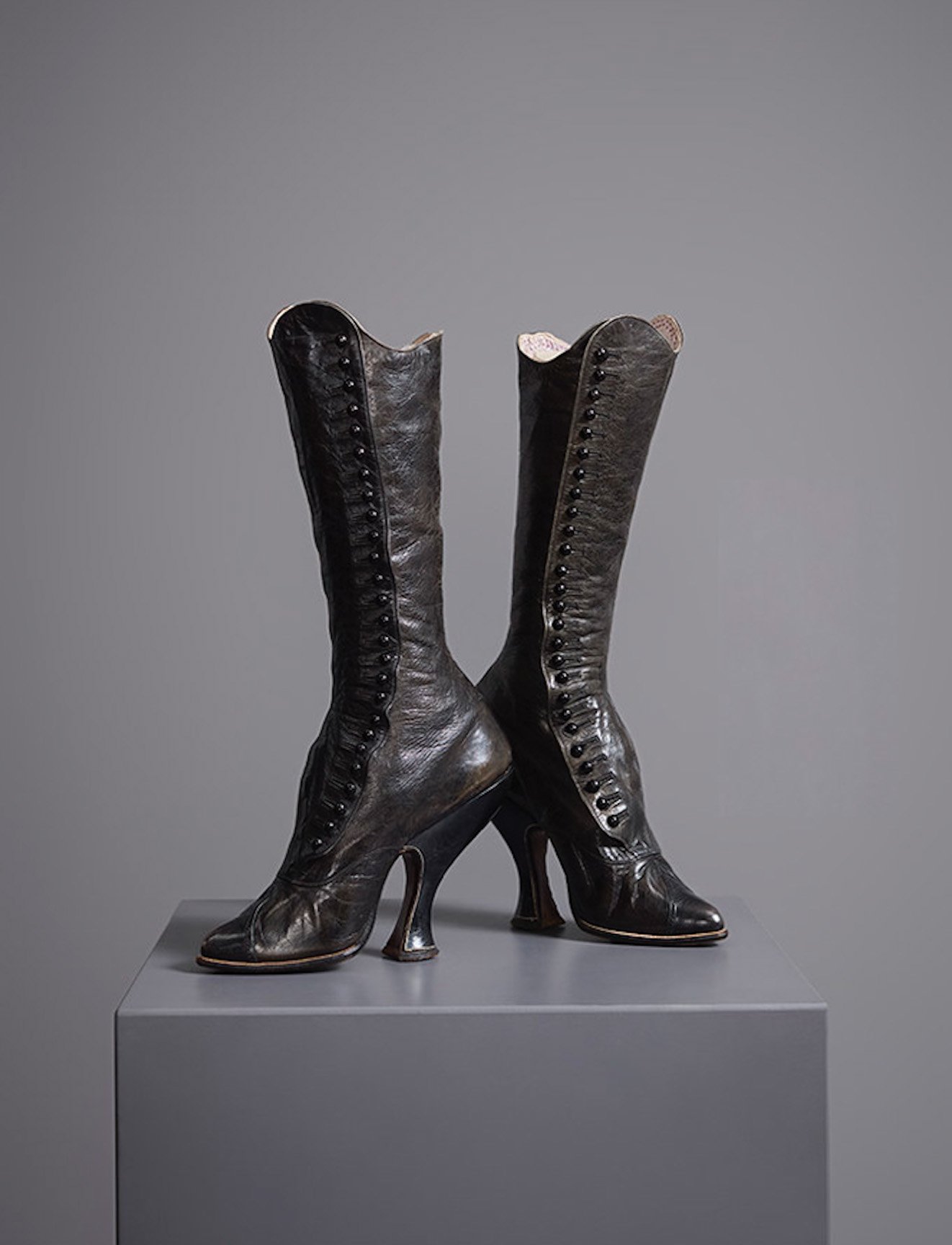

Pair of fetish boots, European, c. 1895. Francesca Galloway, London. Image © Francesca Galloway. Photo by Katrina Lawson Johnston.

How did you first become interested in psychoanalysis?

I read Interpretation of Dreams when I was a teenager and immediately found phallic symbols everywhere. I remember my mother saying, “Oh, you’re just like your father, stubborn as a mule and obsessed with sex.” And then Peter Gay was a professor of mine at Yale. I was aware that Peter was a practicing analyst and that he really adored Freud. There were other people in my class who said, “I don’t believe in penis envy.” And he said, “You don’t need to,” which I thought was great because you don’t have to swallow anybody’s theory whole.

So I went in from that point of view, and it was exciting for me to discover that Freud actually was very interested in his own fashion, his own self-fashioning. Those letters to his fiancée are so revealing, and yet he mentions fashion so seldom in his published work. It’s almost as though it’s this repressed element that he doesn’t want to talk about.

My doctoral dissertation was about the erotic aspects of Victorian fashion. I read Freud along with other people. There were some ideas like the libido for looking and the attraction of concealment that played a role in any interpretation of eroticism and fashion. It was only much later, in 2012, when Suzy Menkes, the fashion journalist, wrote an article about me titled “The Freud of Fashion.” She had seen a bunch of my shows. She’d seen The Corset: Fashioning the Body and Gothic: Dark Glamour and Love and War: The Weaponized Woman. And she thought I was very Freudian and that I looked beyond superficial things like trends into what fashion might mean. So I thought that was flattering but nervous-making because at that point, in the US especially, people were not into Freud. It was a low point in the culture wars against Freud.

A couple of years later, I was invited to give a talk at the London College of Fashion organized with the Freud Museum. So I talked a little bit about Freud and I met some psychoanalysts who were also really interested in Lacan. And so I thought, Gee, do I have to read this guy? And that, of course, took a while. Gradually this idea came that I could do an exhibition on it. But I wanted to see if I could actually write a whole book on it myself rather than just editing a book with chapters by real experts. And so that took like five-and-a-half years. I sort of pieced together the things that Freud had said and things that Lacan and Anzieu had said and others and found a way to approach the cultural history of fashion and psychoanalysis.

I don’t know Lacan very well.

Hardly anybody in the US does. Lacan’s idea of the mirror stage fit in so well with the idea of your body image, the body in your mind. At one point I called a psychoanalyst, Anouchka Grose, and I’m like, “How can I get through this Lacan stuff? This is like fighting your way through a jungle with a butter knife instead of a machete.” And she’s like, “The mirror stage is the easiest one to understand first.”

It seemed to work so perfectly with Schiaparelli because her mother called her ugly and she didn’t recognize herself in mirrors and talks about mirrors a lot in her memoir. But she makes these beautiful clothes, which I think are intended to beautify the woman and beautify life. I really wanted to emphasize the mirror stage with that huge mirror that I put in the entrance to the second gallery, by confronting visitors: This is about you and your mirror image. In the back room, I wanted them to sort of plunge into their unconscious and into the night world of dreams.

I think I read on one of your placards that the first iteration of the mirror stage, according to Lacan, is the mother’s gaze.

He implies that, but the one who actually says it is Winnicott. I had this argument with my husband, because I was explaining about Lacan: The little man’s mother holds him up and he looks in the mirror and, you know, he can’t walk, but she’s holding him up and smiling. And he sees his ego ideal in the mirror and says, “That’s me.” And Lacan goes, “It’s not you. You’re just this little handicapped person who can’t even stand up.” And my husband said, “But not all children look in mirrors.” And I said, “No, the point is it’s the mother’s gaze.” And later, when you’re a teenager, your peers’ gazes. You’re internalizing all the ways these people look at you.

Mirrors greet visitors of Dress, Dreams, and Desire: Fashion and Psychoanalysis. Photo by Tati Nguyen.

You have more than just dresses and suits and things in the exhibit. You have really cool inkblot art, based on the Rorschach test. You have these incredible psychoanalysis comic books.

I found those online. I was ecstatic.

You have Jennifer Lopez’s dress from the 2000 Grammys that was designed by Versace and was such a sensation at the time that supposedly it inspired Google to engineer the Google image search.

Well, apparently it broke the internet. Everyone expected that it would fall apart, but it was constructed very carefully. That dress really had the allure of a striptease, like people were waiting for the malfunction. And I was reading psychoanalysts saying this is what fashion’s about: Now you see it, now you don’t. You saw it also with the safety pin dress that Gianni Versace did. He said, “That’s why it’s called a safety pin, because it won’t come open.” But the point is people anticipated that it would.

That Now you see it, now you don’t is also what’s behind fetishism. And that, I think, could imply that maybe for women as well as men, a key aspect of desiring things, the object of desire, has to do with fetishizing. Traditionally, we’ve always said that men are the ones who fetishize, and women, well, maybe they self-fetishize their body, but it’s usually to attract men. Although I couldn’t figure out quite what female fetishism would be back when I worked on my book Fetish, Fashion, Sex, and Power, this seemed to be a step in the right direction. It’s clearly not the same. Women are not desperately looking for phallic symbols the way men seem to be, but they are getting the same kind of pleasure from some of that mysterious allure that you can get from thinking you’re seeing something but not being sure.

When you see a fashion exhibit it seems so clear that fetishes as a big part of fashion. It’s almost like evidence that brings you back around to take seriously Freud’s theories of fetishes and how they might relate to castration anxiety and other kinds of anxieties.

I remember I gave a talk once to a group of engineers and cell phone designers about sexual symbolism and clothing. So, high heels and corsets and top hats and stuff. And afterwards, this engineer came up to me looking very suspicious and grumpy. And he said, we have this kind of cell phone we call a candy bar. We have another kind we call a clamshell. He said, “From what you said, I gather you think there’s something sexual about that.” And I’m like, candy bar, clamshell? No shit, Sherlock. I would say there’s something sexual about that. I couldn’t believe he was so naive.

And then we had the candy bar dress in the show, which was wonderful. The Hershey’s chocolate bar dress, which, yes, it’s phallic, but it’s also about oral pleasures and turning the woman into something who’s good enough to eat. I mean, the whole thing is completely sexual and wish fulfillment.

In a way, it doesn’t surprise me that Freudian ideas about sexuality might be less offensive to a fashion designer than they might be to others out there.

Because it’s about your body, which for all that it’s fragile and vulnerable is also sexual and has all kinds of pleasure centers in it.

Although, of course, from the 30s to the 70s, whenever fashion people or fashion writers would try and use Freudian ideas to analyze fashion, it was usually so crude and pathetic that I think it turned a lot of people off. I mean, I remember Alison Lurie, who said, you know, “An umbrella is a phallic symbol, which explains why a small or broken umbrella is so embarrassing.” I wrote in my first book that this is really oversimplified. And she wrote me this angry letter and said, “How dare you accuse me of oversimplifying this?” And I wrote back and gave her a couple more examples. And she wrote back, like, “Don’t you ever write to me again.” And I thought, You’re the one who wrote to me, lady!

That’s a great story.

But yeah, it was very oversimplified and usually had to do this very primitive idea of female sexuality. So I think that made it problematic to even think about Freud. You had to do it in homeopathic doses. Like, I think the corset is something which you have to use psychoanalysis to think about in terms of what’s going on with this sort of hard, erect, and yet curvy, weaponized woman. But it’s more than that. It obviously exists within the context of a society and women’s lives and choices.

Jeremy Scott for Moschino, evening gown, fall 2014, Italy. Photo by Eileen Costa.

The exhibit does a lovely job exploring tensions of opposites that are entwined in fashion. The desire towards the naked body and at the same time covering it up, disguising it.

Even in my first book, I said how people testified to the attraction of concealment, that it would arouse curiosity and the desire to go beyond the covering, to unveil it. And yet, there can be something scary about the body, too. Only as I’ve gotten older have I thought more in terms of the body as being something that’s very fragile and something that ages and gets broken and that you would want to hide from other people. I always tended to dismiss this protective aspect. It became more and more clear that people would want something like that. Even on a nude beach, you train yourself not to look in certain ways at people. Nakedness is vulnerable. It also can be scary or disgusting.

You have one section entitled Ugly Feelings. It’s kind of a meditation on the way fashion can hide and contain certain feelings, but also express them.

The classic case is envy. It’s a really ugly and embarrassing feeling, but we all feel it at times. And some people deal with it by projecting it onto other people: I don’t envy you—you envy me. And other people will try and say, “Oh, no, there’s nothing to envy here,” you know, as if you had fear of the evil eye. Because if someone envies you, that’s dangerous because they would like to take you down a peg. Whereas other people will be like, “I’m so fabulous and wonderful. You’re the one who’s envying that I’m wearing this incredibly expensive thing and I have the figure to wear it and the money to buy it,” et cetera. Even though we don’t talk much about penis envy, people do still tend to think of envy as being a female emotion, that women will be competing, they’ll be envious of each other.

I loved that big, coat dress with the spikes coming out of it by Viktor & Rolf that’s in the Ugly Feelings section. During COVID they couldn’t do a fashion show, so they just did a video and you watched it online. And when that coat dress model came out, the voiceover said, “You’re angry. You have a right to be angry.” Well, yes, people were angry about COVID, but there were also ambulances going by and there were freezer trucks with bodies in them. Anger can feel righteous, like I’m mad as hell, I’m not going to take it anymore. And that’s much more comfortable than feeling scared or feeling really sad. So you might use anger to pump yourself up and to hide or push down those other emotions.

And wearing a second skin that has spikes on it is a lovely visual representation of what you just said, the use of anger to cover over vulnerability underneath.

Absolutely.

In a different section, another dress that was incredibly beautiful has a huge skirt with razor blades on it.

Yes, Jun Takahashi of Undercover. He’s so brilliant. He’s always played with what he calls cute and scary imagery. The first time I met him, I was going to interview him. So I bought a blouse of his, which had what looked like little purple flowers on it. When I wore this blouse, people would smile and they’d look closer and they’d jump back because what looked like flowers were actually vampire lips with teeth. It seemed so perfect: the roses like love and life, and then the razor blades like the death drive and destruction and despair.

I found out about Sabina Spielrein and her whole idea, not just that making love involved both the Eros and Thanatos, but that so did creation. And I’ve been rereading a biography of Louise Bourgeois, who also talked about how you had to destroy to create in her famous work, The Destruction of the Father. I thought that [dress] was a really good example of that.

Jun Takahashi for Undercover, ensemble, fall 2020, Japan. Photo by Eileen Costa.

I found myself having a very different reaction to that dress than I did to the Viktor & Rolf one. Just because the Viktor & Rolf one didn’t look like an actual piece of clothing. It looked more like, something from a play, like a costume. Is it a deliberate choice to make something that is not wearable for most people?

Some designers use their runway looks as a way to clearly spell out the message of the collection. And then there’ll be other clothes, which may or may not even be on the runway, that you can buy that are wearable versions of it. Like in Second Skin, there is this big black outfit by Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons. The woman is completely hidden by this thing and it weighs a ton and nobody would wear that in real life. But it’s kind of symbolizing a thought on her part that clothes and body are in a strange relationship. And so the things on the runway will just be an exaggerated version of an idea she has for other clothes. Same with a lot of McQueen’s and a lot of John Galliano’s.

To what extent do you think that fashion designers have some actual knowledge of Freud and buy into it, and to what extent are they just sort of playing with stuff that’s in the zeitgeist?

I think on the whole, they just have the kind of general cultural awareness that any educated person has. Some will use terms like neurotic or projection, and you’ll have some who’ll know what a Freudian slip is. But I think what’s really important about psychoanalysis is this awareness that the unconscious could influence you without your being aware of it. And I think that’s what’s so interesting. You could have an emotion, and it’s your emotion, but you don’t really know why you have it or what’s happening with you.

You don’t need to convince artists that there’s an unconscious.

Published December 2025